I was a college student living in the Eagle Rock neighborhood of Los Angeles when the 1992 riots rocked my adopted city. Then, as now, law enforcement’s behavior triggered massive protests. After Rodney King led law enforcement on a high-speed chase, a group of Los Angeles Police Department officers savagely kicked and beat King with their batons more than 50 times, fracturing his skull, breaking bones, and leaving him with permanent brain damage.

All of this was caught on video by a bystander. But despite the incontrovertible evidence, a predominantly white Simi Valley jury acquitted four LAPD officers of using excessive force against King, who was black. Soon after, Los Angeles residents took to the streets. I remember feeling the disconnect between the verdict and what my eyes clearly saw on the video, and it shook me. It unnerved my fellow students at Occidental College, and I remember feeling reassured when our then-President, John Slaughter (the first African American president in Occidental’s history) offered students a public space to speak out about the acquittal, the riots, and anything else that was on our minds. To be able to come together to voice discontent, frustration, and anger gave students an outlet. But as I’ve learned since then, speaking out is just the first step. Unmasking the rot in the system is the second.

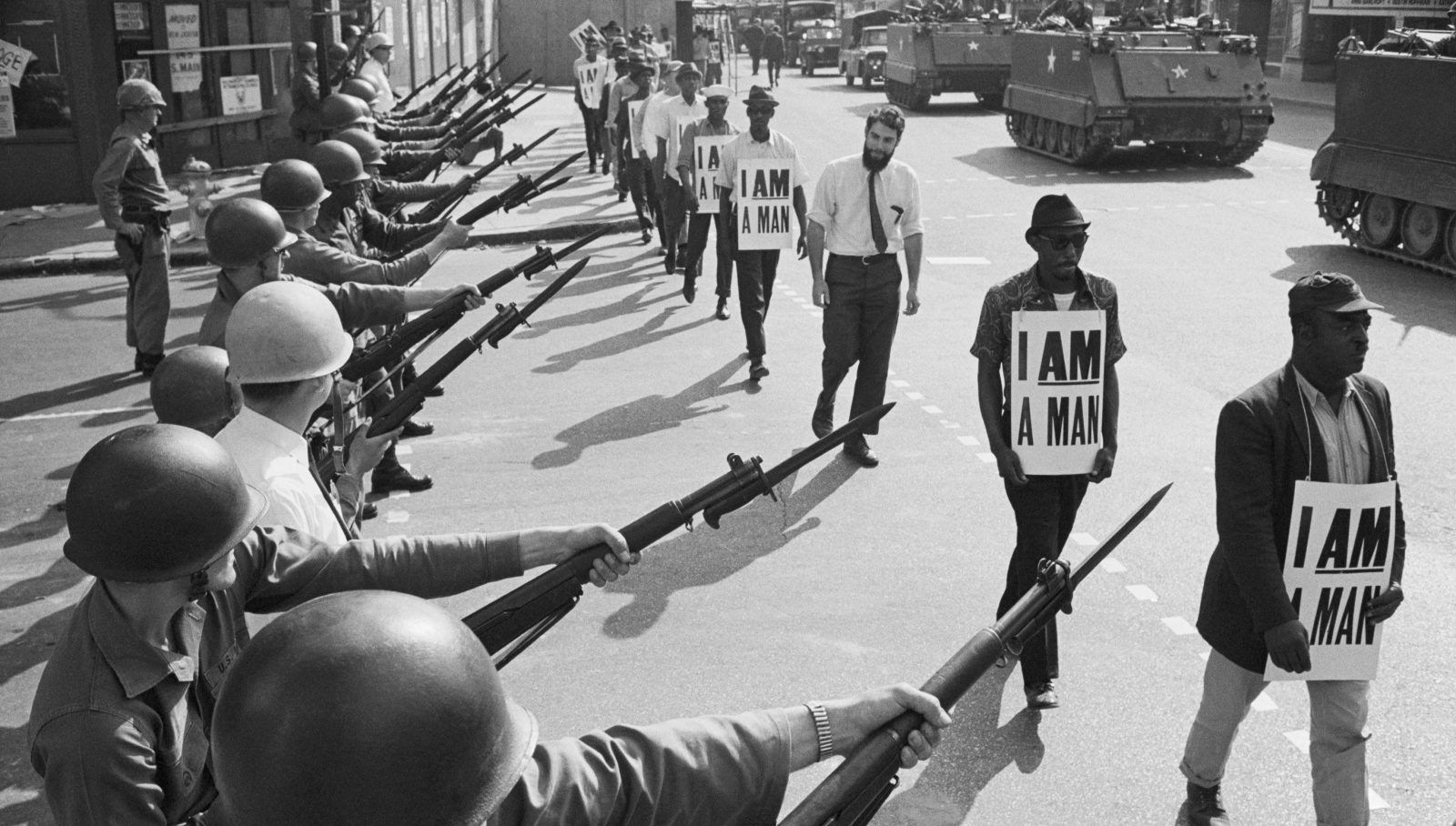

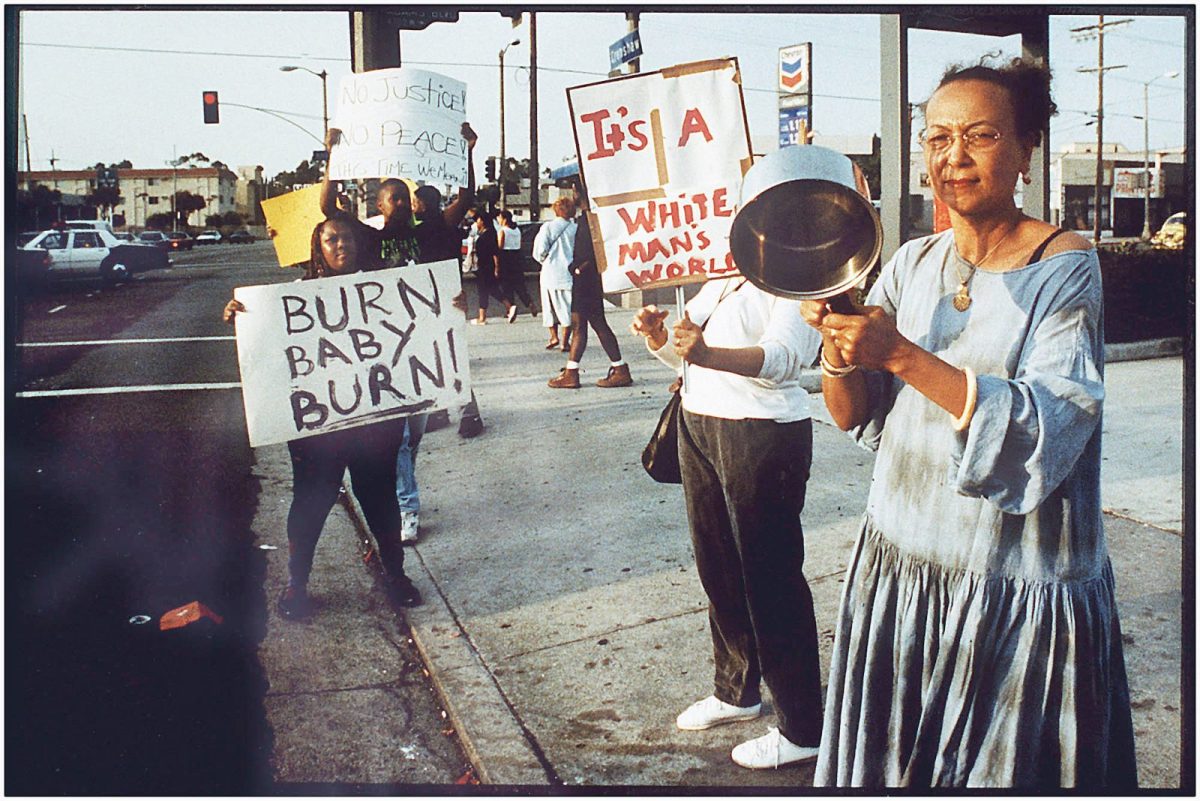

Residents of Los Angeles protest in 1992 after a group of police officers were acquitted of the beating of Rodney King. Kirk McKoy / Getty Images

