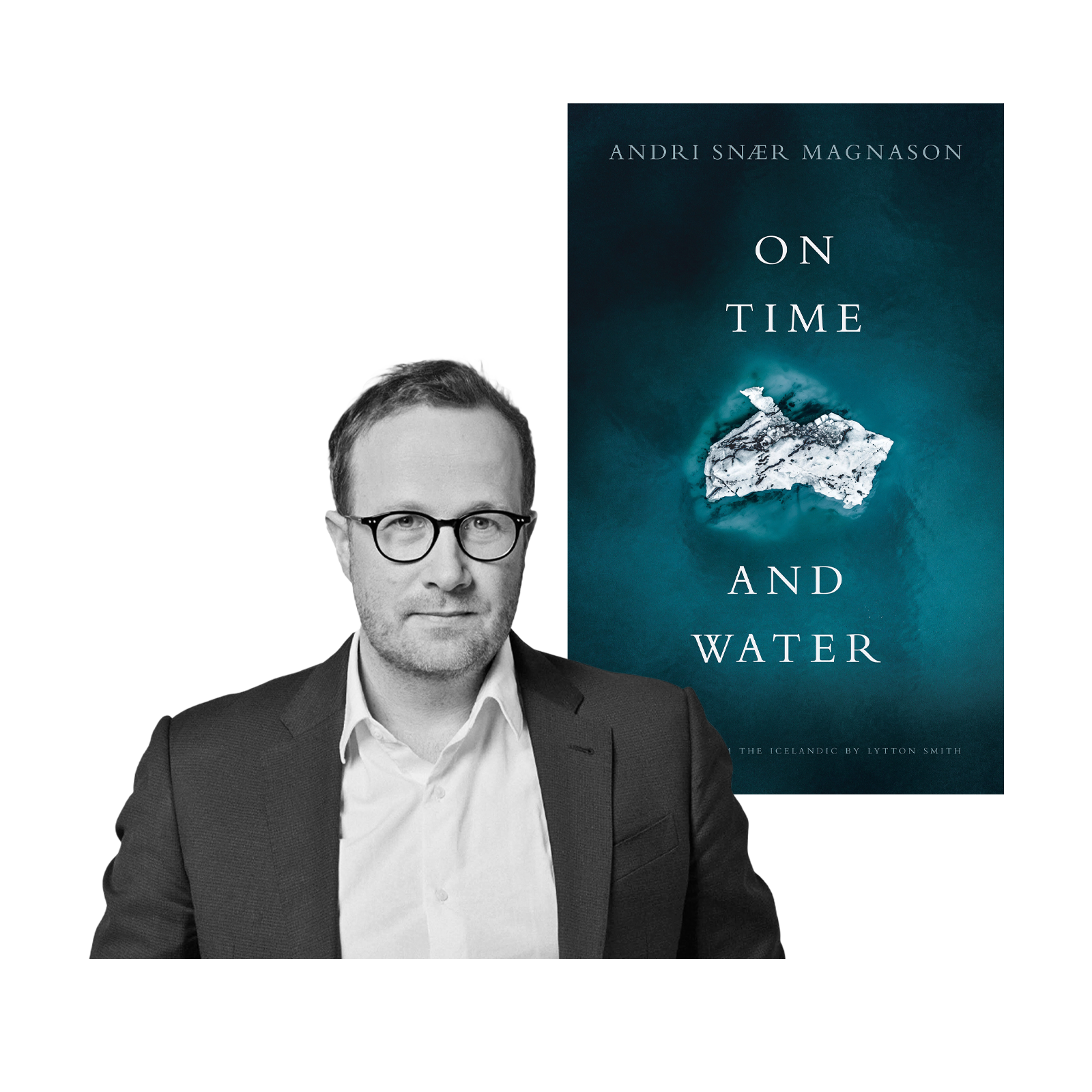

Andri Snær Magnason, the Icelandic writer and poet famous for writing a memorial to a dying glacier, has spent the last decade searching for the right words to capture a problem as big as the overheating planet. For most people, what climate change really means for humanity’s future hasn’t sunk in yet; otherwise, he reasons, everyone would be clamoring for action. How do you make that terrifying reality sink in faster, he wondered? Magnason’s book On Time and Water, recently released in the United States, is his attempt to answer that question.

During the years he spent gathering research for his book, the world changed dramatically. Countries signed the Paris climate agreement, renewable energy capacity quadrupled, and the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg rose to international fame. “What if the world will be saved before the book comes out?” Magnason found himself thinking. “It would be really disappointing if, you know, you spent 10 years writing a book, and then the problem is solved when it comes out,” he said over a video call, laughing.

Of course, that didn’t happen. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere is now rising at an even faster pace than when Magnason began looking for answers. On Time and Water, which topped the bestseller list in Iceland when it came out in 2019, has been translated into more than 20 languages. The U.S. edition, translated from Icelandic to English by Lytton Smith, came out this week. Drawing from Icelandic mythology, science, and his family’s history, Magnason gives the vocabulary of climate change new charge.

The book argues that despite all the warnings, people do not yet fully grasp the ramifications of a hotter planet. One problem, Magnason writes, is that the language of the climate crisis is still too new, too filled with jargon, too tainted by an obsession with economic growth.

