This story was published in partnership with the Daily Yonder, with support from the IRE Freelance Investigative Fellowship Award.

In 2009, App Thacker was hired to run a dredge along the Emory River in eastern Tennessee. Picture an industrialized fleet modeled after Huck Finn’s raft: Nicknamed Adelyn, Kylee, and Shirley, the blue, flat-bottomed boats used mechanical arms called cutterheads to dig up riverbeds and siphon the excavated sediment into shoreline canals. The largest dredge, a two-story behemoth called the Sandpiper, had pipes wide enough to swallow a push lawnmower. Smaller dredges like Thacker’s scuttled behind it, scooping up excess muck like fish skimming a whale’s corpse. They all had the same directive: Remove the thick grey sludge that clogged the Emory.

The sludge was coal ash, the waste leftover when coal is burned to generate electricity. Twelve years ago this month, more than a billion gallons of wet ash burst from a holding pond monitored by the region’s major utility, the Tennessee Valley Authority, or TVA. Thacker, a heavy machinery operator with Knoxville’s 917 union, became one of hundreds of people that TVA contractors hired to clean up the spill. For about four years, Thacker spent every afternoon driving 35 miles from his home to arrive in time for his 5 p.m. shift, just as the makeshift overhead lights illuminating the canals of ash flicked on.

Dredging at night was hard work. The pump inside the dredge clogged repeatedly, so Thacker took off his shirt and entered water up to his armpits to remove rocks, tree limbs, tires, and other debris, sometimes in below-freezing temperatures. Soon, ringworm-like sores crested along his arms, interwoven with his fading red and blue tattoos. Thacker’s supervisors gave him a cream for the skin lesions, and he began wearing long black cow-birthing gloves while he unclogged pumps. While Thacker knew that the water was contaminated — that was the point of the dredging — he felt relatively safe. After all, TVA was one of the oldest and most respected employers in the state, with a sterling reputation for worker safety.

Then, one night, the dredging stopped.

Sometime between December 2009 and January 2010, roughly halfway through the final, 500-foot-wide section of the Emory designated for cleanup, operators turned off the pumps that sucked the ash from the river. For a multi-billion dollar remediation project, this order was unprecedented. The dredges had been operating 24/7 in an effort to clean up the disaster area as quickly as possible, removing roughly 3,000 cubic yards of material — almost enough to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool — each day. But official reports from TVA show that the dredging of the Emory encountered unusually high levels of contamination: Sediment samples showed that mercury levels were three times higher in the river than they were in coal ash from the holding pond that caused the disaster.

Then there was the nuclear waste. According to a 2011 TVA report, the river-bound coal ash and sediments contained higher radiation levels than the holding pond. Half of the river sediment samples taken contained cesium-137, a highly soluble compound with a 30-year half-life that can contaminate large bodies of water for well over a generation. It’s best known as the predominant source of radiation in the fallout of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster. It can cause burns, acute radiation sickness, and death. Exposure also increases the risk for cancer.

