The vision

You’re surprised to find yourself a little misty-eyed at this Harbor Day parade. The 60-foot float carrying the retired trash wheel — once an iconic waterfront fixture — glides joyously down the street. You remember visiting the wheel on school trips decades ago. Now, your kids will visit it in a museum.

It hasn’t been doing much for years now. Your city’s zero-waste strategies are some of the most ambitious in the country, and it shows. Still, you’ll miss seeing the snail-like structure out there, swimmers splashing around it — a reminder of all the work it took to get this harbor clean.

— a drabble by Claire Elise Thompson

The spotlight

Baltimore loves its local celebrities. I don’t think I can count the number of Edgar Allen Poe-themed bars and shops I’ve been to in my four years living here. Of course, there’s Natty Boh, the mascot for Baltimore’s favorite local beer, who sits atop the retired brewery tower winking all night at the city (and has a rumored romance with the Utz potato chip girl). And then there’s another googly-eyed persona, who, in addition to boasting over 20,000 followers on Twitter, offers a much needed practical solution to the trash problem in Baltimore’s harbor. His name is Mr. Trash Wheel. And he just celebrated his ninth birthday.

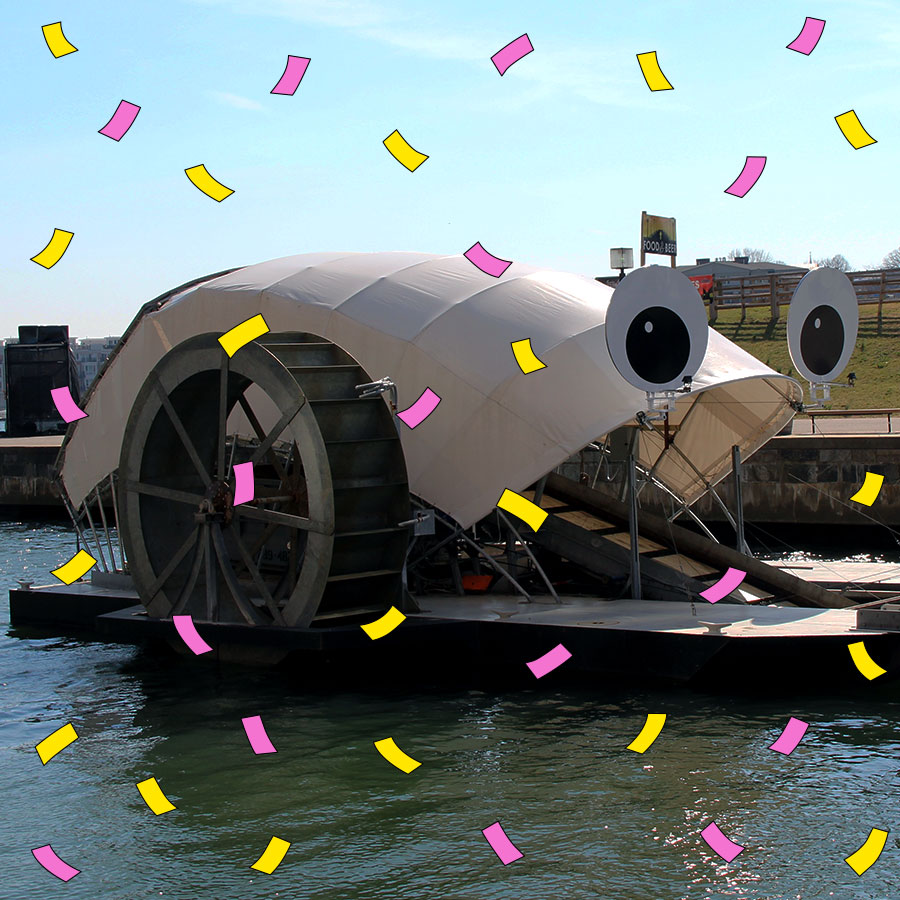

Mr. Trash Wheel awaiting a feast as a storm rolls in on his birthday. Claire Elise Thompson / Grist

Since he was installed at the mouth of Jones Falls in 2014, Mr. Trash Wheel and his growing trash-wheel family (now at four!) have collected over 2,000 tons of trash from the Inner Harbor. The wheels have inspired artwork, Halloween costumes, festivals, stuffed animals, and at least three local beers. He’s even been nominated for our Grist 50 list of emerging climate leaders.

