This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

“Is it green energy if it’s impacting cultural traditional sites?”

Yakama Nation Tribal Councilman Jeremy Takala sounded weary. For five years, tribal leaders and staff have been fighting a renewable energy development that could permanently destroy tribal cultural property. “This area, it’s irreplaceable.”

The privately owned land, outside Goldendale, Washington, is called Pushpum, or “mother of roots,” a first foods seed bank. The Yakama people have treaty-protected gathering rights there. One wind turbine-studded ridge, Juniper Point, is the proposed site of a pumped hydro storage facility. But to build it, Boston-based Rye Development would have to carve up Pushpum — and the Yakama Nation lacks a realistic way to stop it.

Back in October 2008, unbeknownst to Takala, Scott Tillman, CEO of Golden Northwest Aluminum Corporation, met with the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, a collection of governor-appointed representatives from Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana who maintain a 20-year regional energy plan prioritizing low economic and environmental tolls. Tillman, who owned a shuttered Lockheed Martin aluminum smelter near Goldendale, told the council about the contaminated site’s redevelopment potential, specifically for pumped hydro storage, which requires a steep incline like Juniper Point to move water through a turbine. Shortly thereafter, Klickitat County’s public utility department tried to implement Tillman’s plan, but hit a snag in the federal regulatory process. That’s when Rye Development stepped in.

“We’re committed to at least a $10 million portion of the cleanup of the former aluminum smelter,” said Erik Steimle, Rye’s vice president of project development, “an area that is essentially sitting there now that wouldn’t be cleaned up in that capacity without this project.”

Meanwhile, Tillman cleaned up and sold another smelting site, just across the Columbia River in The Dalles, Oregon, a Superfund site where Lockheed Martin had poisoned the groundwater with cyanide. He sold it to Google’s parent company, Alphabet, which operates water-guzzling data centers in The Dalles and plans to build more. For nine years, the county and Rye plotted the fate of Pushpum — without ever notifying the Yakama Nation.

The tribal government only learned of the development in December 2017, when the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued a public notice of acceptance for Rye’s preliminary permit application. Tribal officials had just 60 days to catch up on nine years of development planning and issue their initial concerns and objections as public comments.

When it came time for government-to-government consultation in August 2021, FERC designated Rye as its representative. But the Yakama Nation refused to consult with the corporation. “The tribe’s treaty was between the U.S. government and the tribe. We’re two sovereigns,” said Elaine Harvey, environmental coordinator at Yakama Nation Fisheries, who’s been heavily involved with the project. “We’re supposed to deal with the state.”

FERC countered that using corporate stand-ins for tribal consultation is standard practice for the commission. When the tribe objected, FERC said it could file more public comments to the docket instead of consulting.

But sensitive cultural information was involved, which, by Yakama tribal law, cannot be made public. Takala noted, for example, that Yakama people don’t want non-Natives harvesting and marketing first foods the way commercial pickers market huckleberries: “That has an impact for our people as well, trying to save up for the winter.” The tribe needs confidentiality to protect its cultural resources.

There’s just one catch: Rule 2201. According to FERC, Rule 2201 legally prohibits the agency from engaging in off-the-record communications in a contested proceeding. Records of all consultations must be made available to the public and other stakeholders, including prospective developers and county officials. Who wrote Rule 2201? FERC did.

“Nevertheless,” FERC wrote to the Yakama Nation in December 2021, “the Commission endeavors, to the extent authorized by law, to reduce procedural impediments to working directly and effectively with tribal governments.” FERC said the nation could either relay any sensitive information in a confidential file — though that information “must be shared with at least some participants in the proceeding” — or else keep it confidential by simply not sharing it at all, in which case FERC would proceed without taking it into account. So formal federal consultation still hasn’t happened. But FERC is moving forward anyway.

“It’s important for First Nations to be heard in this process,” said Steimle, the developer. During a two-hour tour of the site, he championed the project’s technical merits and its role in meeting state carbon goals. “If you look at Europe at this point, it’s probably 20 years ahead of us integrating large amounts of renewables.”

Steimle repeatedly described Rye as weighed down by stringent consultation and licensing processes. Rye, he said, lacks real authority: “We don’t have the power in the situation to ultimately decide, you know, it’s going to be this technology, or it’s going to be in this final location.” Becky Brun, Rye’s communications director, echoed Steimle’s tone of inevitability: “Regardless of what happens here with this pumped storage project, this land will most certainly get redeveloped into something.”