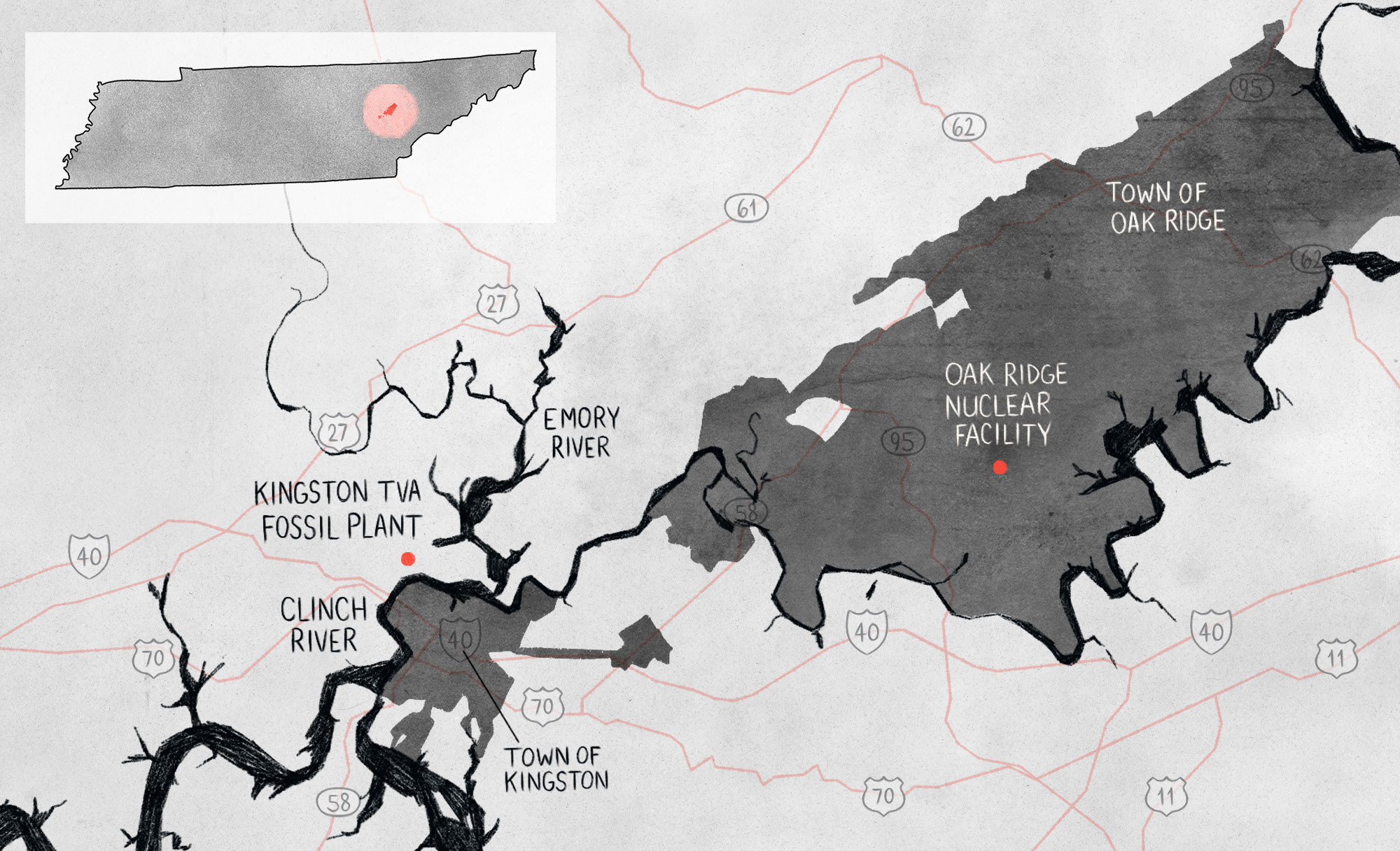

Cesium-137 also happens to be a byproduct of the nuclear reactions and weapons testing that began in the 1940s at the 35,000-acre Oak Ridge Reservation, which is roughly 30 miles upstream from Kingston. The federal facility is infamous for its role in the Manhattan Project, which resulted in the U.S. dropping twin atom bombs on Japan at the end of World War II, demonstrating the horrific effects of radiation exposure to the world.

The Kingston coal ash spill was the nation’s largest industrial disaster to date, releasing five times as much toxic material as the 2010 explosion of BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig. Workers like Thacker now wonder what they were really exposed to during the cleanup. Coal ash is toxic in its own right, but additional radioactivity may have made the dredged material more dangerous than the ash alone.

An email exchange between TVA and Thacker, who inquired repeatedly about the cause of work stoppage, indicates that the discovery of this additional contamination was responsible for the order demanding that all the dredges abandon the coal ash in the area, leaving roughly 170,000 cubic yards of contaminated material behind. Eventually, with the blessing of state and federal regulators, TVA opted for a “monitored natural recovery” of the Emory River. The utility left the ash to mix naturally with the sediment and preexisting contaminants in the riverbed, promising to monitor the process for up to 30 years to ensure that concentrations of ash-related contaminants decline over time.

While no one was killed by the 2008 coal ash spill itself, dozens of workers have died from illnesses that emerged during or after the cleanup. Hundreds of other workers are sick from respiratory, cardiac, neurological, and blood disorders, as well as cancers; the jury in a 2018 court case determined that many of these ailments could have been caused by long-term coal ash exposure. Whether or not the coal ash alone was responsible for the deluge of illnesses — and whether or not TVA was aware of exposure to additional hazards that it did not disclose to workers — remains an open question.

In response to inquiries from Grist and the Daily Yonder, a TVA spokesperson wrote that the utility’s “recovery plan was informed by the best available science on how to perform the work safely.” He did not respond to specific questions, alluding to the fact that much of the cleanup was contracted out to a firm called Jacobs Engineering. In an email to Grist and the Daily Yonder, a Jacobs spokesperson confirmed that cesium-137 was present in the lower Emory River and precluded further ash removal. She added that state and federal regulators “approved all cleanup actions” and that “comprehensive testing of water, soil, and air” directly after the spill informed a safety plan the firm distributed to workers.

The apparent mixing of fossil fuel and nuclear waste streams underscores the long relationship between the Kingston and Oak Ridge facilities. When TVA was created by the federal government in 1933 — to control regional floodwaters and provide electricity to seven states including Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi — the utility immediately got to work industrializing a region that was still, by many standards, premodern. Massive dams sprang up seemingly overnight. The natural pathways of rivers were diverted, and abandoned towns were buried beneath new lakes that fanned out like blood vessels. Hydroelectricity illuminated the surviving towns for the first time in their history. Soon after, the first of 12 coal-fired power plants rose along the newborn shorelines.

One of these was the Kingston Fossil Plant, which was constructed in 1955 to supply energy for the Oak Ridge nuclear facility. While a row of stacks spewed sulfur and carbon dioxide into the air, 10 percent of the burned coal collected at the bottom of the stacks as ash. To keep this extremely fine and feather-light material from becoming airborne dust, TVA mixed it with water and stored the resulting sludge in makeshift ponds.

