This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In the journal from his legendary 1869 expedition down the Colorado River, explorer John Wesley Powell called the remote Tavaputs Plateau in Eastern Utah “one of the stupendous features of this country.” The one-armed Civil War hero marveled at the Wasatch Mountains soaring above the Uinta Basin, the canyons carved by the Green River thousands of feet below, and the Uinta Mountains to the north, where, he wrote, “among the forests are many beautiful parks.”

Much of that vista remains unchanged, except that now it’s blanketed with thousands of oil and gas wells, and in the winter, a thick layer of smog that constitutes some of the worst air pollution in the country. Since the first significant oil well was drilled there in 1948, the Uinta Basin has become home to some of the most productive oil and gas fields in the mountain west. Its relatively modest output of at most about 90,000 barrels of oil a day contrasts dramatically with places like the Permian basin in New Mexico and Texas, which will pump out more than five million barrels of oil a day this year.

But what the Uinta Basin holds is immense potential.

Locked inside the basin’s sandstone layers are anywhere between 50 and 321 billion barrels of conventional oil, plus an estimated 14 to 15 billion barrels of tar sands, the largest such reserves in the United States. The basin also lies atop a massive geological marvel known as the Green River Formation that stretches into Colorado and Wyoming and contains an estimated three trillion barrels of oil shale. In 2012, the U.S. Government Accountability Office reported to Congress that if even half of the formation’s unconventional oil was recoverable, it would “be equal to the entire world’s proven oil reserves.”

Wildcat speculators, big oil companies, and state officials alike have been salivating over the Uinta Basin’s rich oil deposits for years, yet they’ve never been able to fully exploit them, for one basic reason: all those mountains that enchanted Powell 125 years ago.

Even today, only two main roads link the oil fields to refineries in Salt Lake City, and they’re often two-lane highways with steep grades that can be nearly impassable in the winter. For decades, Utah officials have been hoping to remedy this problem, primarily by trying to build a railroad to service the mineral-rich basin, which also holds large deposits of phosphate, gilsonite (a form of asphalt), coal, and, potentially, rare earth minerals. All of those efforts have failed to get traction — until now.

In December, the federal Surface Transportation Board, or STB, signed off on a plan to build an 88-mile railway from the Uinta Basin to a rail terminal about 100 miles south of Salt Lake City. The railway, devoted almost exclusively to transporting oil, could allow oil production in the basin to quadruple at a time when scientists say the world has less than a decade to wean itself from fossil fuels or face irreversible catastrophic impacts from climate change. “Investing in new fossil fuels infrastructure is moral and economic madness,” United Nations secretary general, António Guterres, said in April when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its most recent report. “Such investments will soon be stranded assets — a blot on the landscape and a blight on investment portfolios.”

The Uinta Basin Railway will be the largest freight rail infrastructure project in the U.S. since the late 1970s, and promoters say it will bring jobs to a depressed rural area while helping liberate the U.S. from reliance on foreign oil.

“This has long been an area in need of rail,” says Mike McKee, a former Uintah County commissioner who is retiring this spring as the executive director of the Seven County Coalition on Infrastructure, a quasi-governmental organization that has been orchestrating the railway. “We don’t have a freeway into the Uinta Basin. It’s just that we have high mountains around us, so it’s been challenging.” With the railway, he told me in an interview in February, “we’ve found a way to do this that’s viable.”

McKee is backed by Utah’s entire political establishment — everyone from Republican Governor Spencer Cox to Republican Senator Mitt Romney to local county commissioners — in supporting a project that picked up steam during the Trump administration. Now, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Republicans are pushing the Biden administration to expedite approval of the railway as a way of increasing domestic oil production and reducing reliance on Russian oil. The railway needs permission to traverse part of the Ashley National Forest, which Biden’s U.S. Forest Service chief tentatively approved in October. But the decision is not yet final, and Utah officials have been pressuring the administration to finish the job so construction can get underway this year.

“[Y]our administration must end its fight against public land energy development in Western states, including Utah,” Utah Governor Spencer Cox wrote in a letter to Biden on March 7. “We need support for the Uinta Basin Railway.” Republican Senator Mike Lee, who met with the Forest Service at the end of March to discuss the railway, has been even more critical. “Biden would rather flirt with mullahs in Iran and the despot in Venezuela than help places like the Uinta Basin,” Lee told an eastern Utah radio host in late March. “Mr. Biden, approve this project. We need it now.”

