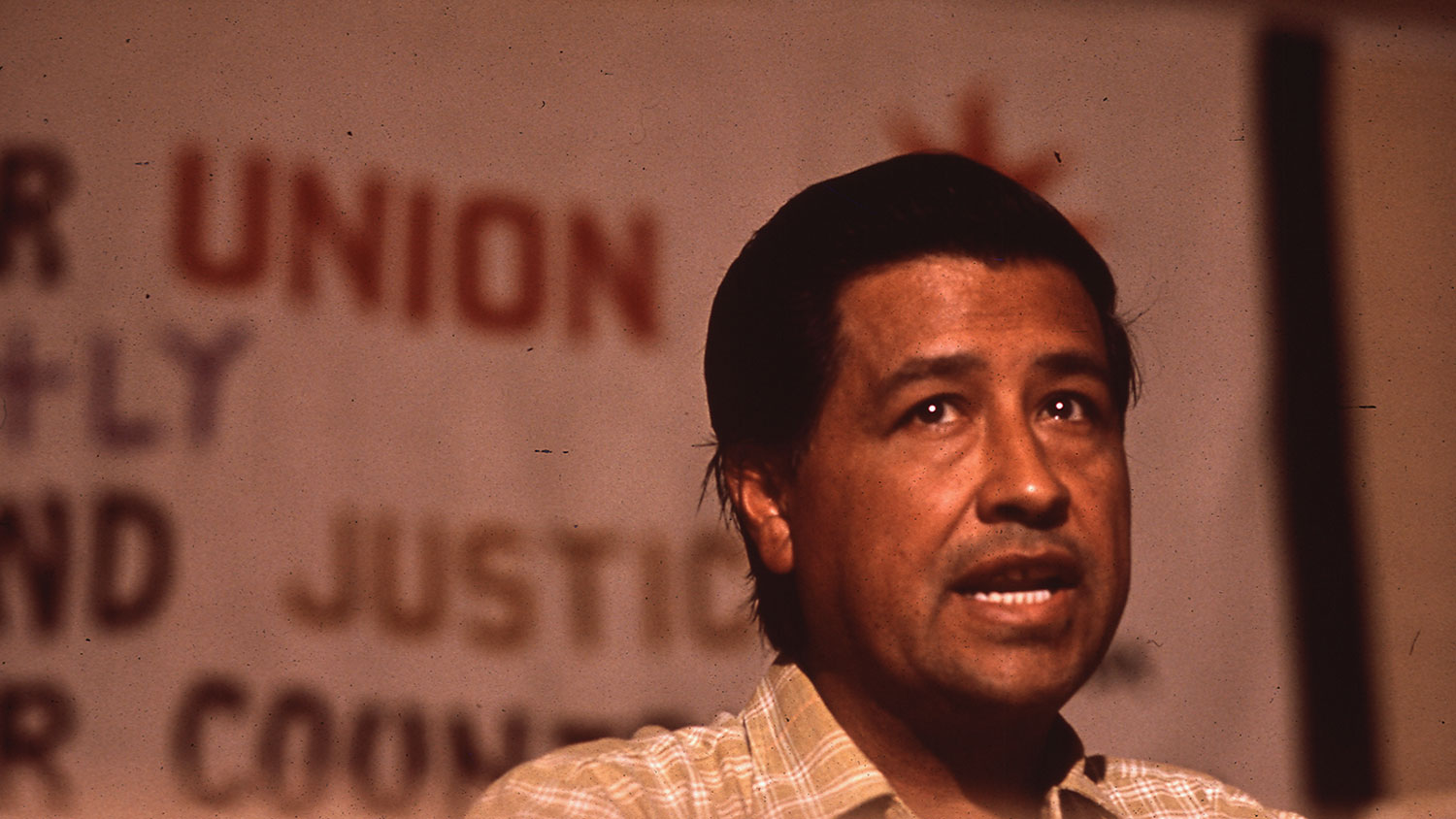

The irony of nonviolent resistance is that it needs violence to be effective. The spectacle of mobs, deputized and otherwise, billy-clubbing people as they turn cheeks until they run out of cheeks to turn, tends to assault the consciences of those observing. Gandhi understood this, as did his acolytes Bayard Rustin and Rev. James M. Lawson Jr., who both brought Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to understand it. A young Chicano farmworker named Cesar Chavez also understood this, and made it a central tenet of his social justice work in the 1960s.

Today, many Americans are celebrating Chavez’s birthday to commemorate his hard work in organizing some of the hardest workers in the nation: farmworkers. But 22 years after his death, those who toil in the agricultural fields are still under assault from unjust laws and toxic chemicals.

Chavez knew from his own experience that farmworkers were among the most socioeconomically and physically vulnerable laborers in the nation’s workforce, who also suffered from having the fewest legal protections. In 1965, Chavez helped lead Chicano laborers in the National Farm Workers Association to join Filipino farmworkers in the Agricultural Worker Organizing Committee in a workers’ strike against their grape grower bosses in Delano, Calif. This led to the formation of the United Farmworkers Organizing Committee, later named the United Farm Workers of America (UFW), the first successful union for farmworkers.

