This post has been updated to include a comment from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, which was received after publication.

On a spring weekend morning a few weeks ago, Judy Kelly stepped outside of her house in Broomfield, Colorado, to grab the newspaper when her nose perked up. It smelled like something was burning.

Kelly, who’s 73, lives in an upscale, 55-and-up retirement community called Anthem Ranch, which sits below the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. The 1,300-home development is manicured and quiet, with green lawns and landscaped roads that flower out into smaller cul-de-sacs. Its active residents enjoy their own private fitness center, pool, movie theater, and more than 90 clubs that meet in a central community center. But about a quarter of a mile away from the southern border of this retirement dreamland sits a circle of fortress-like walls that enclose the Livingston fracking site, which contains 18 wells owned by Extraction Oil and Gas.

Kelly is among more than 200 Broomfield residents who have submitted complaints to the city since November, reporting chemical smells and symptoms like headaches, burning eyes, and nosebleeds that they believe are caused by oil and gas activity in the area.

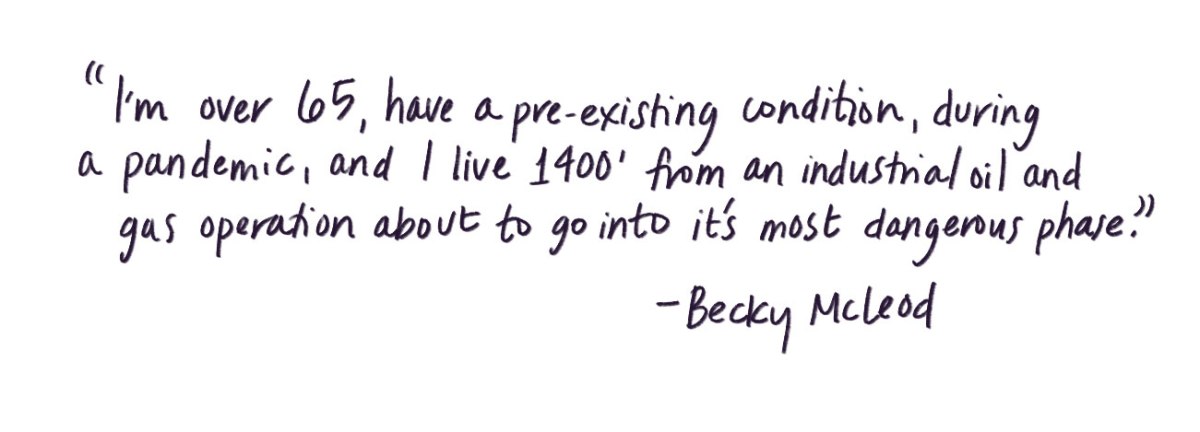

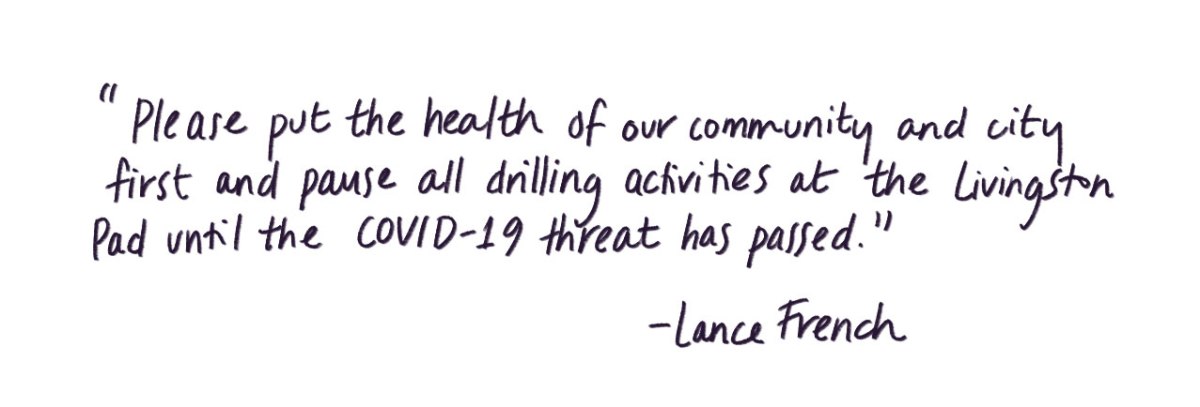

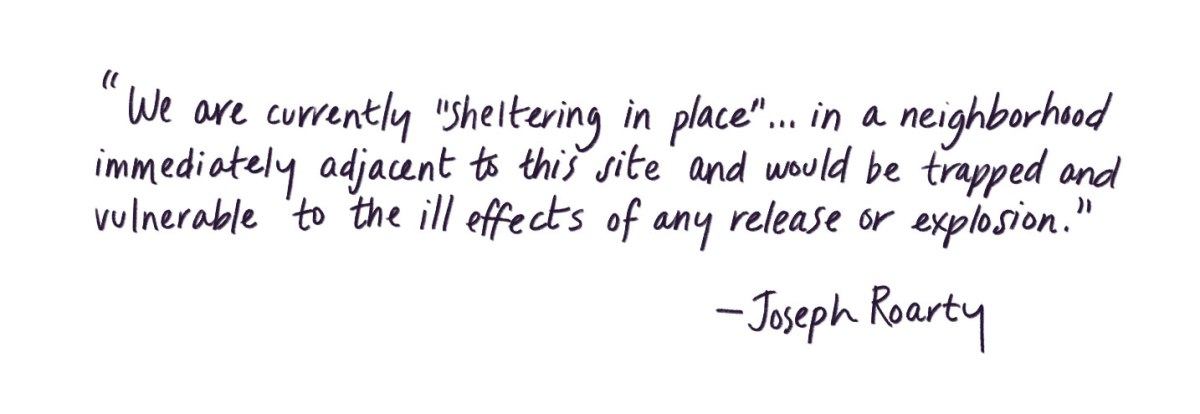

An excerpt from an email sent to the city by a resident concerned about the Livingston fracking site.

When she notified the city about the smell that morning, she was told that a city inspector had been on the site already and nothing was wrong. But Kelly was on high alert. Just a few days earlier, Extraction had begun “flowback,” a part of the fracking process that is associated with some of the highest emission rates of carcinogenic chemicals like benzene. Even under normal circumstances, flowback scared Kelly, who had followed the devastation in neighboring Weld County when one of Extraction’s wells exploded during the process in 2017, causing a major fire and injuring a worker. Kelly and her husband, who has pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, a lung disease, had planned on leaving town to stay with their son when flowback at Livingston began.

The COVID-19 pandemic threw a wrench in those plans. On March 25, when Colorado Governor Jared Polis issued a statewide stay-at-home order to stop the coronavirus’s spread, Kelly and her neighbors were suddenly trapped, trying to avoid one health hazard while worrying about being exposed to another. After all, fracking remained a “critical” business, according to the state.

