In November, under a high sky in northwestern New Mexico, U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland stepped proudly to the podium against a backdrop of sandstone bluffs. She was flanked by Pueblo leaders who had gathered that day to commemorate the recently announced protections for Chaco Culture National Historical Park, where ancestral Puebloans created a sprawling center of trade and culture from the tawny-colored rock more than a thousand years ago.

“It is not difficult to imagine centuries ago children running around the open space, people moving in and out of doorways, bringing in their harvest or preparing food for seasons to come,” Haaland said of the Chaco complex, where multi-story ruins rise from the floor of a wide canyon. “We’re here because President Biden and I heard your voices and are taking important steps to take care of our land, our air, and our water.”

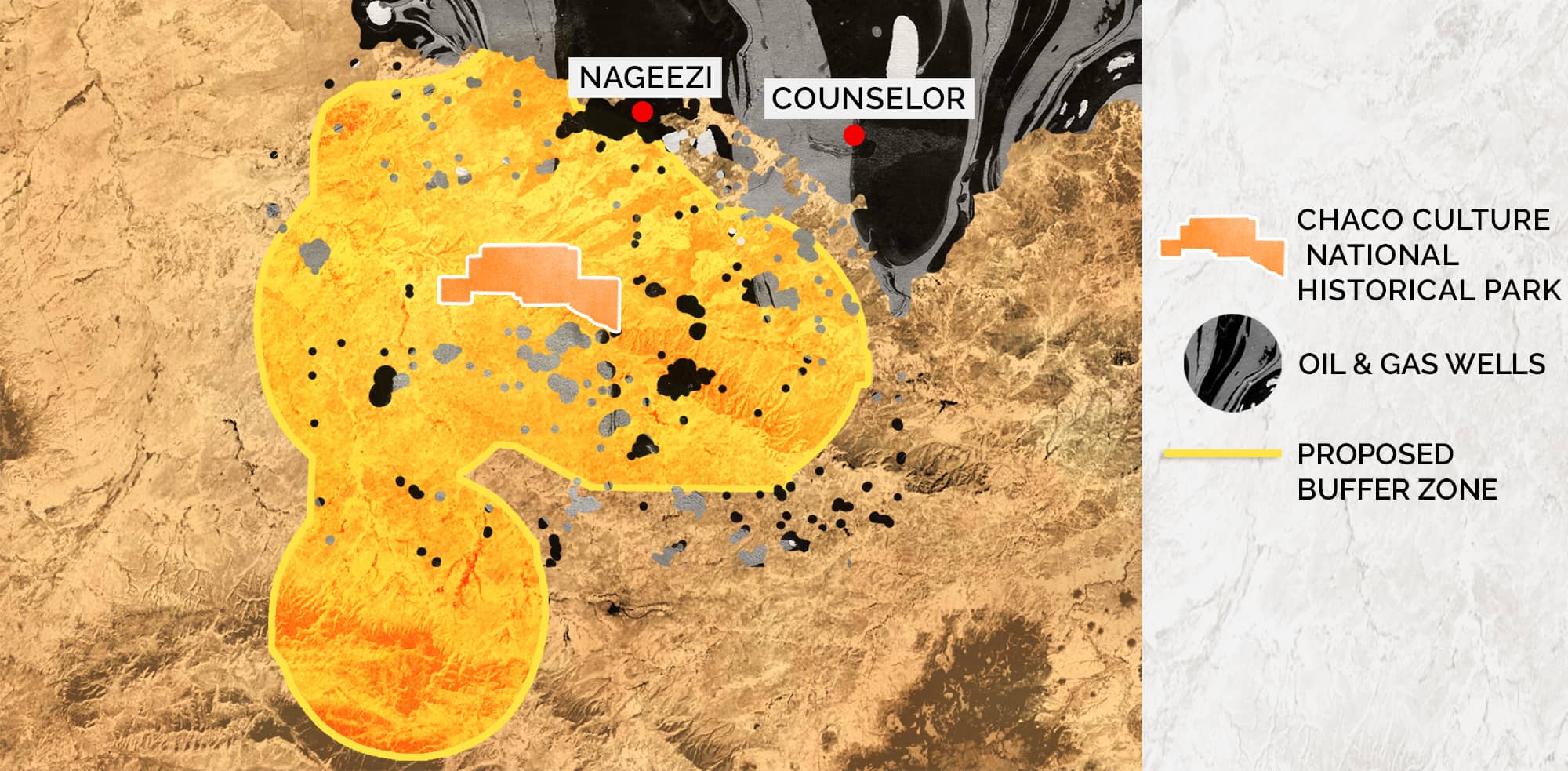

Haaland’s speech came days after the Department of Interior announced it was considering a 20-year moratorium on new federal oil and gas leasing within a roughly 10-mile radius around the park, an approximately 950,000-acre area referred to as the buffer zone. Along with shielding the site from fracking facilities that have encroached on the area in recent years, the action was touted as part of the Biden administration’s larger effort to curb greenhouse-gas emissions while promoting environmental justice and tribal consultation.

But a review of federal leasing data by Grist suggests that the protections are a superficial fix, as they will likely do little to impede the recent influx of oil and gas development. Although the federal government plans to prevent new leasing on hundreds of thousands of acres within the Chaco buffer zone, oil and gas companies with existing leases can continue to extract minerals within its boundaries.

According to data provided by the Bureau of Land Management, there are 310 active wells on 88 active federal leases covering nearly 100,000 acres within the buffer, and federal protections do nothing to stop the companies holding those leases from obtaining permits to drill more. That means that even under the agency’s plan, hundreds of new wells could be drilled in the area at any time in the future.