Too many Americans ignored the rot that Los Angeles residents were protesting then. Now, three decades later, our nation is once again roiled by violent protests and civil unrest in the wake of George Floyd’s killing. Floyd, a 46-year-old Minneapolis resident, was pinned down by officer Derek Chauvin while being detained for allegedly using a counterfeit $20 bill at a convenience store. Videos show Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck despite Floyd’s pleas for mercy, “I can’t breathe, man,” Floyd says in one video posted by CNN. “Please, let me stand. Please, man.”

Frustrated, angry protesters took to the streets in dozens of U.S. cities this past week, a great majority marching peacefully. Others did loot, torch, and vandalize businesses and other property. Images of a gutted post office and a torched police precinct in Minneapolis have come to symbolize the unrest for many who are reading the news.

Those readers might be asking what is achieved by taking these protests to the streets. On Saturday, after another night of unrest, the Washington Post summarized its account of the protests with a headline that read: “Gripped by disease, unemployment and outrage at the police, America plunges into crisis.” That headline presumes that we weren’t already in crisis. For the working poor, for communities of color, for marginalized communities living in polluted and contaminated environments across America — for all who live under the yoke of a system that treats Americans unfairly, unequally, and unjustly — the United States has been in crisis since the founding of our country. The wreckage we are witnessing is what happens when a nation refuses to reckon with those injustices. As South Minneapolis resident Yvonne Passmore told the Post: “This isn’t just about George Floyd. This is about years and years of being treated as less than people — and not just by police. It’s everything. We don’t get proper medical [care]. We don’t get proper housing. There’s so much discrimination, and it’s not just the justice system. It’s a whole lot of things.”

Demonstrators march in Minneapolis following the death of George Floyd. Julio Cortez / AP Photo

If you’re asking why people are so angry, look no further than the vulnerable communities that for decades have borne the brunt of environmental contamination and pollution — from petrochemical facilities, waste incinerators, oil refineries, and freeways — and are now in the crosshairs of COVID-19. Inaction has led to generations of people exposed to air pollution, poisoned groundwater, and lead-contaminated soil, resulting in a lifelong trajectory of health inequities. These neighborhoods are often the poorest, places where gunshots ring through the night, where police and probation officers patrol the streets — places where even libraries and fully-stocked grocery stores are scarce. Children come home to crowded apartments, study at some of the worst-performing schools, and are labeled gang members simply because they’re growing up on the wrong side of tracks.

This inequity is something that the writer and activist James Baldwin so eloquently addressed in The Fire Next Time, which he published at a critical moment for the civil rights movement in 1963. He argued that there is no possibility of real change in the status of African Americans without the most radical and far-reaching changes in the country’s political and social structure. Baldwin originally wrote part of the book as an essay for his nephew to mark the 100th anniversary of the emancipation of enslaved Americans. Despite the Emancipation Proclamation, Baldwin argued, American society was rebuilt on a separate and unequal foundation. Progressive steps toward racial equality were often gestures of tokenism. They never fixed the flaws, the “hard problems,” within our systems, so gaping disparities in areas like education and criminal justice persisted. By refusing to examine and confront those hard problems, the American dream had become a “nightmare,” wrote Baldwin. He warned of a reckoning: “The Negroes of this country may never be able to rise to power, but they are very well placed indeed to precipitate chaos and ring down the curtain on the American dream.”

So the curtain came down.