Chelsea Anspach, communications manager for the Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore and the current voice of Mr. Trash Wheel on social media, describes his persona as excitable, puppylike, and never shaming of his human friends. “It pulls you in with this goofiness, and then you start to learn what Mr. Trash Wheel’s doing and how he’s helping the water here in Baltimore,” she says.

A homemade trash-wheel costume that wound up in my neighbor’s recycling bin in 2021. Claire Elise Thompson / Grist

The idea for the wheel originated with a man named John Kellett, who directed the erstwhile Baltimore Maritime Museum. Kellett was troubled by the amount of trash that pooled in the harbor, and particularly by the disparaging reactions from visitors he would overhear on his walks to work. He called the mayor’s office and was told, “We’re open to ideas.”

Kellett had grown up on a farm in Pennsylvania and recalled the functioning of an antique hay-pitching machine that his family had: As it was pulled through the field, the turning of the wheels powered a rake system that picked up hay and tossed it onto a wagon. “It occurred to me, why don’t we use the flow of the river as a power source to collect and remove the trash as it comes?” he says, adding that 90 percent of the trash washes in after heavy rains — which is also when the river flows fastest.

With funding from a local foundation, he built a prototype in 2008. “That one sort of flew under the radar for the most part,” Kellett says, “partly because of the way it looked, and partly because plastic pollution in the water wasn’t the hot topic it is now.” The original wheel resembled an old-style mill building on a floating barge. And it was a little undersized, Kellett says — but the technology seemed to work. While city officials were underwhelmed, the Waterfront Partnership, a local nonprofit dedicated to improving the health and accessibility of Baltimore’s urban waterfront, took an interest. The organization raised private and public funds to build a bigger, stronger version of the water wheel.

Kellett enlisted the help of an architect friend, Steve Ziger, to design a new model that would also gel better with the aesthetics of the area surrounding the harbor. Although the machine was initially faceless, it’s hard not to see its resemblance to a gaping maw. “He wanted to make the workings of it more observable,” Kellett says, “which I think was a great idea. Because I think when people see it and see what it can do, they understand the need for it better, and they’re inspired by it to become part of the solution.”

The first trash-wheel prototype, installed in 2008. Courtesy of Clearwater Mills

The new design in 2014. In addition to hydropower, Mr. Trash Wheel draws energy from 30 solar panels on his back that help move the booms and conveyor belt when the river is slow. Adam Lindquist

Shortly after the new-and-improved wheel was installed in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, Adam Lindquist, the Waterfront Partnership’s VP of environmental programs and an early supporter of the trash wheel, recorded a video of it gobbling trash after the first big rain event and posted it on Youtube. It received a million views over the course of a weekend.

“That was when we realized, OK, people are really excited about this idea. How can we build on it?” Lindquist says. “I went home, built some googly eyes in my basement, and put them up on Mr. Trash Wheel, named the device ‘Mr. Trash Wheel’ — and the rest is history.”

Adam Lindquist

Kellett admits to some initial concern about the plan to anthropomorphize the water wheel. He didn’t want people thinking the device was a gimmick and not a real asset to harbor cleanup. “It’s a serious machine doing a serious job,” he says.

But after seeing how Mr. Trash Wheel has endeared himself to Baltimoreans, and young people in particular, Kellett has embraced the googly-eyed persona as an ambassador for the health of the harbor and for avoiding single-use plastics. “I think that’s equally as important, if not more important, than the tons of trash that it picks up,” he says.

Mr. Trash Wheel has since been joined by several family members, and each trash wheel has a unique online persona. Professor Trash Wheel is a champion for women in STEM. Captain Trash Wheel is nonbinary and has a particular interest in birding — Baltimore’s first known bald eagle pair built their nest near Captain’s home in Masonville Cove. And Gwynda the Good Wheel of the West (named for her location in Gwynn Falls) naturally has witchy vibes. She is also the largest wheel of the bunch, and has smashed Mr. Trash Wheel’s record for the largest haul yet.