“There’s still going to be development going on in that 10-mile buffer, and there’s nothing to prohibit that,” said Carol Davis, director of Diné CARE, a Navajo-led environmental organization. Davis adds that the Interior’s moratorium could push drilling outside the buffer and into communities, “and that’s going to expose people to the adverse health impacts that are a result of oil and gas fracking.”

In fact, BLM is also considering a plan that could allow up to 3,100 new wells to be developed outside the buffer zone, adding to the roughly 21,000 active wells in the region.

Several miles east of the buffer, the BLM has also approved dozens of drilling permits near a series of mesas considered sacred by the Navajo Nation. Despite conducting an environmental review that projected one well per parcel, BLM has already approved at least 118 drilling permits on eight of those parcels, according to legal documents filed by Diné CARE.

“There is absolutely zero restraint from the Bureau of Land Management and the Biden administration at this point,” said Jeremy Nichols, climate and energy program director with WildEarth Guardians. “The mineral withdrawal is good politics — it’s good optics — but it’s not going to turn the tide because there are existing leases within the buffer, and outside the buffer it’s business as usual.”

A thousand years ago, Chaco Canyon was a bustling, central trade hub. The ancestral Puebloans built monumental “great houses” along the margins of the high-desert valley and conducted trade using an expansive network of roads. The largest of the ancient structures at the UNESCO World Heritage Site likely contained more than 600 rooms and took three centuries to complete. Chaco flourished between 850 and 1250 AD, before being abandoned.

Contemporary Pueblos are the descendants of the ancestral Puebloans that built Chaco, and although they no longer inhabit the same area, many Pueblo people retain a cultural and spiritual connection to the sandstone structures and other sites dispersed throughout the region. The outlying areas are now home to Navajo families who reside either on the sparsely populated plateau, or in the tiny towns that dot the landscape, like Nageezi, Counselor, and Ojo Encino.

In the 1920s, natural gas deposits were discovered in the basin, and by the early 2000s, fossil fuel extraction occurred throughout the region. Then, around 2010, with the advent of new hydraulic fracturing methods, such as horizontal drilling, fracking began in earnest in the southern part of the basin, near the Chaco ruins, where companies tapped into oil and gas deposits that were difficult to access using vertical drilling techniques.