Just two years later, the Watts Riots were triggered by the arrest of an African American driver by a white California Highway Patrol officer. Six days of protests and violence centered in this predominantly African American neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles left businesses burned and looted, more than 100,000 people injured, and 34 dead. A gubernatorial commission found that the riot stemmed from the community’s “long standing grievances and growing discontentment with high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and inadequate schools.”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. addresses a group of residents in the wake of the 1965 Watts Riots. Bettmann / Getty Images

Martin Luther King Jr. famously practiced a non-violent philosophy, but in his “The Other America” speech in 1967, he described a riot as the language of the unheard: “And what is it America has failed to hear?… It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice and humanity.”

What protesters are marching for — then and now — are legitimate, long-standing calls to reform the criminal justice system, as well as every other system that oppresses, whether it’s in the realm of education, politics, or healthcare. Some, like the philosopher Cornel West, argue that the past week’s actions are a revival of work left unfinished in the 1960s.

“In the ‘60s, you had masses out there. Now you’ve got a younger generation of all these different colors and genders and sexual orientations saying: ‘We won’t take it any longer,’” West, a professor of the practice of public philosophy at Harvard, told CNN’s Anderson Cooper on Friday. “What’s sad about it though, brother, at the deepest level, it looks as if the system cannot reform itself.”

When that happens, said West, people of color, the poor, and the working class are left out, feeling powerless, helpless, and hopeless. It’s at that point that a rebellion takes hold: “We’ve reached the point now: It’s a choice between non-violent revolution — and by revolution, what I mean is the democratic sharing of power, resources, wealth, and respect — if we don’t get that kind of sharing, you’re gonna get more violent explosions.”

A protester carries a U.S. flag upside down next to a burning building on May 28, 2020, in Minneapolis. Julio Cortez / AP Images

Words are not enough. It takes collective action to dismantle a system and put another its place. This is why James Baldwin also spoke of the “we” — the “relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks” — working together to change minds. To suppress the “we” embodied by these protesters would be to extinguish the fire of rage within us that can fuel the tougher job of fixing the system. This work includes examining how local police use unreliable databases to track and arrest young black and brown men, and how county-level prosecutors use existing gang laws to label people as gang members in order to increase their sentences. The recent uprisings, the Public Enemy frontman Chuck D wrote on Sunday, have helped young folks recognize and confront their local officials and authorities. His own favorite Public Enemy song of protest is 1992’s “Hazy Shade of Criminal,” which calls out the hypocrisy of a system that locks up blacks as those in power commit worse crimes with impunity, and tasks police with keeping the peace even as they fail to uphold the law themselves. The rap was a song of its time — the era of Rodney King — but unfortunately, it still rings true today, in the era of George Floyd. That continuity is not lost on Chuck D, who wrote: “We NEVER wished for times like these.”

Nevertheless, we know that protest can lead to the deeper, tougher work. As a tool for change, it may be one of the most effective ways to shake up a political system unwilling to listen to its constituents. William D. Ruckelshaus, who served as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s first administrator from 1970 to 1973, said in an oral history interview that public pressure was absolutely critical in the creation of the trailblazing federal agency.

“Public support only began to explode in the late 1960s. It led to the creation of EPA, which never would have been established had it not been for public demand. That I am absolutely certain of,” said Ruckelshaus during an interview conducted by the EPA History Program. “Public opinion remains absolutely essential for anything to be done on behalf of the environment. Absent that, nothing will happen because the forces of the economy and the impact on people’s livelihood are so much more automatic and endemic.”

A protester stands outside of Philadelphia’s City Hall on May 31, 2020. Jessica Kourkounis / Getty Images

Despite small but significant victories like these, the road ahead of us will be tough. For too long, we have been standing at a precipice, a place that Baldwin described as the center of a dreadful storm. And if we don’t do all in our power to change course, it will only get worse. It will be as the prophecy foretold in the black spiritual that Baldwin quotes at the end of The Fire Next Time — that on the final judgment day, “God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!” But if we do not falter in our duty, wrote Baldwin, “we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.”