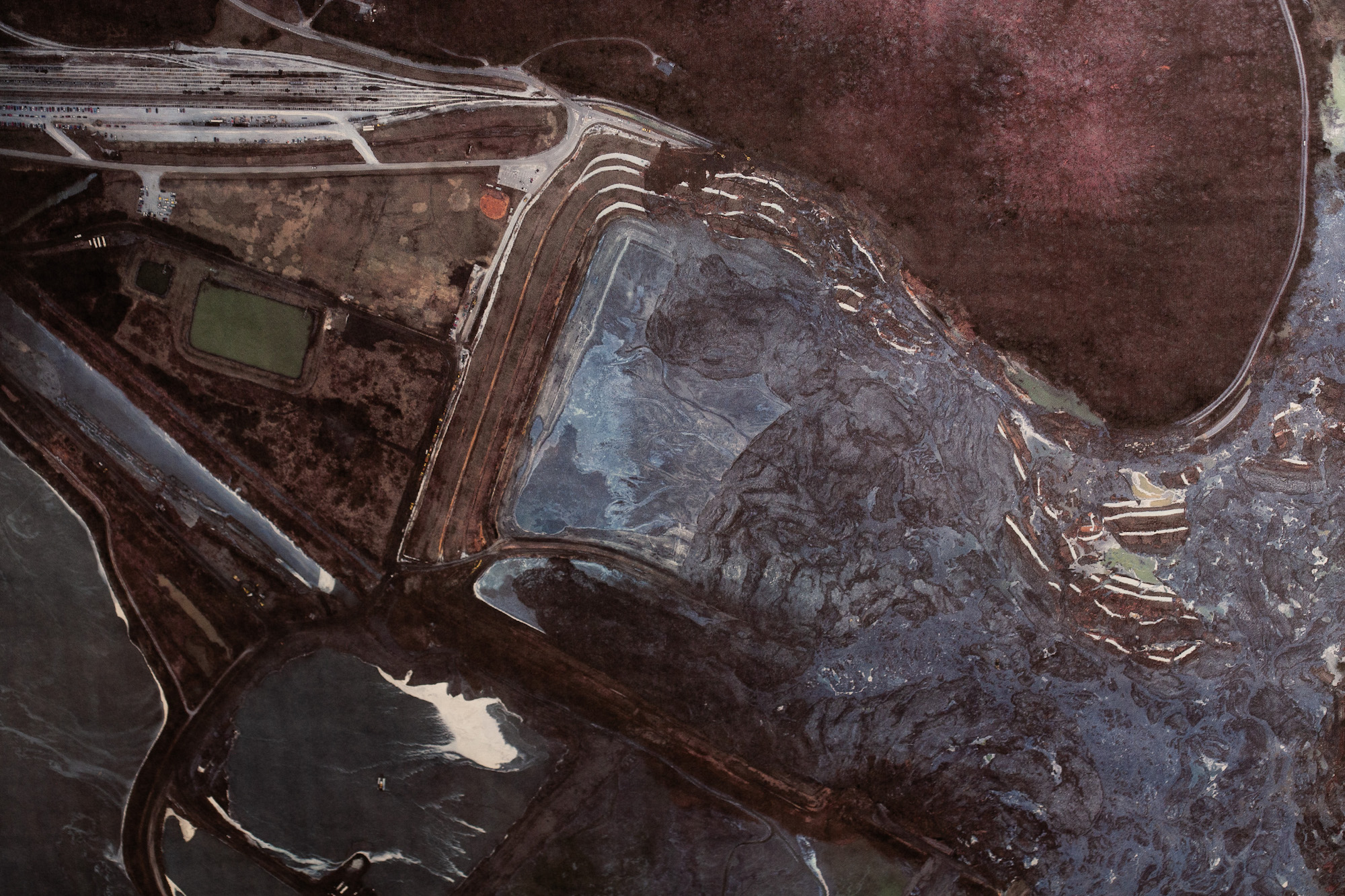

Three days before Christmas in 2008, one of those ponds burst under the pressure of over half a century of accumulated dumping. More than 5 million cubic yards of ash — a mass roughly equivalent to the amount of concrete in the Hoover Dam — overflowed into the adjacent waterway. Thick charcoal spears of it stabbed through the surface like Antarctic ice floes, except they smelled like Clorox. The coal ash pond that burst bordered a kidney-shaped section of the Emory River heavily used for recreation. TVA immediately prioritized unclogging the river, and the fleet of flat-bottomed boats Thacker worked on started dredging downstream. Time was of the essence: The spill had contaminated a river system that hundreds of thousands of Tennesseans rely on for drinking water.

Just a few miles downriver from this site, the Emory meets up with the Clinch River in a wide oxbow. Because of the spill’s proximity to the Clinch River and Oak Ridge, TVA knew the disaster could have stirred up not only coal ash — which federal guidelines do not classify as “hazardous” waste, despite its dangers — but also material that the government considers unambiguously hazardous as well. Between the 1950s and 1980s, so much cesium-137 and mercury was released into the Clinch from Oak Ridge that the Department of Energy, or DOE, said that the river and its feeder stream “served as pipelines for contaminants.” Yet TVA and its contractors, with the blessing of both state and federal regulators, classified all 4 million tons of material they recovered from the Emory as “non-hazardous.” It took six years to clean up the entire site, during which workers toiled in the ash unprotected, without the gear routinely required at hazardous waste sites.

TVA documents obtained by Grist and the Daily Yonder, including confidential presentations and internal comments on Kingston cleanup plans, as well as emails and reports unearthed during court proceedings, show that TVA knew that hazardous material from Oak Ridge could interfere mightily with their cleanup efforts. Although one report states that cesium-137 wasn’t found in material dredged from the river, the compound did appear in over half of sediment samples taken from the river itself. How TVA could have prevented this especially radioactive material from mixing in with the material dredged out of the river — and therefore from being handled by more workers on shore, and ultimately shipped to a landfill in Alabama — is unknown. Regardless, workers weren’t informed that encountering such material was even a possibility.