Many of those new wells were concentrated on public lands managed by the BLM, which owns a large portion of land surrounding Chaco Canyon, along the eastern edge of the Navajo Nation. Ownership of lands in the area is often referred to as a “checkerboard” of federal, state, private and tribal lands. Some of those tracts are also so-called “Indian allotments,” lands which the federal government distributed to individuals and families as a way to break up reservations and assimilate Indigenous people by making them landowners. Between 2014 and 2019 alone, the BLM approved more than 350 drilling permits in the greater Chaco region.

In the mostly Navajo communities that make up the area, the drilling boom resulted in wells that are in some places a few hundred feet from homes. A cluster of wells releases toxic emissions less than 2,000 feet from the Lybrook Elementary School, where an almost entirely Native American student population is exposed to a rotten-egg odor of hydrogen sulfide, a byproduct of the frequent flaring that occurs when excess gas is burned off to avoid methane emissions.

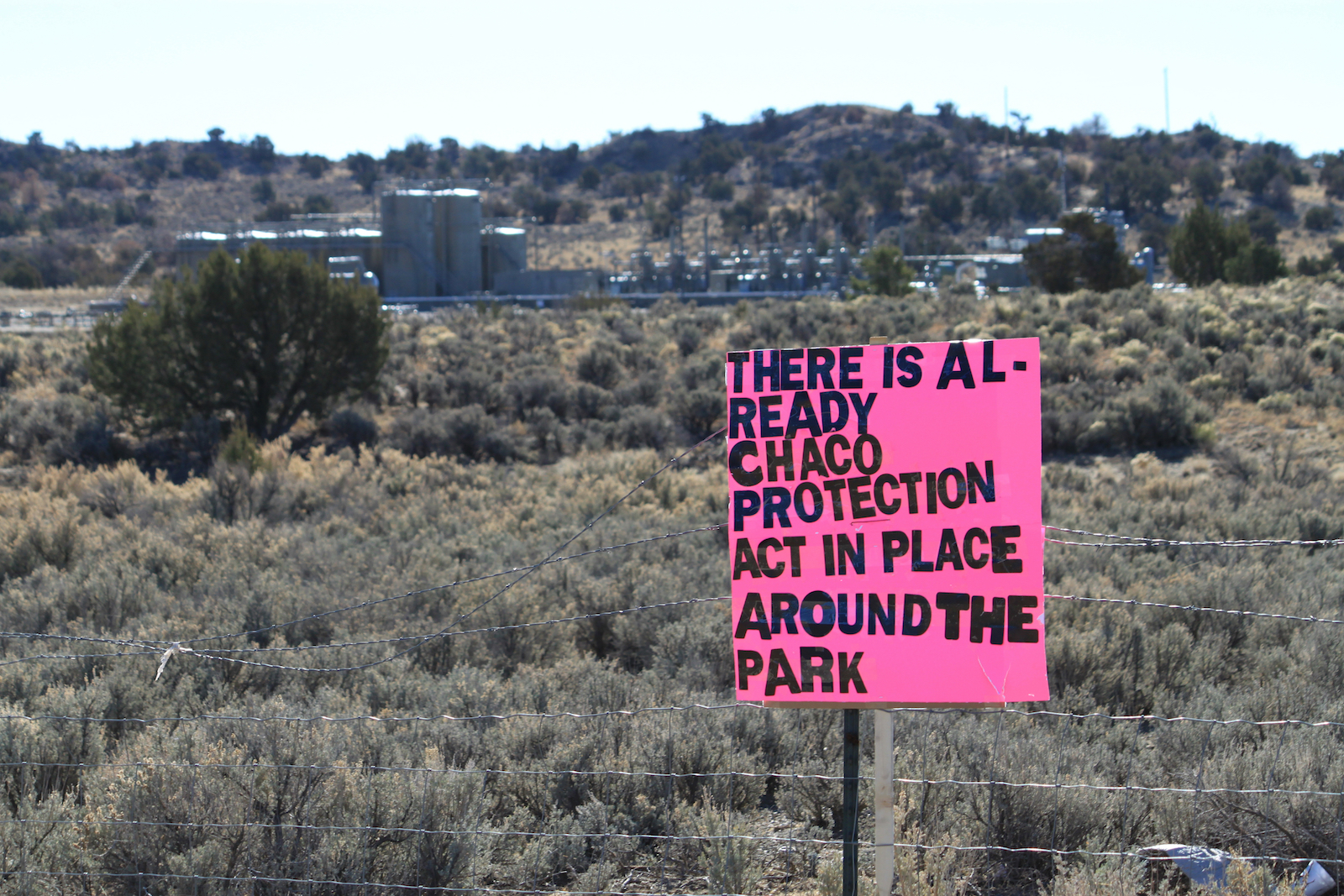

In 2019, New Mexico legislators, including then-U.S. Representative Haaland, introduced the Chaco Cultural Heritage Area Protection Act, which would have banned oil and gas leasing within a buffer zone permanently. The bill passed the House but died in the Republican-controlled Senate. Once Haaland was appointed Secretary of Interior, she took matters into her own hands, crafting the 20-year withdrawal proposal, which went into effect in January.

But companies currently operating within the buffer could still obtain permits to drill one, or multiple, wells on a given parcel. Based on the average number of wells on each active, federal lease in northwestern New Mexico, the existing leases inside the buffer could see more than 200 additional wells in the future. And that potential well count excludes the development that could occur on the much smaller portion of land within the buffer consisting of state and private land, as well as Indian allotments.

Because Indian allottees can lease their lands to oil and gas companies for royalty payments, the Chaco proposal became a point of contention in the region. Many Navajo allottees were concerned that the leasing ban would affect their royalty payments or eliminate their ability to lease out their lands, leading to opposition that ultimately resulted in the Navajo Nation withdrawing from the proposal after initially signaling support. According to the BLM, the withdrawal will not affect the ability of allottees to lease their land for oil and gas interests.

“We are not a monolith, and there were dissenting voices among allottees,” said Mario Atencio, a member of Diné CARE whose family owns an allotment just outside the buffer. He added that the most vocal opponents “claimed to represent allottees, but they don’t represent me.”

