Jody Weible keeps a jar on her front porch that she refuses to open, because the smell would make her eyes water and her throat close up. Inside is a goopy mixture of fermented corn seeds that she collected nearly four years ago from a field near her home in Mead, Nebraska, a town of about 600 people. The seeds had been applied to the soil as an “amendment” to boost fertility, but they were actually waste from a nearby ethanol plant, AltEn — waste that contained staggeringly high levels of toxic pesticides.

For nearly a decade, AltEn collected leftover seeds from around the country to use as the base for its ethanol, a corn-based fuel that’s mixed into gasoline. A byproduct was the fermented seed mixture, stored in a pastel-green pile that at one point took up 30 acres of the property. The smell it gave off was “acidic, rotten, dead,” Weible told Grist from her home less than a mile away from the plant. Residents kept their windows closed because of the stench; birds stopped coming to feeders. One woman said her dogs started having neurological problems after eating some of the waste.

The seeds AltEn used were coated with a class of chemicals known as neonicotinoids, or “neonics,” an insecticide that’s been linked to a nationwide pollinator decline and is under consideration for regulation by the Environmental Protection Agency. Residents of Mead suspected AltEn’s pesticide-laced byproduct was killing nearby bee colonies and polluting their water. State regulators finally shut the operation down in February 2021, and are now suing the company for allegedly violating the Nebraska Environmental Protection Act. But the shuttered site continues to pose a hazard to the community.