Interviews with those involved in the cleanup and sworn declarations in court indicate that workers were in contact with unambiguously hazardous material, including discarded barrels with nuclear hazard symbols. A documented spike in radiation readings at the site, which state regulators deleted without explanation from public reports in 2009, has raised further questions about the extent of worker exposure.

TVA did not acknowledge these dangerous risk factors publicly. Doing so could have triggered a far more expensive and more stringently regulated cleanup, as well as a stain on the utility’s upstanding reputation. Instead, TVA and its contractors failed to inform workers about the known possibility that unusually high levels of radioactive contamination could put their lives in danger. Whether this potential coverup caused or exacerbated any of the cluster of illnesses that has killed at least 51 former workers since the spill — and wreaked havoc on the lives of hundreds more — may never be known.

I met App Thacker at the Hones Point Campground in Pendleton, Kentucky, under the clear sky of early evening last spring. Clad in a faded black T-shirt, jeans, and big brown work boots, he sat at a picnic table with Angie, his wife of 24 years. He told me that he believes he was exposed to radioactive material eight to 10 times per shift for approximately 18 months, and he submitted two official complaints to this effect. He said he asked his supervisors roughly a dozen times about the nature of the work stoppage in 2009-2010. According to Thacker, his bosses admitted that it was due to the discovery of radiation, but they insisted he had “no more exposure than an X-ray.” Thacker alleges that no additional information was provided, and no exposure tests were conducted on any of the workers.

Thacker isn’t the only worker who remembers the night the dredges stopped. Kenneth Shepherd, who operated a dredge alongside him, remembers an urgent call over the radio telling him to get out of the river. Two other operators on land, Terry Ellers and Craig Wilkinson, also remember the call. Ellers told me that much of the mysterious radioactive “hot stuff” discovered in the river that night was almost surely removed and shipped out of state along with the ash. He said that his own supervisors didn’t take any precautions to keep workers from being exposed to radiation. Shaken, Ellers asked to be laid off a few weeks later, calling it “one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.”

In June 2013, almost three years after Thacker’s first complaint about radiation exposure, he got a call from Philip Davis, a representative of TVA’s Employee Concerns department. Davis told Thacker that TVA found the claims he’d made to be “unsubstantiated.”

Thacker wasn’t satisfied. Two months after the phone call, he joined a 49-person civil suit against Jacobs. The suit, which has since ballooned to over 200 plaintiffs, alleges that Jacobs neglected worker health and safety by denying them protective equipment like respirators, Tyvek suits, and even basic dust masks. In November 2018, a jury in Knoxville agreed that a litany of illnesses workers have developed — from lung cancer and leukemia to rare blood disorders and severe respiratory conditions — could have been caused by their exposure to coal ash.

When Davis dismissed Thacker’s complaint back in 2013, he based his decision on reading a 2-year-old report on the Kingston dredging operation. Co-written by TVA and Jacobs, the report corroborates Thacker’s memory: Dredges stopped running through the final section of the Emory and turned around because this section contained so-called “legacy contamination” — TVA’s nickname for nuclear waste abandoned by DOE facilities like Oak Ridge.

In internal TVA emails, Davis said he informed Thacker that cesium-137 stopped the dredging, but he didn’t include details of its deadly effects or even a description of the substance. If containers of cesium-137 are opened, the radionuclide looks like a white powder. Jeff Brewer, a truck driver, described such a powder in an interview with me this spring. Brewer told me he was hauling ash and dirt from a newly dug ditch at the Kingston spill site when an operator in a trackhoe ripped a barrel of white powder out of the ground. The black lid of a 55-gallon drum dangled off the end of his bucket, while two or three more drums sat uncovered in the ditch below.

“Of course that powder flew everywhere, so [TVA and Jacobs supervisors] came out and tried to tell us it was dried-out diesel fuel,” Brewer told me. “My great uncle drove trucks, and I’ve been on a farm all my life. Diesel fuel doesn’t dry up like chalk powder. I don’t know what was in them barrels, but we were told to move from that area.”

One worker who ran dredges told Brewer that he’d hit unexpected radioactive material in the river, but Brewer says company officials and supervisors never announced this finding. “They never told us anything about hitting that radioactive material,” he said. “It came through the workers who was talking to each other. Neither TVA or Jacobs acknowledged that it happened.”

Sworn declarations from two different workers who dredged the river between January and August 2009 say that they “personally observed barrels being removed from the river” and “personally observed approximately two hundred fifty (250) blue metal barrels stored near the wash bay.” Both workers claimed that they saw more than a dozen barrels marked with nuclear hazard symbols lined up on the river’s bank. According to the workers, the remnants of at least one rusty blue barrel with a failed seal were lifted out of the waterway with a dredge head. They were informed that the dredge was tested with a Geiger counter, and then the entire machine was taken out of service and anchored far from shore. The workers also claimed that they asked for dust masks, Tyvek suits, and clean water but were never given any. They had to wash their hands and boots with contaminated river water. (The declarations were part of a lawsuit that county officials filed against Jacobs and TVA last year; Jacobs argues that the suit’s claims “lacked merit,” but ultimately the case was dismissed on procedural grounds.)