The UFW not only achieved the first major collective bargaining deal with the powerful grape companies in 1969, but also helped the mostly immigrant farmworkers understand in a visceral way that they have rights as workers, residents, and as human beings. Here’s Rick Tejada-Floreshat on what they won in that deal:

There was an end to the abusive system of labor contracting. Instead, jobs would be assigned by a hiring hall, with guaranteed seniority and hiring rights. The contracts protected workers from exposure to the dangerous pesticides that are widely used in agriculture. There was an immediate rise in wages, fresh water, and toilets provided in the fields. The contracts provided for a medical plan, and clinics were built in Delano, Salinas, and Coachella.

It was a hard-earned victory that followed years of striking and marching farmworkers getting routinely attacked by white workers, often with police help. It wasn’t uncommon for white farmers to spray pesticides directly into farmworkers’ faces. Violence continued even after the 1969 deal, when the grape companies allowed the Teamsters union to capitalize off of the farmworkers’ deal. The mostly white Teamsters workers viciously attacked Chicano and Filipino farmworkers — who now had fresh water and better wages, but still didn’t have equal protection under the law — over territorial disputes.

In 1975, California passed the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which was supposed “to ensure peace in the agricultural fields by guaranteeing justice for all agricultural workers and stability in labor relations.”

But 40 years later, there still is little peace for migrant farmworkers, who remain among the least protected class, and whose lives are at the mercy of the political winds. And while no one is spraying pesticides in their faces anymore, they remain exposed to chemicals linked to cancer and other health disorders at a much higher rate than the average worker.

The Department of Labor has worked to address these protections, as has the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, despite its spotty history on pesticide use. Last year, the EPA proposed its new Farm Worker Protection Standards, which include, for the first time, a prohibition on children under 16 handling pesticides (this has been acceptable all these years?). Farmworker justice groups such as the Pesticide Action Network, UFW, Earthjustice, and the Migrant Clinicians Network are in D.C. today to deliver bundles of signed petitions urging EPA to finalize the new rules.

The harmful effects of pesticides are visited not just upon teenage farmworkers, but also on farmworkers’ children who don’t even hit the fields. Winds carry the toxic fumes of pesticides, what’s called “pesticide drift,” from the farm fields to the homes and schools of mostly Latino families. As much as 10 percent of agricultural pesticide sprays drift from crop areas, and about 70 million pounds of pesticides are lost to the winds, according to the EPA.

A report released by Californians for Pesticide Reform this month explains how fumigants like chloropicrin — gases once used as weapons in World War I — have been linked to cancer, reproductive health problems, cognitive development problems, and groundwater contamination. Reads the report:

From 1999 to 2012, fumigants drifting from fields in California have poisoned at least 1,641 workers and community members with symptoms of burning eyes, nausea, headaches, asthma attacks and throat irritation. These reported poisonings are only the tip of the iceberg, as most pesticide-related illnesses likely go unreported.

This is a different kind of violence enacted upon migrant worker families, especially the children — the most vulnerable of the most vulnerable. The EPA has taken steps to address pesticide drift and fumigants, some of which are found in greenhouse gases. Last October, the agency launched a voluntary “drift reduction technology” program, which “encourages manufacturers” to test and label any equipment they use for drift reduction. The operative word there is “voluntary,” though, which is why PAN staff scientist Emily Marquez says the program “falls flat.”

“Manufacturers are under no obligation to adopt new technologies or adapt to new information,” said Marquez. “Updates to drift reduction technologies should be mandatory, which would result in real-world reductions of spray drift in agricultural communities.”

Farmworkers have never enjoyed equal protection in America, in part because agricultural workers are treated as a separate class from other workers. When New Deal programs were created in the 1930s to extend new rights and protections to workers, the house-service and agricultural industries were excluded specifically because they employed people of color. President Franklin D. Roosevelt needed the votes of Southern Democrats — at the time the gatekeepers for Jim Crow policies — to pass New Deal legislation, and so he made the Faustian bargain of exempting workforces filled with minorities so the bills would pass. Ira Katznelson writes in his book Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time how Roosevelt and Congress accomplished this, through:

a decentralization of responsibility that placed administrative discretion in the hands of state and local officials whenever possible, a recognition in law of regional differentials in wage levels, and the exclusion of maids and farmworkers — fully two-thirds of southern black employees — from key New Deal programs.

While much of the bigotry there was aimed at disempowering black workers, immigration policies passed from the 1924 Immigration Act to the 1941 Bracero Program ensured that Asian, Filipino, Chicano, and Latino migrant farmworkers would have even less rights and protections. Chavez understood this, and knew this would make organizing migrant farm labor a difficult, if not impossible task. It’s hard to have an effective strike when laws allowed companies to literally farm in more labor from other countries to replace the striking workers.

It all adds up to a cocktail of racial, ethnic, economic, and environmental violence that still today plagues farmworkers, their children, and children who have the misfortune of living near these farms. And yet, Chavez maintained a stance of nonviolence throughout the 1960s, even going on hunger strikes in hopes of quelling the violence — at least until 1970, when he made this statement that suggested a more nuanced take:

We maintain that you cannot really be effective in anything you are doing if you are so loaded with violence that you cannot think rationally about what you have to do. We know that violence works. I’m not going to say it doesn’t work. Total violence still works and is working many places.

Today, we see the violence of pesticide drift in the health symptoms of the people it affects. We see how migrant workers have been exploited as they labor to help get food from the farms to our tables. These examples are evidence of how exactly violence works, by maintaining power and wealth for a few at the expense of people’s lives and the life of the planet. We may have never spotted this violence if not for the work of Chavez and his Filipino and Chicano colleagues in the fields.