“Where am I going to go?” Kelly asked. “I can’t go to a hotel. I can’t risk that with my husband. I have nowhere to go now.”

Judy Kelly and her husband wear masks near the fracking site next to their home in Broomfield, Colorado. Courtesy of Judy Kelly

Kelly’s dilemma is not unique. Across the country, millions of people live within half a mile of fracking sites and other oil and gas activity and are exposed to a slew of toxic chemicals in their day-to-day lives. Researchers have found that those living close to fracking are more likely to suffer from cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses — the very underlying conditions that make them more vulnerable to the most severe outcomes from COVID-19. While many residents may have found ways to seek respite from these toxic emissions during normal times — whether it was working or going to school elsewhere, or simply moving in with friends and family during the most intense periods of activity — those options went out the window when state governors began announcing stay-at-home orders.

For its part, Extraction says that Anthem Ranch residents have nothing to worry about. The company did not respond to Grist’s detailed list of questions, but in legal filings and public testimony it has stated that the new technology it uses for flowback has been shown to keep emissions far below the levels associated with traditional techniques. In a complaint filed in a Colorado court, the company’s lawyers said that the “anxiety and stress” experienced by Broomfield residents was “self-induced.”

Broomfield vs. Extraction

The unsettling bind that the stay-at-home order put many residents in was not lost on Laurie Anderson, a Broomfield city councilwoman who lives just half a mile from the fracking site in another neighborhood called Anthem Highlands. The night Governor Polis’ order came down, a special meeting of the city council was scheduled to discuss the potential dangers of work continuing at the Livingston site during the pandemic. The council decided to draft a proposal ordering Extraction to postpone flowback — a process where the chemical-laden water used to fracture open the shale flows back to the surface and must be collected, treated, and disposed of — until the stay-at-home order was lifted.

“The thought was to protect these residents, to delay flowback, understanding that it has to happen because they’ve already fracked these wells,” said Anderson, who is also an organizer for Moms Clean Air Force, a national advocacy group that fights polluters. “It was only going to delay them for a couple weeks.”