Thacker believes no dredges ever returned to the river section where the work stoppage occurred. He says the dredges also weren’t cleaned after hitting this material. The coal ash left behind was never removed from the river, either. Instead, operators like Thacker re-dredged different sections of the Emory for another year until enough material was removed for Jacobs to receive almost a million dollars in bonuses from TVA.

A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency analysis confirms that the ash that was left in the river was “found to be commingled with contamination from the Department of Energy (DOE) Oak Ridge Reservation site. Oak Ridge Associated Universities conducted independent medical screening and concluded there were no adverse health impacts caused by the coal ash spill.” According to a TVA memo, roughly 510,000 cubic yards of ash were left behind across 200 acres of Tennessee waterways, an area roughly two-thirds the size of Chicago’s Grant Park.

“I can take you, a jury, or anybody else on a pontoon boat with a 20-foot stick of PVC pipe and shove in anywhere down there and pull you out a sample,” Thacker told me flatly. “It’s still there.”

For nearly a century, both Oak Ridge and TVA treated their waste with less care than most families treat household garbage. It was often dumped into unlined, and sometimes unmarked, pits that continue to leak into waterways. For decades, Oak Ridge served as the Southeast’s burial ground for nuclear waste. It was stored within watersheds and floodplains that fed the Clinch River. But exactly where and how this waste was buried has been notoriously hard to track.

In 1958, a fire destroyed waste records from Oak Ridge’s first decade of existence. Then, in 1982, a local paper uncovered 2 million tons of mercury leaking into the Clinch from Oak Ridge’s Y-12 facility, a national security complex where uranium was enriched to build the first atomic bombs. The short-lived federal investigation that followed found that Oak Ridge still had no storage records for roughly 12 million cubic feet of radioactive waste, enough to fill the University of Tennessee’s football stadium, which holds more than 100,000 people. At the behest of state regulators and the federal government, TVA assumed the role of Oak Ridge’s environmental watchdog, despite having almost no legal enforcement authority.

David Freeman, the utility’s CEO at the time, sent TVA officials to inspect Y-12 after the mercury leak was discovered. He reported that they found additional “highly toxic items,” including radioactive elements like uranium, thorium, and plutonium, discharged into surrounding waterways. During the federal investigation, Dean Hill Rivkin, a board member with the Legal Environmental Assistance Fund, testified that nearby residents were concerned that disturbances to the Clinch riverbed would unearth sediments containing mercury and radioactive waste.

In 1991, TVA joined the DOE, EPA, and state regulators in an agreement intended to mitigate activities that could disturb legacy contamination in the Watts Bar Reservoir, 30 miles downstream from Kingston. Less than two decades later, even though top management had known about the deeply contaminated waterways for years, TVA began dredging a section of the Emory that sits at the geographic midpoint between Oak Ridge and Watts Bar.

Documents obtained by Grist and the Daily Yonder prove that TVA knew that dredging could unearth hazardous material. Dee Stewart, a deputy director at the EPA, submitted official comments on TVA’s initial dredging plan in February 2009, noting that material dredged from the river would need to be tested for hazardous constituents. If hazardous elements that weren’t typically found in coal ash were discovered above safe limits, the whole soup of ash and sediment “would have to be considered newly-generated hazardous waste and managed as such,” Stewart wrote.

In the same document, Steven Alexander, head of contaminants at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, also urged TVA to “consider radionuclide analyses of the dredged material as well as existing sediments that may be removed during the dredging process.” TVA told Alexander that their first of three phases of dredging wouldn’t disturb legacy contaminants. But they acknowledged that the second phase, which involved digging deeper into the riverbed closer to the Clinch, might. TVA said they’d focus on “minimizing disturbance of legacy sediment.”

Dredging this sediment, mixing it in with the recovered coal ash, and categorizing the concoction of Kingston’s coal ash and old nuclear waste as “newly-generated hazardous waste” could have been catastrophic for TVA — the nuclear sediments would have touched almost every part of the cleanup operation.

Consider the legacy waste in the riverbed as a handful of sand. After it leaves the river, the ultra-fine material encounters Kingston’s long assembly line: First, it’s dredged by operators like Thacker. Then long pipes shoot it from the river into a series of canals and holding ponds, further mixing it in with the coal ash. Massive machines like dump trucks and trackhoes disperse it onto a plateau that TVA called the Ball Field. There, the tiny particles dry in pancake-like piles across the plain. On particularly windy days, they spin into dust devils with the ash, covering the sky like curtains 100 feet in the air. Once it’s dry enough, the combined coal ash and nuclear material is scooped onto a rail line for shipment to a solid waste landfill 350 miles south in Uniontown, Alabama.

Between the Emory and this landfill, hundreds of workers handled the ash. Fugitive dust escaped to nearby communities across two states. Nearly 40,000 train cars eventually dumped the ash in Uniontown, a low-income, 90-percent-Black community near Selma. Prior to the first shipment in June 2009, the ash was tested for radionuclides to make sure it fell below Alabama’s threshold for radium. Samples showed radium levels up to two times the Alabama Department of Public Health’s limit. But the company that owned the landfill argued it should be exempt from the limit, because its own evaluation determined that workers were safe at exposure levels over eight times Alabama’s limits. The state’s public health department granted its request, doubling the threshold for radium exposure.

