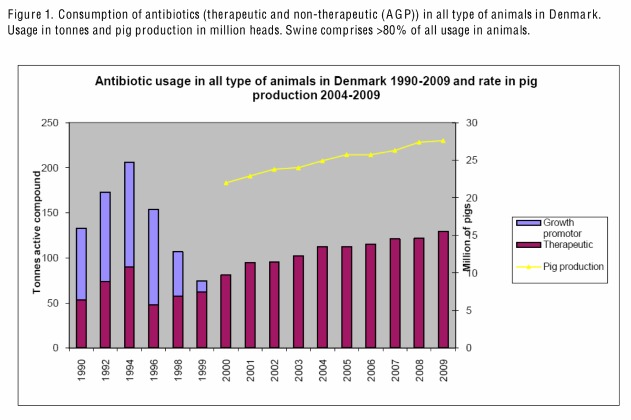

The editors of Scientific American recently encouraged U.S. hog farmers to “follow Denmark and stop giving farm animals low-dose antibiotics.” Sixteen years ago, in order to reduce the threat of increased development of antibiotic resistant bacteria in their food system and the environment, Denmark phased in an antibiotic growth promotant ban in food animal production. Guess what? According to Denmark’s Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries the ban is working and the industry has continued to thrive. The government agency found that Danish livestock and poultry farmers used 37 percent less antibiotics in 2009 than in 1994, leading to overall reductions of antimicrobial resistance countrywide.

Except for a few early hiccups regarding the methods used in weaning piglets, production levels of livestock and poultry have either stayed the same or increased. So how did Danish producers make this transition, and why isn’t the U.S. jumping to follow suit? Like many things in industrial agriculture, the answer is not clear.

If any country knows how to intensively produce food animals, particularly pigs, it is Denmark. In 2008, farmers produced about 27 million hogs. In fact, the Scandinavian country claims to be the world’s largest exporter [PDF] of pork. Thus Scientific American editors argue that the Danish pork production system should serve as a suitable model to compare to ours. U.S. agriculture economists from Iowa State University agree. In a 2003 report, Drs. Helen Jensen and Dermot Hayes stated that Denmark’s pork industry is ” … at least as sophisticated as that of the United States … and is therefore a suitable market for evaluating a ban on antibiotic growth promotants (AGPs).”

Based on Denmark’s experience, concerns that an AGP ban in the U.S. would cripple the industry appear to be overblown. A study published last year in the American Journal of Veterinary Medicine by Danish researchers suggested that Denmark’s AGP ban in food animals reduced overall antibiotic use and did not significantly impact production. In fact, recent numbers from Denmark show production levels of hogs increased by roughly 50 percent between 1992 and 2008.

So what additional changes did Danish hog producers make in their methods of production to ensure that the AGP ban did not negatively affect their bottom line to a significant degree? Robert Martin, senior officer of the Pew Environment Group and former executive director of the Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production, visited several Danish hog farms in 2009 to see first hand what producers were doing to compensate for not being able to use antibiotics as growth promoters. Martin listed some of what he describes as the most important changes:

- Switching to lower density models of housing pigs

- The use of open pen and deep bedding systems

- Cleaning barns more frequently and systematically

- Improved ventilation systems

- Improved quality of feed

- Extending weaning period for piglets

Martin explains that many of these changes were phased in as farmers adopted a set of new best practices. Martin says immediately following the ban, Danish producers did see an increase in mortality of young pigs. “But instead of reverting to using antibiotics as a crutch,” Martin continued, “they initiated changes in their system.” For example, Martin learned that many producers extended the piglet weaning times by about 10 days, allowing maternal antibodies in milk to provide increased immunity. Martin also pointed out that reducing the crowded conditions and switching to a dry, deep bedding system, “allowed them to manage waste more effectively.” He said the changes are also “more humane for the pigs.” Moreover, Martin says, “They also paid more attention to feed mixtures instead of relying on antibiotics for weight gain.”