Of particular concern was Anthem Ranch, where the median age is 70 years old. The city’s public health staff drafted up an order and included data showing that people over 65 are more susceptible to COVID-19 complications, that the top symptom reported by older Broomfield residents in the city’s oil and gas complaint system was “anxiety/stress,” and that stress and anxiety are linked to poor health outcomes in general.

Anthem Ranch is an upscale retirement community in Broomfield, Colorado. The 1300-home development sits about a quarter-mile from a fracking site. Courtesy of Judy Kelly

But two days later, before the council could discuss the draft proposal, Extraction headed them off at the pass. The company secured a temporary restraining order from the Seventeenth Judicial District Court in Colorado, which prohibited the city from halting or delaying its operations. According to court documents, Extraction alleged that the city was acting in bad faith, trying to “shut down Extraction’s operations not because they pose any real health risk, but because they are unpopular.” Then, on March 30, the company filed an official complaint with the district court against the city, seeking damages for a breach of contract.

It’s true that this was far from the first time Broomfield had tried to interfere with Extraction’s … extraction. The city has battled the company at every stage of the drilling process in response to complaints from residents about odors, health symptoms, and noise.

An excerpt from an email sent to the city by a resident concerned about the Livingston fracking site.

Several times the city has contacted the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC), a state regulatory body, to address those complaints. According to Megan Castle, a COGCC spokesperson, the agency intervened once in response to a noise issue and a second time to request the company swap drilling fluids which were causing odor complaints. Castle said the agency has conducted additional noise monitoring and did not find that the site was out of compliance with state regulations.

Andrew Bare, a spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, said that the nature of some of the complaints — such as odors that would likely have dissipated by the time inspectors reached the site — made taking action against Extraction “difficult.” Bare said that the agency sent a mobile air monitoring lab to the site in response to residents’ concerns and that the lab will remain near the Livingston site for at least another two weeks.

In legal documents, Extraction claims it has gone above and beyond the best management practices required by its operating agreement with the city, including investing more than $250 million on a “Next Generation Flowback” system to reduce emissions during the two to three months flowback is expected to last. At the public meeting last month, representatives from the company explained to the council that instead of storing and processing the flowback fluid on site, the company would ship it via pipeline to a facility in Weld County. They asserted that the design eliminates “99.9 percent of emissions” and significantly reduces the duration of the flowback phase. Later at the meeting, Barbara Ganong, a petroleum engineer who was hired by the city as a consultant, asserted that Extraction’s decision to pipe fracking fluids offsite represented a “paradigm shift.”

Air quality experts hired by the city gave a presentation showing that without this new closed system, emissions during flowback could have been 31 times higher than during fracking. Still, when they measured emissions during flowback at another Extraction well in a less populated part of town, they said emissions were still double those during fracking, even with the new system.

Broomfield residents pack the overflow space during a 2017 public hearing asking for a temporary moratorium on fracking. Courtesy of Laurie Anderson

Broomfield residents interviewed by Grist were not reassured by Extraction’s new technology. Kelly said the company told Broomfield that it was using the latest technology in every step of the process so far, but that the city has nevertheless had to step in multiple times after residents complained of noise and health symptoms.

“They’ve done nothing to make me feel like I can trust them and trust what they say,” said Elizabeth Lario, who lives with her husband and daughter in the Wildgrass neighborhood a little less than a mile south of the Livingston site. Lario said she and her family have experienced migraines, nose bleeds, stress and anxiety, and throat irritation since drilling began last summer.

Broomfield fought the company’s restraining order, and on April 6, the same judge who originally issued the temporary order agreed to dissolve it. He found that it was granted too soon, considering the city had not even officially taken action to delay or halt Extraction’s operations yet. But the judge also issued a warning: If Broomfield exercised its regulatory powers in a way that was “arbitrary and capricious and not rationally related to combating the spread of COVID-19,” it would be back where it started, facing more legal action from Extraction.

The judge’s warning created a new problem for Broomfield: The city’s order was designed to protect public health, but it had nothing to do with preventing the spread of the virus.

Two days after the judge dissolved the restraining order, the city council finally put its public health order to a vote, but by that point, it had become harder to justify. Anderson and other city council members tried to rewrite the order in a way that didn’t flout the judge’s ruling. If they did, they thought Extraction was likely to take them to court again and the restraining order might be reinstated.

“I kept thinking we’ll find a way forward,” said Anderson. “But sometime between that Tuesday and Wednesday it became clear that there just wasn’t a way forward that wouldn’t result in a legal battle.”