Trash pickup, whether it’s by hand or by conveyor belt, is a downstream solution to our single-use plastics problem. As Kellet himself says, “The trash wheels are a tool for treating the symptoms of the disease, but not a cure for the disease itself.” Maintenance teams currently don’t have the capacity to sort all of the potentially recyclable trash that ends up in the wheels’ 15 cubic-yard dumpsters. Instead, all of the refuse gets taken to the controversial Wheelabrator incinerator, along with around half the garbage from the city of Baltimore. The incinerator is the single largest pollution source in Baltimore, and has long been opposed by environmental justice groups.

But the devices also collect more than trash. All four wheels collect data on the waste they gobble. “We use photos of what we collect and that data to help educate our elected officials on the problems of trash and litter in our waterways,” says Lindquist.

In 2020, Maryland became the first state to implement a ban on foam takeout containers, and Baltimore County has since banned plastic bags as well. According to Kellett, the data from the trash wheels has been instrumental in lobbying policymakers to enact those laws.

And, Lindquist says, it also shows the effects of the laws in real time. “We know that there’s been an 86 percent reduction in foam containers in Mr. Trash Wheel since we banned them statewide,” Lindquist says. “So you can see the immediate impact that that ban is having on our local environment.”

A birthday card for Mr. Trash Wheel at a celebration at Pierce’s Park in Baltimore on Saturday, April 22. Claire Elise Thompson / Grist

At Mr. Trash Wheel’s ninth birthday celebration this past weekend, a new group of trash enthusiasts was initiated into the Order of the Wheel — a volunteer club with the air of a secret society. Anyone can join, but there is an application process, which involves completing challenges sent out by the Waterfront Partnership, like hosting or attending a community trash cleanup. One new inductee, Julia, sported a handmade robe and trash-wheel backpack (the latter was repurposed from her dog’s Halloween costume last year).

Julia in her A+ initiation robe and backpack. She said that she enjoys taking part in community service projects and events, and was inspired to join the Order because she feels litter cleanup is a tangible way to see the difference you can make in your community. Claire Elise Thompson / Grist

There were around 60 new inductees at the Saturday event, but the club extends far beyond Baltimore. Some 1,200 people are “pledging” this year from all 50 states, according to Lindquist and Anspach.

