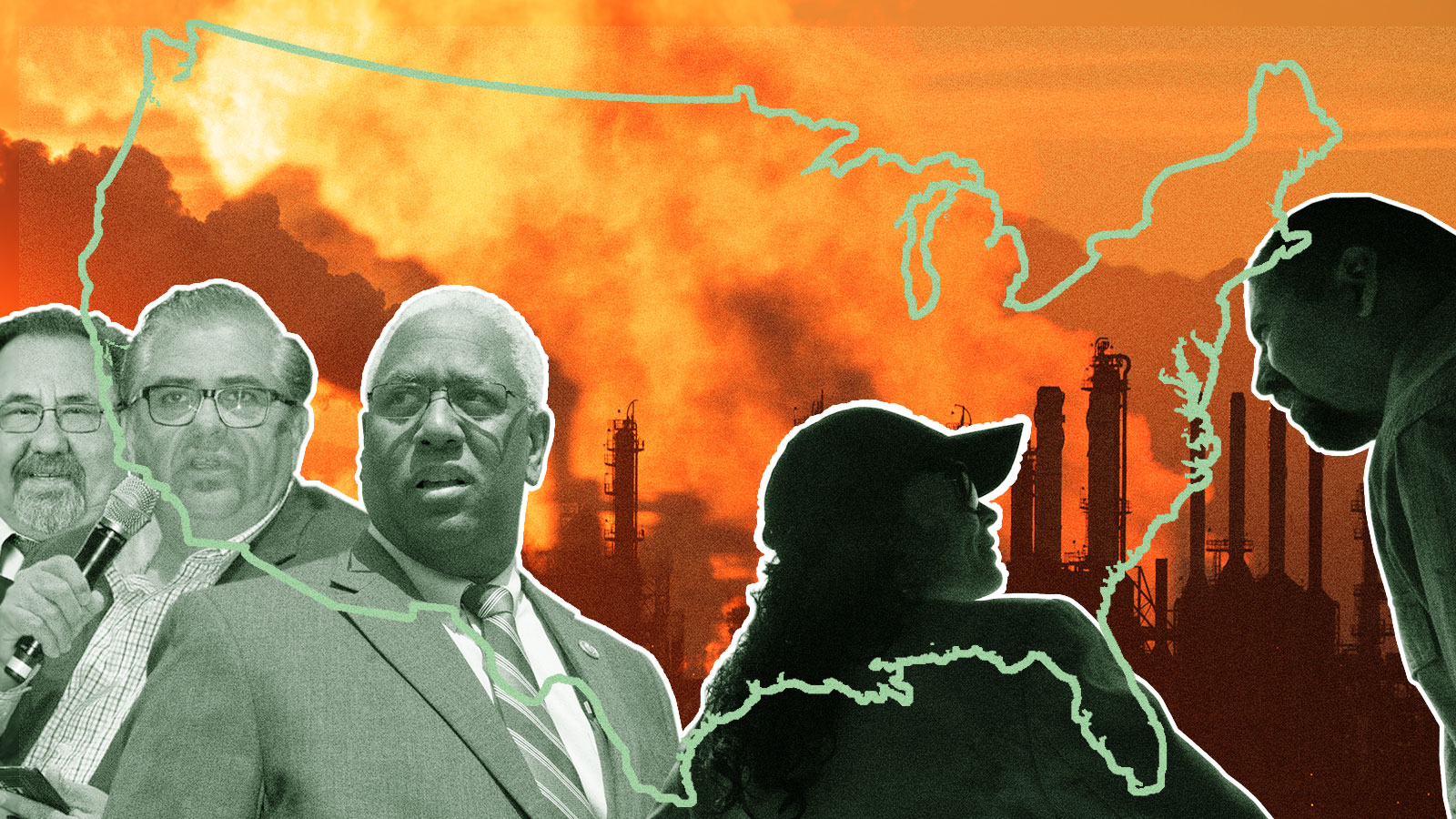

When Democratic U.S. Representatives Raúl M. Grijalva and A. Donald McEachin brought environmental justice advocates to Washington, D.C. last year to help craft the Environmental Justice for All Act, the plan was that, from start to finish, the bill would engage the people most affected by exposure to environmental toxins, pollution, and contamination.

So last month, after the 130-page draft bill was introduced, community advocates championed continuing this same approach through a national tour where grassroots organizations and frontline communities would have a chance to have their say on the bill. Now, the novel coronavirus pandemic has upended those plans. With millions across the country taking shelter in their homes, the bill’s supporters say they will forge ahead, albeit with altered plans, to bring the bill to communities across America under a new virtual reality.

McEachin, one of the bill’s authors, told Grist last week that, although the months ahead will be tough, Americans will survive the pandemic. But unless the climate crisis is addressed, he added, humankind “as we know it” won’t survive past 2050.

“That’s why it’s so important that we keep environmental justice issues and climate crisis issues at the forefront of every discussion that we’re involved in, no matter what the crisis of the day might be, because these crises pale in comparison to the deadline that we face in 2050,” said McEachin.