That same summer, all workers hired at Kingston were required to take a 40-hour training in Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response, or HAZWOPER, approved by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA. Though coal ash is not a federally regulated hazardous waste, the training was required because materials within the ash (like arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, selenium, and zinc) are individually regulated as hazardous. Most workers took the training in a nearby laundromat or at a local school. Brad Green, a foreman at the Kingston site, testified in the 2018 trial that it was hard to stay awake during the training because workers thought the information about hazardous waste did not pertain to them. “It wasn’t nothing about coal fly ash,” he said. None of the workers who spoke to me heard anything from their supervisors, or those conducting the training, about possible exposure to hazardous waste at Kingston, and they were not given the baseline or follow-up physicals that are legally required at official hazardous waste sites.

Within four years, workers were sharing stories of plummeting testosterone levels, a symptom that multiple studies have linked to radiation exposure like that experienced by male cancer survivors who have undergone chemotherapy. Men in their 30s and early 40s started taking testosterone injections. Brewer, the truck driver, had his levels plummet by 75 percent. Now, at 46 years old, he takes a shot for his testosterone every other week. Thacker, the dredge operator, was told by his doctor that he had the testosterone levels of a man twice his age. When he reported this symptom to Jacobs, however, Thacker says he was laughed out of their offices.

Dismissal of worker health concerns by TVA is well-documented in recent years. In June 2013, another truck driver named Joe Pursiful submitted an official complaint claiming that a supervisor mocked men on site complaining about low testosterone. “It’s a joke,” the supervisor told Pursiful. “I’ll take up their slack.” (Pursiful died earlier this month, at the age of 61.) In an anonymous complaint to TVA’s Office of Inspector General the following month, another worker claimed that he and others were experiencing bronchial infections, sinus infections, and low testosterone. Nobody took their symptoms seriously. A different supervisor said “the workers were making up the health issues to avoid being laid off,” according to the text of the complaint.

Meanwhile, OSHA did little to ensure its training was implemented. Two months after the spill, OSHA received an anonymous complaint that employees were working in hazardous conditions due to TVA’s negligence. But the agency chose not to act. “OSHA has decided not to conduct an inspection in response to this report,” an agency official wrote to TVA. “However, since the allegations of the violation of standards have been made, you should investigate the alleged violations.” Even as TVA was responsible for investigating itself, the utility was paying Jacobs $12,500 for every month that zero OSHA violations were identified at the site. (According to the Jacobs spokesperson, there were no OSHA violations during the time the contractor was on site.)

A spokesperson for the Department of Labor, the cabinet agency that oversees OSHA, did not respond to Grist and the Daily Yonder’s inquiry about the complaint in question but suggested that standard procedures were followed. “OSHA investigates all safety and health violation allegations within the agency’s jurisdiction,” the spokesperson wrote.

TVA was forced to institute HAZWOPER training in the summer of 2009 because of a new EPA order that governed the site. The order, which stemmed from the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, Respondent, and Liability Act, or CERCLA, entered Kingston into the nation’s Superfund program. Enrolling in Superfund, which typically monitors hazardous waste sites like old chemical plants and defunct nuclear stations, turned out to be both a blessing and a curse for TVA. On the plus side, CERCLA granted TVA access to a pot of federal cleanup money. On the other, it made the consequences of discovering hazardous material above certain thresholds even more severe.

If hazardous materials were found co-mingling with the coal ash, Superfund law could trigger a change in how the site was managed, officially recategorizing Kingston as a hazardous waste site. The entire cleanup operation would fall under more stringent, more expensive, and more time-consuming guidelines. Cleanup workers, for example, would be required to wear respirators and limit their exposure time. TVA could be vulnerable to new legal claims in both Tennessee and Alabama for initially treating the waste as though it were non-hazardous. (An EPA spokesperson declined to answer specific questions, but he confirmed that the agency approved all cleanup procedures and claimed that TVA was the “lead federal agency” implementing the order.)

Understanding the EPA order requires jumping down a legal rabbit hole. In 1976, Congress passed the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, or RCRA, which separated household and industrial waste into two separate categories: hazardous and non-hazardous. The mining industry, fearful that increased regulation of its waste materials would run up costs, lobbied Congress for a loophole. Four years later, lawmakers approved an amendment that essentially excluded mining waste from being deemed hazardous, even though much mining activity involves materials considered hazardous under RCRA law. Coal ash, in particular, contains dozens of constituents the EPA considers hazardous.

While the EPA does not list coal ash or coal-fired power plants as a typical source of radiation or radioactive waste, the ash can contain elements emitting radioactivity at 10 times their naturally occurring levels. These higher levels are due to unstable atoms undergoing radioactive decay; their frequencies can be dangerous for people who touch, ingest, or are simply near them. But lobbying from the coal industry has kept more than 3 billion tons of coal ash over 1,400 U.S. sites largely exempt from federal regulation. (In 2015, the Obama administration tried to force the closure of unlined coal ash ponds with new regulation, but the Trump administration weakened the rule this year, installing a loophole that could extend the lives of the ponds.)

“All energy utilities are having a problem admitting that they’ve been using material for the last 50 years that should be kept away from the environment, and weak regulations allow them to do that,” said Avner Vengosh, a professor of geochemistry and water quality at Duke University. “For them, saying it’s hazardous material is the last thing they would do.”