When asked what Rye could offer the Yakama people as compensation for the irreversible destruction of their cultural property, Steimle suggested “employment associated with the project.”

Takala wasn’t surprised. “That’s always the first thing offered on many of these projects. It’s all about money.”

Presented with the reality that Yakama people might not want Rye’s jobs, Steimle hesitated. “Yeah, I mean I, I can’t argue that — maybe it won’t be meaningful to them.”

But for Klickitat County, the jobs pitch works: It’s a chance to revive employment lost when the smelter closed. “That was one of the largest employers in Klickitat County — very good family-wage jobs for over a generation,” said Dave Sauter, a longtime county commissioner who finished his final term at the end of 2022. The smelter’s closing was “a huge blow,” he said. “Redevelopment of that site would be really beneficial.”

Sauter acknowledged the pumped hydro storage facility would only provide about a third of the jobs that the smelter offered in its final days, but “it will lead to other energy development in Klickitat County.” The county, with its armada of aging wind turbines and proximity to the hydroelectric grid, prides itself on being one of the greenest energy producers in the state and has asked FERC for an expedited timeline.

Klickitat County’s eagerness creates another barrier to the Yakama Nation. In Washington, a developer can take one of two permitting paths: through the state’s Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council, or through county channels. Both lead to FERC. In this case, working with the county benefits Rye: Klickitat, a majority Republican county, has a contentious relationship with the Yakama Nation, one that even Sauter described as “challenging.”

“Klickitat County refuses to work with us,” said Takala. On Sept. 19, 2022, Harvey logged into a Zoom meeting with the Klickitat County Planning Department to deliver comments as a private citizen. Harvey says county officials, who know her from her work with the Yakama Nation, locked her out of the Zoom room, even though the meeting was open to the public and a friend of hers confirmed that the call was working and the meeting underway. Undeterred, Harvey attended in person and delivered her comments.

The Planning Department denied that Harvey was deliberately locked out, claiming that everyone who arrived on Zoom was admitted. They also said they were having technical difficulties.

Fighting Rye’s proposal has required the efforts of tribal attorneys, archaeologists and government staffers from a number of departments. “Finding the staff to do site location is very difficult when we don’t have the funds put forth,” Takala said.

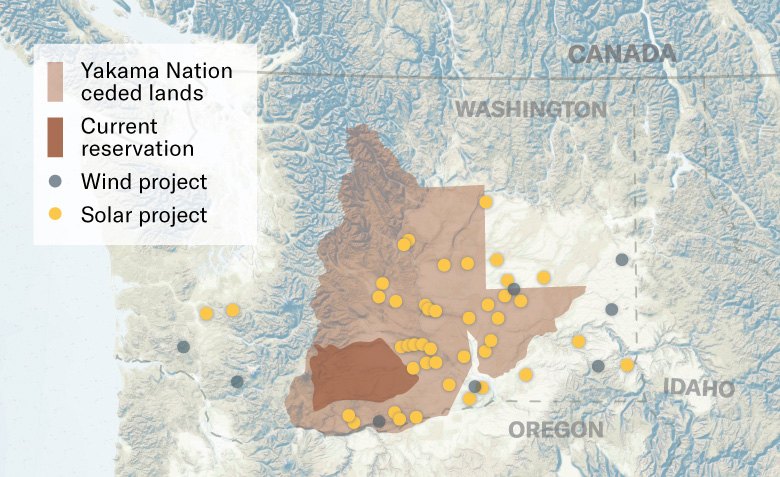

And Rye’s project is just one of dozens proposed within the Yakama Nation’s 10 million-acre treaty territory. Maps from the tribe and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife show that of the 51 wind and solar projects currently proposed statewide — not including geothermal or pumped hydro storage projects, which are also renewable energy developments — at least 34 are on or partially on the Yakama Nation’s ceded lands. Each of these proposals has its own constellation of developers, permitting agencies, government officials and landowners.

“There’s so many projects being proposed in the area that we here at the nation are feeling the pressure,” said Takala. He noted that when it comes to fulfilling obligations to tribes, the United States drags its feet. “But when it’s a developer, things get pushed through really quickly. It’s pretty much a repeating history all over again.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated to correct the map showing the proposed wind and solar projects in Washington. Originally, the solar and wind projects were inadvertently swapped.