The 2010 failure of the Senate to pass cap-and-trade legislation is a scar the environmental movement tries to ignore but can’t stop examining. It sits there, barely healed, still painful — a reminder of the lost promise of a new president and a brief House majority.

Harvard University political scientist Theda Skocpol has released a long, robust assessment of what went wrong in the political fight [PDF]. It’s a detailed document that analyzes the politics of environmental policy leading up to the fight and in the years following, drawing direct contrast with the push for healthcare reform. Why that effort succeeded — barely — at the same time that cap-and-trade failed is interesting.

Skocpol’s thesis for why cap-and-trade failed can be simplified to a few points: failed organizing efforts by advocates for the policy, an attempt to craft legislation behind closed doors at a moment that demanded transparency, and (of course) massive shifts in public opinion due to the concerted efforts of opponents of action.

It’s that first point that is perhaps the most instructive, if I may betray my prejudices. Skopcol notes that environmental groups shifted focus away from the grassroots after winning key environmental protections. “Once those laws and federal regulatory bureaucracies to enforce them were in place,” she writes, “the DC political opportunity structure shifted — and so did the organization and focus of environmental activism. Big environmental organizations headquartered in Washington DC and New York expanded their professional staffs and became very adept at preparing scientific reports and commentaries to urge the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) onward.”

Moreover, the organizations focused on responding to public opinion more than shaping it.

This division of labor in the cap and trade effort — insiders work out legislation, pollsters and ad-writers try to encourage generalized public support — reflects the way most advocates and legislators in the DC world proceed nowadays. “The public” is seen as a kind of background chorus that, hopefully, will sing on key. Insiders bring in million-dollar pollsters and focus-group operators to tell them what “the public” thinks and to try to divine which words and phrases they should use in television ads, radio messages, and internet ads to move the percentages in answers to very general questions. …

Professionally run organizations and DC insiders take national surveys too seriously. A lot of what they measure amounts to nothing more than momentary shifts in aggregate opinion, swayed by events, elite debates, and the latest television coverage. Public sympathy for a cause can be broad but very shallow — and that has been true for decades now with U.S. national public sympathy for environmental priorities. Environmental organizations are investing way too much money in polling operations, and spending too much time imaging which phrases they should use in messaging campaigns disconnected from organized networks.

This led advocates to talk about “green jobs,” “threats to public health,” and the need to “reduce dependence on foreign oil to bolster national defense,” anything but the threat of global warming and catastrophic climate upheavals.” Which, as we’ve noted before, provides a disincentive for evoking the sort of passion that inflames public opinion on an issue.

Meanwhile, the election of Barack Obama and the sinking economy had done plenty to inflame opinion among the opposition in 2010 — though it started well before that.

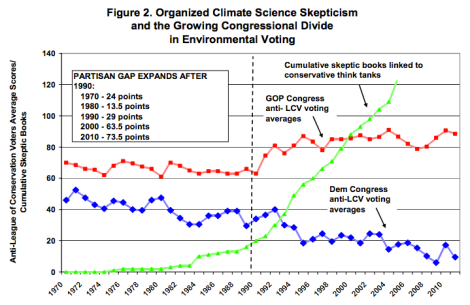

For two decades after 1990, the two major U.S. political parties pulled far apart on environmental issues, and particularly on global warming. Democrats became increasingly committed to taking action about carbon emissions they understood to be spurring global warming, while conservative elites and GOP legislators turned to denial and opposition. Matters arrived at a politically pivotal juncture in 2006 and early 2007, with a definitive U.N. report and Al Gore’s influential documentary “An Inconvenient Truth.” Public opinion shifted toward viewing global warming as a serious threat that government should address. In response, opponents of carbon-capping took active steps to heighten popular skepticism and change political calculations. Their efforts started to pay off in 2007, months before the economy plunged into recession in 2008 and well in advance of Obama’s move into 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Thereafter, Tea Party mobilizations finished the job, putting GOP politicians on notice that compromise on environmental issues is unacceptable to ultra-conservative funders and vigilant primary voters.

The Tea Party sat atop a growing, powerful push to undermine science.