Discovering legacy contamination — hazardous waste not subject to the loophole for coal ash — might have required TVA to do just that. The EPA’s Dee Stewart had warned TVA about the “potential implications” of nuclear legacy waste mixing in with their “non-hazardous” waste. According to TVA’s responses to Stewart’s comments, the utility teamed up with the DOE to analyze sediment samples from the Emory and Clinch Rivers for legacy contaminants. A TVA report published in early 2011 states that ash sampling showed cesium-137 within the Emory, but not in the ash taken out of the river. This discovery led to the work stoppage on the final section of the Emory, but it’s unclear if it had any other effect on the way the broader cleanup operation was conducted.

Additional internal documents obtained by Grist and the Daily Yonder demonstrate that TVA was aware that worker exposure to cesium-137, or other forms of legacy contamination, could be a financial and legal nightmare. In July 2009, two months after the CERCLA order, TVA officials gave a confidential internal presentation in which they said that one of the most severe risks to their bottom line would be stopping or altering the cleanup plan they’d already put into place.

In an affidavit from the 2018 trial, a foreman indicated that this fear had been internalized by workers on the ground. According to the affidavit, a Jacobs safety manager, with the support of TVA supervisors, ordered his workers to remove personal protective equipment and destroy common dust masks. (At the onset of the cleanup, many workers had supplied their own safety gear or acquired it from Kingston’s utility room.) The supervisor allegedly stated “that the site was a CERCLA site and that if they wore dust masks or respiratory protection, it would change the status of the site.” A heavy equipment operator recalled at trial that this same safety manager once told him: “If these people knowed what was in this ash, they’d quit.”

In response to allegations that appropriate personal protective equipment was not provided and even discouraged due to the site’s regulatory status, the Jacobs spokesperson told Grist that “the site’s designation as a CERCLA site was not and could not have been based on the use of respiratory protection.” She added that, although plaintiffs alleged they were denied dust masks during the 2018 trial, “we are not aware of any instance in which respiratory protection was denied to a worker who requested it and met the applicable criteria” under the site’s official safety plan.

According to court records, however, early versions of this plan did not list all the constituents in coal ash, including radioactive material. Only four employees ever managed to obtain Jacobs’ approval to secure and use dust masks, though records indicate that dozens asked. Court records also confirm that dust masks were destroyed on site by Jacobs supervisors. No one at the spill site ever received a respirator.

During TVA’s 2009 presentation in the wake of the CERCLA order, the utility worried that the number of health problems could rise if levels of radiation and heavy metals in the coal ash “are deemed to be higher than first reported.” Such radiation levels could lead to another risk: class action lawsuits.

According to recently reported documentation that dates back to the year after the spill, radiation levels were, in fact, much higher than first reported.

In 2017, a former chemist named Dan Nichols stumbled upon a news story that revealed the existence of the additional health problems TVA feared. High levels of uranium had been measured in the urine of a former cleanup worker named Craig Wilkinson. Like Thacker, Wilkinson had worked the night shift. After dredges piped the coal ash back onshore, Wilkinson used heavy equipment to scoop, flip, and dry the wet ash along the Ball Field.

Although Wilkinson worked at the Kingston site for less than a year, he quickly developed health issues, including chronic sinus infections and breathing problems that eventually led to a double-lung transplant. Frustrated by his sudden decline in health, Wilkinson shelled out over $1,000 for a toxicology test because he wanted to know what occupational hazards might be lingering in his body.

After reading Wilkinson’s story, Nichols sat stunned. Though he was not associated with the spill, he’d been unable to shake his obsession with the Kingston disaster. Nichols had worked as a Memphis-based field chemist for a wastewater technology company, and he was used to studying lab reports on industrial water supplies and samples. For years he’d been trying to solve a mystery that no one else seemed to be aware of: why Kingston regulators deleted and then altered a state-sanctioned report showing extremely high levels of radiation at the cleanup site.

Roughly a month after the spill, Nichols read a Duke University press release stating that ash samples collected at Kingston by a team led by Vengosh, the geochemist, showed radium levels well above those typically found in coal ash. Nichols knew that the state environmental regulator, the Tennessee Department for Environment and Conservation, or TDEC, was also testing soil and ash samples at the site. After seeing Vengosh’s high radium readings, he wondered if TDEC’s report would also show high levels of either radium or uranium. (Radium is a decay element of uranium.) Later that spring, Nichols visited TDEC’s website and discovered the test results.

“I opened it up and went to uranium, and it was just off the charts,” Nichols recalled. In a 2020 affidavit, Nichols reported that these levels were “extremely high so as to be alarming.” At least 27 soil and ash samples were collected from at least 20 different sites surrounding Kingston beginning January 6, 2009. The levels ranged from 84 parts per million (ppm) to 2,000 ppm. The average level was over 500 ppm, as much as 50 times the typical uranium content found in coal ash.

The next morning, when Nichols slumped back into his computer chair and refreshed TDEC’s website, he saw that the report had been changed. The high uranium readings had plummeted. Now the average uranium levels in the ash were 2.88 ppm, a tenth of the typical uranium content found in coal ash and illogically, below levels naturally occurring in soil. Luckily, Nichols had downloaded the unaltered report the night before.

