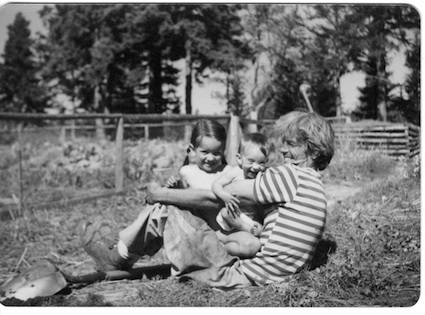

Portrait of the farmer as a young man: Eliot Coleman with children, circa early 1970s.Reprinted with permission from Melissa Coleman. I’m not sure exactly what it means to play a cameo role in a family memoir exploring the roots of today’s food movement; but certainly it makes you keenly aware of how quickly the years are piling up. I’m referring to the tale of my brief, but apparently significant, role in helping launch organic farmer and author (and occasional Grist contributor) Eliot Coleman toward fame, chronicled in the new memoir by his daughter, Melissa, This Life Is in Your Hands, recently reviewed quite favorably in The New York Times. (Grist’s Tom Philpott recently interviewed Eliot Coleman here.)

Portrait of the farmer as a young man: Eliot Coleman with children, circa early 1970s.Reprinted with permission from Melissa Coleman. I’m not sure exactly what it means to play a cameo role in a family memoir exploring the roots of today’s food movement; but certainly it makes you keenly aware of how quickly the years are piling up. I’m referring to the tale of my brief, but apparently significant, role in helping launch organic farmer and author (and occasional Grist contributor) Eliot Coleman toward fame, chronicled in the new memoir by his daughter, Melissa, This Life Is in Your Hands, recently reviewed quite favorably in The New York Times. (Grist’s Tom Philpott recently interviewed Eliot Coleman here.)

Some background: As a Wall Street Journal reporter in 1971, I wrote a front-page profile of a middle-class family living off the land in coastal Maine — the family of Eliot Coleman, including his then-2-year-old daughter Melissa. That profile, headlined, “The New Pioneers,” was one of the WSJ‘s best-read features ever to that time, so popular that front page editors encouraged me to revisit the Colemans and do another piece two years later (sorry, that one seems to be unavailable online).

It was a major event for me personally — not only experiencing the Colemans’ vegetarian and no-electricity lifestyle, but meeting and getting to know the original trailblazers in the living-off-the-land movement, Helen and Scott Nearing; the authors of the classic Living the Good Life, who lived just down the road from the Colemans.

I lost touch with the Colemans after doing those profiles, though I did read articles here and there about Eliot’s own increasingly successful writing career, as one of the world’s foremost experts on growing organic foods year-round in hostile climates like in Maine. Contained in some of the articles I read were snippets suggesting family problems … but then, I figured, who doesn’t have family issues?

I reconnected with the family when Melissa contacted me a year-and-a-half ago to tell me about her upcoming book, and to request an interview to capture what I remembered about visiting her family in 1971 and living in a tiny trailer while reporting my story. It turned out that my initial WSJ article was a watershed event for the family, leading to a huge influx of both tourist and hippie visitors to the family’s isolated outpost on Maine’s Cape Rosier, and eventually to Eliot becoming a celebrity farmer.

Needless to say, it’s kind of strange to read now in a memoir the remembrances of my initial visit and the family’s impressions of me. “He had lived only in Chicago, New York, and Boston, so our lifestyle was an especially exotic contrast to his own. Quiet and easy to talk to, the young reporter adapted without complaint to the difficulties of using the outhouse and eating our vegetarian food, though he secretly thought the goat’s milk tasted of the barnyard … ” (I suppose that was my first exposure to raw milk.)

Eliot’s then-wife, Sue, expressed feelings of foreboding about my visit, noted Melissa. In a diary, Sue stated, “I realize now that the experience with the reporter was an unfortunate one. He was like an intrusion, making me feel uneasy and paranoid the three days he was here.” Melissa reports. She adds, though: “despite Mama’s fears, it turned out to be a favorable profile.” And more significantly: “The article … was a messenger of change, as more and more people became interested in a simpler way of life — people who would seek us out in droves … “

Some of the change was positive, as volunteers showed up, ready to pitch in and reduce the huge workload on Eliot and Sue. Some was stressful, putting the couple ever more under outside scrutiny. The intrusions were especially difficult for Sue, who was by nature a very private person. The breaking point occurred with the drowning of Melissa’s younger sister, Heidi, in a pond on the farm in 1976.

Aside from the fact that the tragedy tore the family apart, it also forced Melissa, in the course of writing the book, to confront larger issues associated with the family’s unusual lifestyle. Indeed, the entire situation carries important messages for today’s emerging class of professionally trained and city-raised young and middle-aged farmers. I won’t reveal any more about the book, except to say that it is an absorbing read that intelligently arrays the romanticism of living off the land against the emotional challenges of moving off the grid.