In the past year, Diné CARE and WildEarth Guardians have filed multiple legal challenges against the BLM for its approval of hundreds of lease sales and drilling permits in the greater Chaco region, including more than 100 permits issued to EOG Resources, a former Enron affiliate that amassed 40 parcels covering 45,000 acres of public land under the Trump administration.

“Right now, they’re bulldozing a road in a very sacred place,” Atencio said. He added that the lack of tribal consultation “feels no different than the Trump administration.”

Among the groups’ concerns is that BLM’s Farmington Field Office continues to allow drilling based on an outdated resource management plan, a document that forecasts the pace and scale of future oil and gas development. Because the plan was created in 2003 — before the advent of horizontal drilling — the groups argue that BLM has had no way of analyzing the “increased risks and impacts” of the new drilling technologies.

A proposed amendment to the plan estimates that between 2,300 and 3,100 new wells could be developed in the area over the next 20 years.

“That’s not a cap on what [BLM] can approve. That’s just what their best guess is,” said Kyle Tisdel, an attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center. “And the problem is that they’re just doing whatever industry says that industry wants to do.”

When the Interior Department announced the 10-mile buffer around Chaco in November, Haaland emphasized that the withdrawal would coincide with an “honoring Chaco” process that would include formal consultations with tribes and a series of ethnographic studies exploring the area’s cultural history. Pledges to engage in meaningful tribal consultation are often met with distrust in Indigenous communities given the federal government’s horrendous track record when it comes to considering human rights and tribal sovereignty. But the historic appointment of Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo, gave many Indigenous people hope that their voices would finally be heard.

Julia Bernal, director of Pueblo Action Alliance, spent the past five years fighting for federal protections against fracking in the Chaco region. And while Bernal believes more should be done to protect the environment and public health in the area, she said the Interior Department’s stated commitment to incorporating Indigenous knowledge and studies is “unprecedented,” and a credit to Haaland’s investment in the issue.

“Based on my own conversations with [Haaland], it’s not like she has the ability to implement extreme change even though she’s in this position,” Bernal said. “It’s always hard to convey why land and water and air are culturally and spiritually important, and not just for economic gain.”