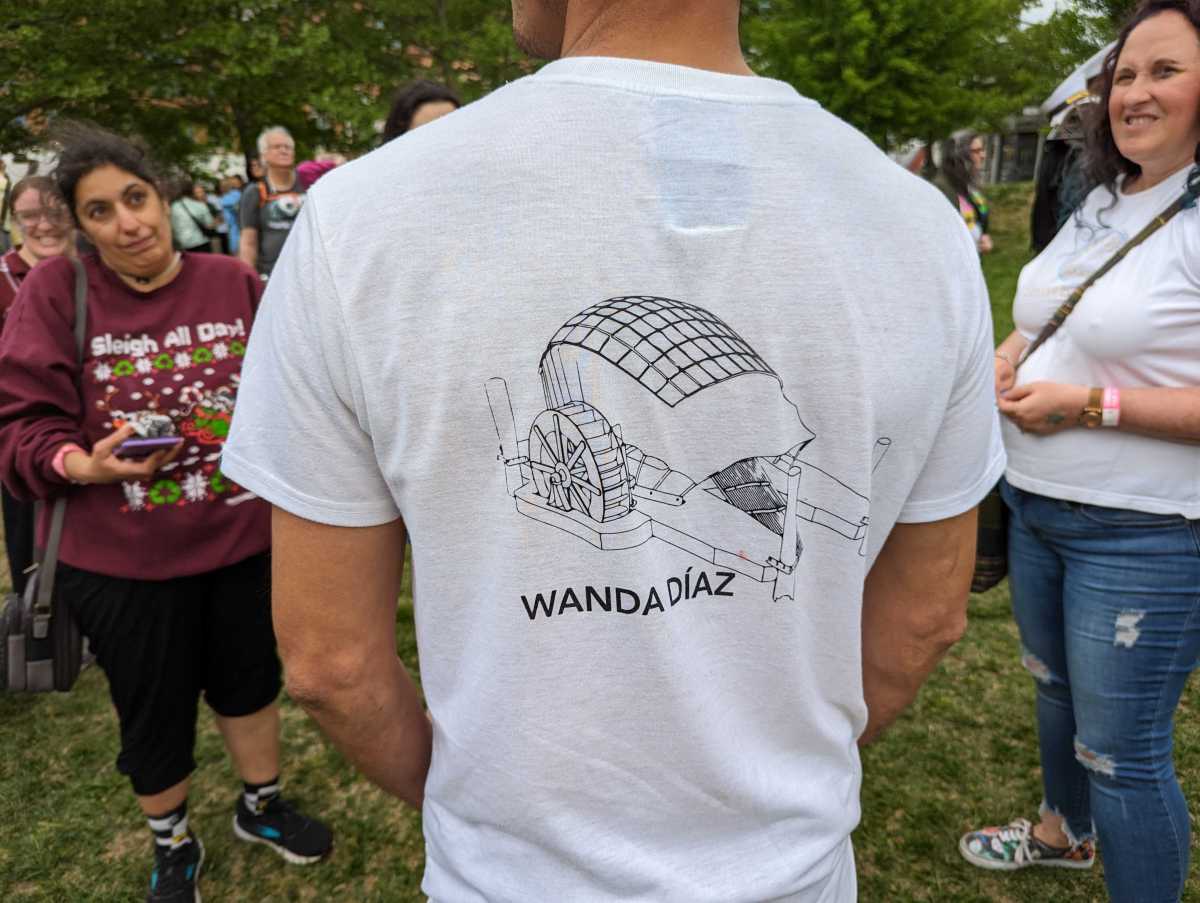

The idea for the wheels — nicknames and all — has also spread to other cities. Kellett and his team at Clearwater Mills, which runs the trash wheels through an operation agreement with the Waterfront Partnership, field requests every week to help install the infrastructure in new destinations. Last year, they traveled to Panama City to help local crews build the first international wheel, Wanda Díaz, on the Juan Díaz river.

Wanda already has her own merchandise — a T-shirt made of recycled plastic. Claire Elise Thompson / Grist

Kellett is hopeful that the success of these trash wheels will lead to additional policy changes as well as behavior changes that will ultimately allow Mr. Trash Wheel and his family to retire. The idea is even baked into the oath that new Order of the Wheel members take: “From this hour henceforth, I will join the fight to rid trash from land and sea, until the trash wheels have nothing to eat and the ocean is clean.”

— Claire Elise Thompson

NOTE: In last week’s newsletter, about the four-day workweek, I misspelled Tommy Wiedmann’s last name. My sincerest apologies!

More exposure

- Read: more about the history of Mr. Trash Wheel and the spreading of similar projects (The New Yorker)

- Read: about progress toward the goal of making Baltimore’s harbor swimmable (The Baltimore Banner)

- Read: about plans to install a trash wheel in Newport Beach, California — the first on the West Coast (The Orange County Register)

- Read/Watch: a local news segment about the Order of the Wheel (CBS Baltimore)

On our horizon

It’s time for another Looking Forward book club! By popular demand, our next read will be 🥁… Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer!

The gathering will be Wednesday, June 7, at 6 p.m. Eastern. RSVP here.

We’re super excited to read and discuss this gorgeous book with all of you. And, with gratitude to Milkweed Editions, we’re giving away five copies! RSVP by next Thursday, May 4, and let us know if you’d like the chance to win a free book.

A parting shot

Saturday’s event in Baltimore also featured live snakes on display, courtesy of an education and conservation org called Eco Adventures. Why, you might ask? Well, Mr. Trash Wheel’s most famous catch ever was a live ball python that the team rescued from his conveyor belt with the help of a curator from the nearby National Aquarium. It was presumed to be an escaped or abandoned pet. Since the python incident, snakes have been a central part of the Mr. Trash Wheel lore (the first trash-wheel beer was the Lost Python Ale from Peabody Heights Brewery).