Ultimately, Anderson and the majority of the council voted the public health order down 9 to 1.

It was a devastating blow for Kelly and some other residents. As a member of the League of Oil and Gas Impacted Coloradans, a nonprofit representing community groups and residents affected by fracking, Kelly has been at the forefront of the battle with Extraction, and in the past, the city has taken bold action to protect residents. While her home is about a mile from the Livingston site, she said she’s most worried about some of her neighbors who are as close as a quarter-mile from the site.

“People that I’ve gotten to know over the last … almost seven years, who I really care about, are very close to it,” she said. “And it scares me to death.”

Broomfield residents have complained about noise, odors, and health symptoms they say are linked to Extraction’s fracking site. The company says it’s keeping emissions low. Courtesy of Laurie Anderson

‘Why didn’t you protect us?’

Leading up to that final vote, the city council was flooded with emails begging them to forge ahead with the public health order. After it decided to drop the issue, community members were on edge. Kelly said she understands why the city did what it did. But others are incredibly frustrated with the outcome. “I get so many calls from people that say, ‘why didn’t you protect us?’” she said. “They’re so concerned about their health that they would have rather seen us in court.”

One concern is what residents will do in case there is an emergency, like a major emissions release or an explosion like the one in Weld County. The Broomfield police department has told families that live within a half-mile of the site to keep a bag packed in case an evacuation is necessary. But Elizabeth Lario is not sure where her family would go. Under normal circumstances, the city’s emergency shelter is its recreation center, but as long as social distancing is necessary, that no longer feels like a safe option. “The evacuation plan is to wait and hear what the evacuation plan is,” Lario said.

An excerpt from an email sent to the city by a resident concerned about the Livingston fracking site.

On April 13, the Broomfield Office of Emergency Management held a telephone town hall to present evacuation instructions. Residents told Grist that instructions on where they should go were not very clear, and that the evacuation plan was fluid depending on the scale of emergency and the status of the pandemic. “It was a plan left in chaos, in my opinion, that fortunately hasn’t had to be used,” said Anderson.

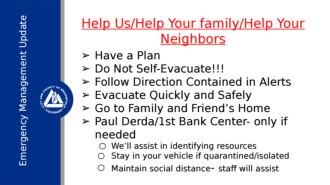

City and County of Broomfield, Colorado

The Broomfield police department told Grist that it uses a cell phone alert system for emergency notification. An “Emergency Management Update” powerpoint created by the department instructs residents to “follow the instructions you receive” and monitor the situation on the city’s social media accounts. In the case of an evacuation, it says to go to the home of a family member or friend — and to go to the recreation center only if needed. The department advises that residents who do elect to evacuate to the recreation center remain in their cars “if quarantined/isolated.”

Not all of Broomfield’s citizens are worried about the fracking site. In fact, some actively opposed the city’s idea to delay Extraction’s work. Anderson said there had been pressure from residents who felt that the city was already wasting too many public dollars on its clashes with the company, and worried that another lawsuit could bankrupt the city. A former council member accused the city of conducting a witch hunt.

Broomfield has indeed spent a significant amount of money on oil and gas oversight, including hiring additional personnel, outside counsel, and consultants. It has also deployed systems to monitor air quality and noise. The Broomfield Enterprise, a local newspaper, reported that the city spent $1.8 million in 2018, $1.5 million in 2019, and is expected to spend $3.1 million this year just on oil and gas-related personnel and programs. The city has approved approximately $1.5 million for air quality monitoring contracts in 2020 alone.

Broomfield’s air monitoring system is impressive, given that it’s a city of only about 70,000 people. The city currently has 11 new sensors set up to monitor emissions, as well as two mobile air quality laboratories and a mobile “plume tracker” — a Chevy Tahoe equipped to measure real-time methane concentrations in the air — from Colorado State University that will be deployed periodically. The city’s sensors do not measure the specific amount of benzene and other harmful compounds in the air, but they set off “triggers” to take an air sample any time they register a spike in emissions.

Anderson hopes that collecting this data will give the town a clearer picture of the public health risks fracking poses to residential communities. She said that part of the reason the town’s order was abandoned was due to a lack of data showing that flowback would put residents at greater risk. Now they are collecting that data — but by the time any potential harms come into focus, it will be too late. Residents will have been exposed.

“This community feels like guinea pigs, and I’m right there with them,” she said. “We’re doing things that we don’t have the data to show that it’s safe.”