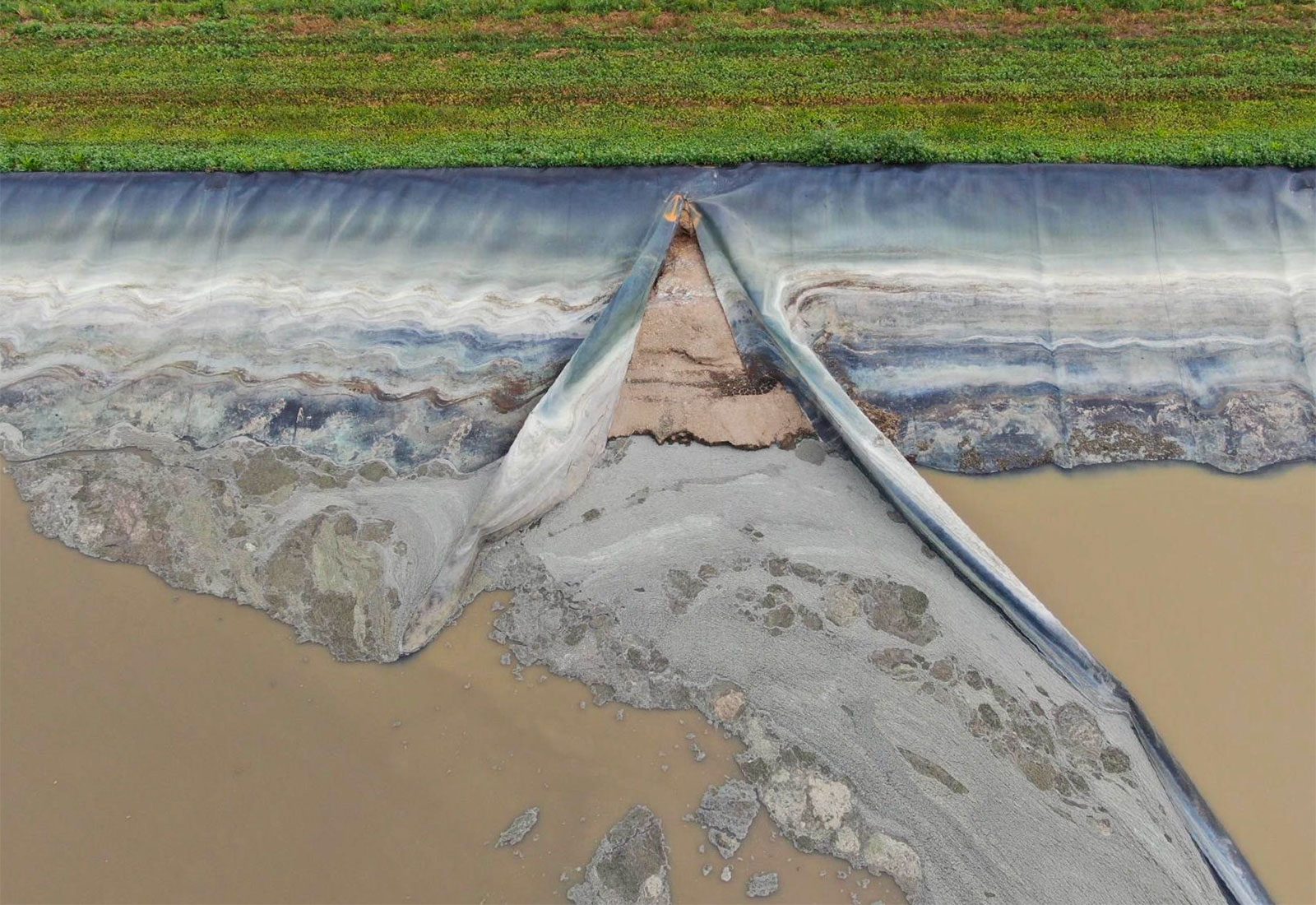

A few days after it closed, a frozen pipe ruptured at the plant, sending 4 million gallons of wastewater into local rivers and streams. Today, over a year later, pesticide-laden seed waste remains at the site. It’s been covered in a gray mixture of cement, clay, and polyester – an attempt to temporarily trap the toxic material while a longer-term solution is being developed. But researchers and environmental groups warn that the cleanup of AltEn is not happening quickly enough, and that neonics continue to leak into local streams and groundwater.

Experts said the situation in Mead should be seen as a wake-up call. It’s not clear how many of the country’s 210 ethanol refineries besides AltEn have utilized treated seeds; Nebraska’s lawsuit against the company mentioned one other plant, but didn’t identify it. But there’s not much preventing them from doing so — Nebraska is the only state to ban the practice, which it did just last year after the problems with AltEn came to light.