On Thursday, Grijalva and McEachin penned a letter to House and Senate leaders in both parties, emphasizing this point and urging them to incorporate environmental justice measures into any upcoming stimulus legislation. The provisions they would like to see include: funding to immediately provide potable water and sanitation systems to homes lacking safe drinking water, the expansion of programs that help households lower energy bills and make energy efficiency improvements, and the prioritization of federal programs that reduce diesel emissions. The letter was co-signed by 43 additional House Democrats.

The Environmental Justice for All Act, though unlikely to pass Congress in the near future, is the centerpiece of the lawmakers’ ongoing efforts to elevate environmental justice in federal policy. Grijalva and McEachin worked on the bill throughout the last year with the help of an alliance of stakeholders — including representatives from grassroots organizations that focus on everything from climate justice to industrial pollution — known as the Environmental Justice Working Group.

Members of this group convened advocates and gathered public input and online comments to produce the final bill. Now this same team is using that experience to chart a virtual path forward so that the legislators can receive community feedback. They must determine how to overcome the digital divide in communities where low-income residents have limited or no access to the internet or cell phone service. The challenge, said McEachin, is for those who are part of the climate change and environmental justice movement to stay focused, maintain momentum, and remind Americans that the deadline is looming.

“2050 is off in what some people might feel is the distant future,” said McEachin. “It is coming as sure as the sun is rising every day, and we’ve got to make sure that we’re addressing these climate issues and these environmental justice issues each and every day.”

José Bravo, a member of the bill’s working group, said the original plan was for a tour that would help the lawmakers experience what communities are facing around the country, whether it’s water pollution or chemical exposure. The ultimate goal is to help legislators prioritize issues based on direct community input. Bravo said his primary concern moving forward is ensuring that even those low-income communities that have limited or no digital connectivity remain part of the discussion.

“I would support [a virtual tour] in these uncertain times, but there has to be a plan on having proper representation from the community,” said Bravo, who is the executive director of the San Diego-based Just Transition Alliance, a national coalition of environmental justice organizations and labor unions.

The Environmental Justice for All Act seeks to:

- Amend the Civil Rights Act to allow private citizens and organizations that experience discrimination (based on race or national origin) to seek legal remedies when a program, policy, or practice causes a disparate impact.

- Provide $75 million annually for research and program development grants to reduce health disparities and improve public health in disadvantaged communities.

- Levy new fees on oil, gas, and coal companies to create a Federal Energy Transition Economic Development Assistance Fund, which would support workers and communities transitioning away from greenhouse gas-dependent jobs.

- Require federal agencies to consider health effects that might accumulate over time when making permitting decisions under the federal Clean Air and Clean Water acts.

The stakeholders also intend to codify and make enforceable a long-standing executive order on environmental justice that then-President Bill Clinton signed in 1994. The order requires federal agencies to address environmental justice, but, according to Bravo, for too long agencies have not followed through. He said that the agencies should create plans showing how they intend to incorporate environmental justice when carrying out their respective missions.

“It’s been over 25 years, and we still don’t have those plans,” said Bravo. “Ultimately, what we’re saying is that everybody deserves the right — and has the civil right, the human right, the unalienable right — to live in a toxic-free environment.”

The bill also strengthens and updates the landmark National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) at a time when the Trump administration is pushing to overhaul the 50-year-old law and eliminate protections that vulnerable communities across the country have long tapped to address environmental health concerns. NEPA currently requires that federal agencies assess the environmental effects of proposed actions such as federal infrastructure projects. The new bill would include additional protections, like a consideration of cumulative exposure effects in community impact reports.

Policy analyst Anthony Rogers-Wright represented the Climate Justice Alliance, which works with frontline communities to develop a transition to clean energy policies and equitable economies, during the bill drafting process. He described the inclusive approach to developing the bill as the gold standard for future work — and he contrasted it with the way the Green New Deal congressional resolution was developed.

“Frontline communities were at the table from the onset. From the beginning it was a transparent process. People were speaking for themselves,” said Rogers-Wright, who is also a 2016 member of the Grist 50. “It’s not just the policy — it’s also the process of getting to that policy.”

The legislation incorporates feedback from hundreds of activists and environmental justice movement leaders across the country. It has also been endorsed by a broad range of advocacy organizations with a similar geographic reach.

The bill’s ultimate chances of becoming law are still unknown, given the pandemic crisis and unknown outcome of the 2020 election.

“Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic is wreaking havoc, and EJ communities are extremely vulnerable making the EJ for All bill even that much more important,” Angelo Logan, another member of the working group and the campaign director of the national Moving Forward Network, wrote in an email. (The Los Angeles-based organization works to protect disadvantaged communities from the adverse effects of the global freight transportation system.)

In communities like Claymont, Delaware, the passage of a federal environmental justice act could be critical.

Local and state laws don’t do enough to protect residents from industries that pollute residential neighborhoods, said Clayton resident Larry Lambert, a member of the Delaware Concerned Residents for Environmental Justice. Tired of trying to fix these issues from the outside, Lambert decided to run for the state house of representatives. But in the meantime, he’s placed his hopes on the passage of the Environmental Justice for All Act.

“This bill is the beginning,” said Lambert. “We know there is no such thing as a silver bullet, but we have to start somewhere.”