To get around academia, U.S. anti-environmentalists updated methods that had worked before in the fight against liberal welfare policies and in the fight to stave off regulation of tobacco as a carcinogen. They used non-profit, right-wing think tanks to sponsor and promote a cascade of books questioning the validity of climate science; and they pounced on occasional dissenters in the academic world, promoting them as beleaguered experts. A “counter-intelligentsia would be deployed to label mainstream academia as “leftist” and put forth a steady stream of books, reports, and policy briefs, not only to inform policymakers and their staffers directly, but also to induce media outlets to question the motives of reformer and present the science of climate change as, at best, controversial.

… Those Tea Parties in turn sustained grassroots public agitation against the priorities of the Obama administration and the Democrats in Congress — with health care reform and cap and trade among the chief targets of their wrath. In addition, Tea Party forces set out to purify and discipline the Republican Party, to make sure that GOP officeholders would never compromise with the hated Obama and Democrats. The “Tea Party” efforts came simultaneously from below — from local Tea Parties and the very conservative-minded voters who made up about half of all Republican-identified voters — and also from above …

While this backlash was growing, “organizing” efforts by proponents were happening almost only from above.

Both Gore’s Alliance and Tewes’s Clean Energy Works claimed to have airlifted state organizers into dozens of swing states to work on media-events at crucial legislative junctures. But most of their tens of millions of dollars in messaging resources went into mass persuasion advertisements, especially on television. And how effective were the ads? They rarely identified heroes or enemies in specific ways — beyond tentatively criticizing generalized “polluters” — and they maintained a lofty nonpartisan stance well above the level of any policy specifics, offering very general calls for Americans to act together to address sketchily defined problems caused by climate change …

The opponents did a better job of scaring citizens than the proponents did of arousing enthusiasm for whatever it was they were trying to get through Congress.

Skocpol’s takeaway, then, is to build real organizing, using policy fights as needed. But it will take time, barring some massive shift in public opinion.

The political tide can be turned over the next decade only by the creation of a climate-change politics that includes broad popular mobilization on the center left. That is what it will take to counter the recently jelled combination of free-market elite opposition and right-wing popular mobilization against global warming remedies. However, in stating this conclusion, I want to be clear about what I am not arguing. Some of the environmental left seem to be calling for a politics that gives up on legislative remedies — and avoids altogether the messy compromises that fighting for carbon-capping legislation would require — in favor of a turn toward pure “grass roots” organizing in local communities, states, and institutional settings such as universities. Of course, environmental activists can encourage (and already have achieved) very valuable steps in the states — such as California’s new effort to raise the cost of greenhouse gas emissions. And both professional advocates and grassroots activists can prod businesses and universities to “go green” in purchasing decisions and investment choices.

These kinds of efforts add up over time — and they may in due course prompt corporate chieftains to support economy-wide regulations, if only to level the playing field and create more predictability about business costs and profit opportunities. Some day, the national Republican Party might again start listening to such business leaders more closely than to right-wing ultra-ideologues. But rescuing the GOP from its destructive radicals will take time — not to mention more courage from nonTea Party Republicans, who must rouse themselves to do that job. …

Whatever happened years ago, “bipartisanship” in today’s Washington DC on environmental policymaking is not going to emerge from additional efforts at insider bargaining — not given the stark polarization of the parties, with so many Republicans now wary of compromise or tilting off the edge of the far ideological right. …

The only way to counter such right-wing elite and popular forces is to build a broad popular movement to tackle climate change.

What Skocpol proposes is hard, expensive work, fielding teams in diverse areas of the country focused on strategic power-building. It’s a forgotten art, one that can be goosed by media enthusiasm but not one that can be maintained by it. And, unfortunately, it’s not one that can be recreated by organizing organizations.

Whether or not environmental groups can learn the lessons that gave them that scar is an existential one. Not only for them. For all of us.

Read more on Theda Skocpol’s report on the failure of cap-and-trade: responses from Bill McKibben, Eric Pooley, Joe Romm, Mark Hertsgaard, and Mike Tidwell; three (count ‘em: one, two, three) posts from David Roberts; and a followup post from Skocpol herself.