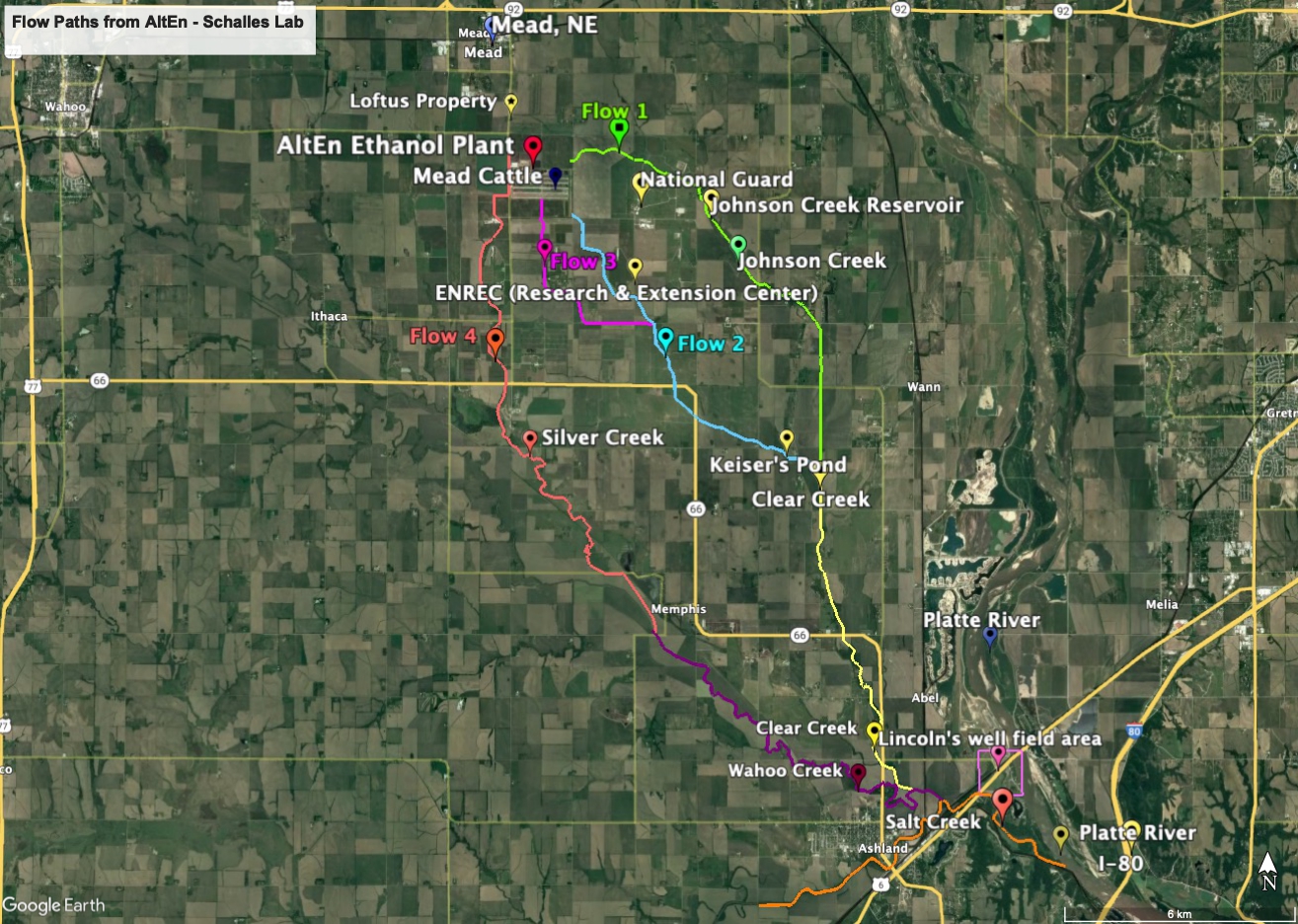

Environmental regulators last September detected neonics and fungicides 40 feet below ground at a drinking water well six miles downstream from the ethanol plant, according to the Lincoln Journal-Star. While the levels are still low and technically considered “safe” by the EPA, the results of the testing are far from comforting, warned John Schalles, a biologist at Creighton University in Omaha and member of a research group that’s monitoring the AltEn site. Rather, they are an indicator that the process of contamination is just beginning; toxins can take years to filter down through the soil and into the aquifer.

“In toxicology, the longer the exposure to anything like this, the worse it’s going to get,” Schalles told Grist. “We need to cut off the source of the exposure, which is all these waste products, both liquid and solids.”

For years, liquid waste was stored on the site in three lagoons. Testing by state regulators in 2019 detected neonics at over 5,000 times the level considered “safe” by the federal government. The Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality found concentrations of clothianidin at 58,400 parts per billion and thiamethoxam at 35,400 in one of the lagoons. To avoid harm to aquatic life, the U.S. EPA caps levels of these two neonics at 11 and 17.5 parts per billion, respectively. Inspections found multiple tears in the liners of at least two lagoons that “compromise[d] the integrity of the structure” and could have allowed the wastewater to seep into the ground, according to the state’s lawsuit against the company.

Residents like Weible are frustrated with the lack of accountability for AltEn, which racked up multiple environmental violations over the years but was allowed to continue operating.

“There’s no punishment,” Weible said. “They just get away with it. It’s disheartening, and it makes it hard to trust the [regulatory] process.”

The agricultural industry has enthusiastically embraced pesticide-treated seeds in recent decades. Seed producers apply chemical treatments, including neonics and fungicides, to the seeds they sell farmers, often before any pest issues are even detected. The sale of seeds treated with neonics tripled from 2004 to 2014, and more than 90 percent of all corn in the United States is grown with them. But as evidenced by the situation in Mead, this strategy has come at a cost, said Sarah Hoyle, a pesticide program specialist for the Xerces Society, a nonprofit focused on insect and other invertebrate conservation.

Because the chemicals are water-soluble, they’re known as “systemic” pollutants, Hoyle said, meaning they stay with the plant as it grows and then can be passed on to whichever organism comes into contact with it. That’s what makes them so dangerous for bees, as well as other insects and aquatic invertebrates. Neonics are also toxic to humans. Though research on their long-term effects is still ongoing, scientists know they target the nervous system, and they have been linked to birth defects, developmental delays in children, and even an increased risk of breast cancer. But despite these risks, the EPA doesn’t regulate treated seeds as pesticides because of an exemption for “treated articles” that doesn’t take into account how the chemicals stay in the plants as they grow.

What happened in Mead shows how the “mishandling of treated seed can result in pretty significant contamination that disrupts ecosystems and can put communities at risk,” Hoyle said. “We’re also seeing from this example how challenging it is to clean up these pesticides once they’re in the environment.”

AltEn’s plant in Mead opened in 2015 and produced approximately 24 million gallons of ethanol a year until its closure in 2021. For most of that time, it advertised itself as a recycling location for treated seeds. Agricultural giants such as Bayer and Syngenta sent AltEn their leftover seeds free of charge, which saved the companies money on disposal costs and gave AltEn free feedstock for its ethanol.

Production of the biofuel starts when corn or seeds are ground down and heated in water to break down the starch into sugar. The mixture is then left to ferment, further breaking down the sugars into ethanol, which is then distilled into a pure form that’s mixed with gasoline. That process leaves behind a solid mash of leftover corn and seeds, as well as liquid waste, all of which must be disposed of somehow.

The Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy, or NDEE, has maintained that it did not know AltEn was accepting seeds treated with pesticides, although the company made those plans clear in its initial permit application in 2012. Now, those chemicals are everywhere, entering Mead’s groundwater, streams, and soils. For years, AltEn left an 84,000-ton pile of fermented seed waste, known as “wet cake,” in an unlined waste pit on site. This would have allowed water-soluble neonics to leach into the soil and potentially reach the groundwater, Schalles said.

When it rained, runoff from the wet cake also likely transported pesticides and fungicides straight into local waterways, he added. Schalles’ research found four potential pathways from the AltEn site, all of which feed into the Platte River, a water source for numerous Nebraska cities, about 20 miles south of Mead. During dry spells, toxic dust could carry contaminants off of the pile through the air.

Up until 2019, the company also sold wet cake containing a whopping 427,000 parts per billion of clothianidin and 81,500 parts per billion of thiamethoxam to local farmers to apply directly to their fields to improve the quality of their soil, the state’s lawsuit alleges — about 85 times higher than the maximum amount allowed by law. AltEn also sprayed its own corn crops that it used for its ethanol production with the liquid waste, state regulators found, including for more than a year after officials told the company to stop.

Efforts to clean up the waste are starting to gain steam; contractors coated the wet cake pile with the hard cement, clay, and polyester covering, known as Posi-Shell, in late February to insulate it from stormwater and prevent gases from escaping. But the coating doesn’t address groundwater seepage. The cleanup campaign so far is also entirely voluntary, funded by the same companies that provided the seeds in the first place — with no funding from AltEn.

Requests for comment from AltEn and its lawyers went unanswered. The NDEE also declined to comment for this article, citing pending litigation. But the agency acknowledged in a January 24 letter to the seed companies, known as the AltEn Facility Response Group, that their cleanup plan isn’t a long-term solution.

“A compromised cover could lead to increased odors or generate potentially contaminated stormwater,” an NDEE official, Thomas Buell, said in the letter. The strategy also doesn’t include any information on how long the waste will remain at the site and how the group eventually plans to get rid of it, Buell wrote. NDEE’s director, Jim Macy, said during a public hearing in the state legislature on February 24 that he expects the group to submit a final remediation plan in the next few months.

To assess the extent of the contamination and its effects on the environment and human health, a team of researchers led by the University of Nebraska has been working to monitor the area since last spring. The group has been collecting soil and water samples, and is sending out surveys to local residents to learn about potential health impacts, according to Nebraska Public Media. But health issues resulting from neonicotinoid exposure could take decades to detect and treat, Schalles said, requiring continual funding from the state.

Receiving that support has been an uphill battle; in April, the Nebraska legislature approved a bill to supply the University of Nebraska researchers with $1 million, enough to fund the project for about a year. A previous bill to provide $10 million in funding failed in the Nebraska legislature last month.

Residents are also trying to hold state regulators accountable for allowing AltEn to pollute for so long, said Al Davis, a former state senator and lobbyist for the Sierra Club in Nebraska. He said the state was aware of the issues at the AltEn refinery for years but failed to impose penalties, potentially out of deference to the ethanol industry, a powerful player in Nebraska’s economy. On February 14, dozens of people attended a “Stop the AltEn Cover-up” rally at the state capitol and urged lawmakers to establish a special committee to investigate the causes and effects of the crisis.

Funding and transparency would be a good start, Davis said, though he believes federal aid and EPA oversight is also needed to deal with the scope of the contamination. Others have floated the possibility of the AltEn facility becoming a Superfund site, which would either force whichever company is found responsible for the contamination to pay for the cleanup, or give the EPA the funding and authority to do so.

“We’ve got a lot of great, intelligent, educated people here, but I don’t think we have the capability to address a problem this huge,” Davis said, calling the NDEE’s hesitation to penalize AltEn a “demonstrated lack of leadership.”

Residents like Weible are frustrated at the slow pace of change. The lawsuit filed last year by Nebraska’s attorney general Doug Peterson has dragged on without visible progress and the company has avoided paying penalties. She and others, including Davis, believe criminal charges against AltEn’s owners could be the only recourse left for Mead residents. Seed companies involved in the cleanup allege that AltEn has been selling its assets, according to a lawsuit they filed in February accusing the ethanol company of fraud. But Davis said the company likely doesn’t have the funds to remediate the area and pay for health monitoring even if the courts ordered it to.

In the meantime, coating the wet cake has temporarily stopped the odors. The EPA conducted air monitoring in September and didn’t detect any pollutants in amounts that would pose an “immediate health threat,” but Weible still fears that her community has been saddled with a legacy of contamination.

“We have people that have moved away,” she told Grist. “We have people that have come to live here and looked at places to buy or rent, and it was a particularly bad [air] day. And they went, ‘Oh, no, we don’t want to live here.’”