Dr. Jensen and Hayes’s report, published in the Iowa Ag Review, determined a ban similar to Denmark’s could cost the U.S. industry more than $700 million over 10 years and increase the price of pork by about 2 percent at the grocery store. Hayes noted, in recent email exchanges with the Center for a Livable Future, that in the long run a ban would not keep producers from making money. He also wrote, “hog farmers would reduce production until prices recovered, so there is no profit impact.” When it comes to the study’s findings, Hayes believes the economics are secondary:

The key take away for me from our studies was that the ban at the finishing stage worked as planned and reduced antibiotic use by a lot. However, when they extended the ban to the weaning state they ended up using more antibiotics and these were stronger human-use antibiotics. So a ban at the weaning stage did not work in terms of its original intent.

It is worth noting that recent Denmark data shows weaner mortality is significantly lower since the ISU study was published in 2003. Despite that fact, Hayes is correct. The therapeutic use of antibiotics has increased since the ban was instituted. According to the latest Danish Integrated Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring and Research Program (DANMAP) report [PDF], therapeutic antibiotic use rose by almost 13 percent from 2008 to 2009. DANMAP also found the occurrence of resistance in Danish pork increased during that time period, “and is not significantly lower than in imported pork.” However, resistance to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin, an important antibiotic in human medicine, was very low in E. coli from Danish pork in contrast to imported pork. It is important to point out that therapeutic use poses much less antibiotic resistance risk than low-dose application. Don’t forget, Denmark’s overall antibiotic use in all food animal production remains nearly 40 percent lower then when the ban was first initiated.

If the AGP ban is, at the very least, reducing overall antibiotic use and Danish pork production levels are increasing, why wouldn’t U.S. producers follow suit? The National Pork Producers Council (NPPC) lobbyists publicly maintain they still don’t believe antibiotic use in food animals poses a risk to human health. In a presentation [PDF] prepared for the World Pork Expo 2010, Chelsea Redalen, the NPPC’s director of government relations, maintained that there is “little to no evidence that restricting or eliminating the use of antimicrobials in food-producing animals would improve human health or reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance to humans.”

Statements like these, repeatedly made by hog industry representatives, leave many public health experts exasperated. Numerous peer reviewed research studies [PDF], including in the U.S. and the Netherlands, clearly demonstrate the transmission of antibiotic resistant bacteria from food animals to people. Studies out of the Netherlands published in the Journal of Emerging Infectious Diseases and the Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials, demonstrate that MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) was transmitted from pigs to a farmer, and between pig farmers and their family.

Despite industry claims, U.S. government health officials have concluded there are direct links between antibiotic use in food animal production and the risk of antibiotic resistant infections in people. Responding to a letter from Drs. Robert Lawrence and Keeve Nachman of the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future (CLF), the director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Thomas Frieden, confirmed that the CDC, “feels there is strong scientific evidence of a link between antibiotic use in food animals and antibiotic resistance in humans.”

CLF helped bring to light recently released FDA data showing that 80 percent of the antibiotics produced for human and animal use in the U.S. are sold for use in food animals. Even if significant portions of those antibiotics are used to treat disease, Dr. David Love, CLF scientist, says he finds that statistic, “astounding.” Love believes, “if producers are reliant on the use of antibiotics to produce animals in a highly concentrated way, it means that the design of these farms makes them breeding grounds for diseases.” “Even more troubling to me,” Love says, “is the unwise use of antibiotics for growth promotion in animal production, which compromises antibiotics, a precious resource used to protect the public’s health.”

Curently there is proposed federal legislation that would greatly limit antibiotic use in U.S. food animal production. Rep. Louise Slaughter (D-N.Y.) recently reintroduced the Preservation of Antibiotics for Medical Treatment Act, better known as PAMTA. The bill would ban the routine use of antibiotics “deemed” critical in human medicine to promote growth in healthy animals.

So, should the U.S. follow Denmark’s lead and stop all food animal producers from dishing out low dose-antibiotics? Public health experts say it appears that those with a higher priority on limiting health risks are at loggerheads with those unwilling to change or corporations more concerned about the risks of increased costs. One thing is clear — most large pork producers do not plan on instituting a ban voluntarily.