“We see headlines and think we understand the words in them: ‘glacial melt,’ ‘record heat,’ ‘ocean acidification,’ ‘increasing emissions,’” he writes. “If the scientists are right, these words indicate events more serious than anything that has happened in human history up to now. If we fully understood such words, they’d directly alter our actions and choices. But it seems that ninety-nine percent of the words’ meanings disappear into white noise.”

On Time and Water deftly weaves a tapestry with threads that, at first glance, don’t appear to fit together. It includes transcripts of conversations between Magnason and the Dalai Lama and lessons on Icelandic mythology, history, and poetry, along with harrowing descriptions of what climate science forecasts for Earth’s future, reminiscent of David Wallace-Wells’ book The Uninhabitable Earth. Coral reefs face a death sentence; the ocean will acidify to inhospitable levels not seen for 50 million years; glaciers will melt away, drying up the water source for millions — all this happening during the lifetime of a child born today.

These frightening facts are embedded in something much easier to read about: stories of Magnason’s personal experience, along with his family’s and his country’s. The personal works as an entry point. He intuits that people want to read about Grandma, and once you’ve got readers warmed up, you can hit them with ocean acidification. Magnason recounts conversations with his daughter and tells stories of his Uncle John, a well-respected herpetologist who worked to save crocodiles. In one chapter, he tells the story of his grandparents’ honeymoon: a research expedition of Vatnajökull glacier — Europe’s largest, which covers 8 percent of Iceland. Their tent was nearly buried in a roaring snowstorm. (No, they hadn’t gotten cold, they told their bewildered 11-year-old grandson when he asked; they were newlyweds!)

At first, Magnason didn’t think he was qualified to write a book about the climate crisis. A scientist convinced him otherwise, telling him that without help from writers, scientific warnings were destined to go unheard. He began attending conferences where scientists spoke of the end of the world and everything they researched — glaciers, sea birds, coral reefs — in restrained tones, then drove off afterward and returned to their daily lives.

“Shouldn’t we have had tears in our eyes?” Magnason asks in the book, stunned by the detached way that a scientist studying coral reefs talked about his findings. “Even an expert on the subject didn’t seem to be able to breathe life into his research. He seemed unable to connect the deep experiences of diving and measuring the world’s coral reefs to other people’s imagination, to get across the sensations that arose from a knowledge of the impending death of everything he loved.” Maybe, he writes, scientists can’t fully understand their findings until others began to understand them.

To explain this concept, he turns to Icelandic history. In 1809, after Denmark had ruled Iceland for centuries, the Danish adventurer Jørgen Jørgensen declared Iceland “free” and “independent.” That’s not something that people in Iceland were asking for at the time, Magnason writes. The spirit of the French Revolution hadn’t spread to the island, and terms like “freedom” and “independence” hadn’t yet been translated or published there. Icelanders scoffed at Jørgensen, giving him the nickname the “King of the Dog Days,” and his experiment was short-lived. “He offered people freedom, but no one understood what he meant and so no one wanted to accept it,” Magnason writes.

The words used to describe the planetary crisis are just as new to vocabulary as the ones that Jørgensen used back then. Terms like climate change, global warming, and ocean acidification haven’t yet reached “full charge.” Magnason points to “ocean acidification,” the process by which the ocean’s pH is decreasing as its waters absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. Coined in 2003 by the atmospheric scientist Ken Caldeira, the word “is an example of a concept that has passed us by, although the phenomenon is one of the most significant changes in our planet’s chemistry and constitution over the last thirty to fifty years,” he writes. Magnason argues that “the forecasted end of the world was encrypted.” He points to a dense paragraph from a scientific report that spells out how the acidifying ocean will destroy marine life in the Arctic, cloaked in jargon like “aragonitic sub-saturation” and “RCP 6.0 scenario.”

Magnason has a knack for taking the everyday and turning it into something arresting and mythical. Airplanes, for example, are “metal dragons.” And those government officials who show up at climate conferences to haggle over emissions cuts? Call them “weather gods.” After all, the decisions they make affect whether glaciers survive, how powerful hurricanes become, and how much of the world’s coastlines will be sacrificed.

“History will ask, were these tragic gods that met and could not control their own inventions, like a Disney wizard — like everything went out of control?” he said. “Or were they wise gods that actually acknowledged that they had control over their own inventions and their own economies?”

If Magnason blames anything for the collective reluctance to acknowledge the scale of the threat humanity faces, it’s a shortsighted focus on economic growth. “Those who define the world based on money, industry, and production capacity have seemingly been spared from acquiring an understanding of biology, geology, or ecology,” he writes. “What’s fatal to the Earth and unsustainable for the future is hidden by the words ‘favorable economic outlook.’”

The book ends with a postscript, written last May when the pandemic kept people huddled inside, asking whether humanity will learn any lessons from the coronavirus-induced lockdowns. I asked Magnason what he thinks about that now. He posits that we have overestimated the effects on emissions in the short-term — after all, the dip seen in global carbon emissions last year is already being erased.

In the long-term, however, he believes that living through the so-called Anthropause could change how people respond to climate change. “I think the climate crisis will actually look easier after this than it did before,” he said. The way Magnason was raised, “it was almost unthinkable that any sector of industry could be shut down, just like this, over a weekend.”

But the Greta Thunberg generation has now seen the “pause button.” Governments really can shut down the economy if the situation is deemed dangerous enough. When this generation of young climate activists become the weather gods, they will know that button is there — and maybe they’ll press it.