A month later, Nichols sent the two lab reports to one of the attorneys representing Tennessee residents affected by the spill in a lawsuit they’d brought against TVA. According to Nichols, the lawyers weren’t interested. Nevertheless, Nichols was determined to find more proof of the unusually high levels of on-site radiation. In between cutting hay and spraying weeds on his family farm, he spent years poring over information online about TVA, coal ash, and uranium before he stumbled across Wilkinson’s story.

Back in 2014, Wilkinson’s urine tested for unusually high levels of both mercury and uranium. The mercury is more easily explained: The most common cause of mercury contamination, according to the EPA, is coal-fired power plant emissions, which account for 44 percent of all man-made mercury pollution. The 2008 spill released 29 times the mercury reported at the Kingston site for the entire decade before it, and TVA documents show high levels of additional legacy mercury were present in the Clinch River and could have migrated into the Emory. Today, Wilkinson has symptoms attributable to methylmercury poisoning including blurry vision, fatigue, a hearing impairment, memory loss, and loss of coordination that caused him to fall out of the machines he operated until retiring on disability in 2015.

But most shocking to Nichols was the high level of uranium in Wilkinson’s body — it was 10 times the U.S. average, and identical to the median levels that one study found in workers exposed to the substance. Prolonged occupational exposure to uranium is strongly linked to chronic kidney disease, which Wilkinson suffers from. Because Wilkinson’s toxicology results were taken four years after he left Kingston, they likely show lower uranium levels than what he and other cleanup workers initially had.

Wilkinson’s results left no doubt in Nichols’ mind that the original uranium readings he’d saved were significant. A reporter for the Knoxville News-Sentinel, Jamie Satterfield, contacted him after the report he saved showed up in court proceedings. Satterfield published a story about the altered uranium readings in May of this year.

In response to her story, TDEC told the News-Sentinel that its updated uranium readings, which plummeted by 98 percent, were due to a change in the sampling method used for the tests. (Satterfield also reported that radium levels had been lowered between the initial TDEC report Nichols downloaded and the updated one; the department attributed this to a “data entry error.”) In an email response to Grist and the Daily Yonder, a TDEC spokesperson elaborated that the sampling lab, which was neither staffed nor supervised by TDEC, “discovered there were interferences in the analysis of soil and ash samples for uranium” and subsequently changed the method of analysis from one EPA-approved protocol to another. The new results were then published without public notice of the alteration.

“Changing lab reports is a very serious thing,” Nichols said. “But I can assure you data entry errors don’t cause a man to test for unusually high levels of uranium. That’s [TDEC’s] big problem.”

Unbeknownst to Nichols, Russell Johnson, the district attorney with jurisdiction over Roane County, where Kingston is located, had informed TDEC’s commissioner in 2017 that he was beginning a criminal probe into the Kingston cleanup. “I am deeply concerned with the apparent intentional conduct of the cleanup contractors and their supervisors, actions that took place in Roane County, conduct that may indeed have caused serious bodily injury or possibly even death to a number of people,” Johnson wrote in a letter to TDEC.

In concert with the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, Johnson began investigating whether TVA or its contractors “suppressed information” as part of the coverup alleged in the 2013 worker lawsuit against Jacobs. They now have Nichols’ evidence as well. But despite this ongoing investigation, it’s unclear if workers will ever learn for certain whether or not they were exposed to dangerous substances besides the coal ash itself. (Bob Edwards, an assistant district attorney working under Johnson, told Grist and the Daily Yonder that the district attorney’s office could not comment on a pending investigation.)

For residents who have lived in the region for generations, however, the illicit off-site dumping of nuclear waste from Oak Ridge is an open secret. Doug Bledsoe, a former cleanup worker, told me that his father worked at Oak Ridge and dumped nuclear waste at the bottom of a coal ash pond. (Bledsoe died of brain cancer in August.) When Angie Thacker worked in a hair salon in town, she recalls old men coming in and telling her that they dumped barrels of nuclear material into the Clinch River. A lifelong resident of Oak Ridge, she remembers learning at an early age not to play in the rivers. (The DOE, which manages the Oak Ridge facilities, did not respond to Grist and the Daily Yonder’s requests for comment.)

Now Angie’s husband is another of the hundreds of examples of people with snowballing health issues tied with Kingston. After the dredging operation ended, App Thacker started operating machines around the Ball Field, but the continual dust exposure led to new skin lesions, high blood pressure, and bronchial infections he couldn’t kick. He eventually cracked his ribs from coughing, and today both Thacker and his wife have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He has since developed depression and anxiety, which he still takes medication for today.

Thacker never stopped asking questions while he worked at Kingston. Eventually, he says he was called into a meeting with a TVA supervisor. Thacker told him of the open secret that workers whispered about throughout the site: Radioactive material was dredged from the river and mixed into the coal ash they handled unprotected. (Though the supervisor could not be reached for comment, he confirmed that he’d heard about the dredging of radioactive material from other workers in a 2018 deposition.)

After hearing his story, Thacker remembers the supervisor throwing a rock and saying, “I guess what you’re trying to tell me is we loaded all that shit to Alabama.”

“Yes,” Thacker replied. He was laid off a few weeks later.

This story is a collaboration between Grist and the Daily Yonder, a nonprofit news platform that covers rural issues. Learn more at dailyyonder.com.