Environmentalists, however, warn that the railway could have immediate and long-term catastrophic effects by facilitating an increase in oil production that could pump as much as 53 million pounds of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere annually. Construction will harm big game migration areas and disrupt critical at-risk breeding areas of the greater sage grouse. It will cut through at least 12 miles of inventoried roadless wilderness areas. And during a time of extreme drought, the construction will impact more than 400 streams, many within the critical watershed of the Colorado River, which provides drinking water to 40 million people in the West.

“We’re seeing the Uinta Basin as sort of a test case as to whether the Biden administration can walk the talk,” says Deeda Seed, a senior public lands campaigner with the Center for Biological Diversity in Salt Lake, which in February filed a lawsuit in federal court to block the railway. “If they can’t get it right here in terms of their ability to stop climate-damaging, Utah-based projects, we’re screwed.”

One crisp sunny day in October, I decided to drive the planned railway route. I grew up in Utah, but I’d never traveled out that way and I was curious to see what was at risk. From Salt Lake, I headed south and picked up Highway 6, which runs along the Price River up a spectacular, rugged canyon, to the tiny town of Kyune. That’s where the Uinta Basin railway would connect to the national rail network that would transport basin oil to Gulf Coast refineries and beyond.

From Kyune, I bumped along the rutted Emma Park Road, where the railway would skirt the edge of Indian Head ranch, an expansive 10,000-acre private elk hunting reserve and state cooperative wildlife management area. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been working here to improve the habitat for the sage grouse, whose critical mating grounds lie within a mile of the proposed railway route.

Just past the ranch, I saw my first pumpjack, gently dipping like a bird as it extracts oil from a well lacking sufficient pressure to force it to the surface. It seemed surprisingly graceful for an instrument of planetary destruction. In this vast, empty landscape, the only other notable landmark for miles appeared when I headed north onto Highway 191 and passed a solitary monument built in 1918 by prison inmates as a tribute to Simon Bamberger, the state’s first and only Jewish governor.

Highway 191 is an official state scenic byway, but instead of many leaf peepers or RV enthusiasts on my drive, I encountered a steady stream of oil tankers coming the other way. The trucks are both a unique feature and a significant hazard of Utah’s oil industry, and one of the driving forces behind the railway proposal. Here’s why: Most U.S. oil is transported via pipelines. But Uinta Basin oil is mostly a yellow, waxy crude that must be heated above 115 degrees Farenheit to keep it from solidifying. As a result, basin oil is shipped in 250 heated tanker trucks to five Salt Lake refineries every day, where it’s converted to gasoline, jet fuel, and propane before being shipped throughout the West.

The scourge of Utah commuters, oil trucks clog up freeways and barrel down the steep and often snowy mountain roads, where they occasionally crash and burn. In the winter of 2017, a semi carrying 11,000 gallons of oil up Parley’s Canyon hit another truck and burst into flames, killing one of the drivers and closing the road for hours. The following year, another tanker crashed along Highway 6 and spilled hundreds of gallons of oil into the Price River. County officials in the Uinta Basin predicted in March that after oil prices jumped to $100 a barrel after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the number of tankers on the road could soar to 400 a day in the coming months.

A decade ago, the Utah transportation department began researching the feasibility of a Uinta Basin railway after a state study concluded that the region would lose at least $30 billion in economic benefits and tens of thousands of jobs over 30 years without more viable transportation options for the basin’s waxy crude.

To help advance this goal, in 2014, a group of counties in eastern Utah banded together to develop regional infrastructure projects. Now known as the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition, its leadership consists of elected commissioners from the state’s most significant fossil fuel producing counties — local governments not famous for their environmental sensitivity or fiscal responsibility. (Last year, for example, the Uintah County Commission spent half a million dollars in federal pandemic relief funds to build a snow tubing park.)

Among the coalition’s former chairmen is Phil Lyman, a former San Juan County commissioner and well-known critic of federal land management. Lyman was arrested in 2014 for leading a protest of about 50 ATV riders up Recapture Canyon, a Native American archeological site that the Bureau of Land Management had closed to motorized vehicles. He was joined by Ryan Bundy, son of the Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy, who only a month earlier had engaged in an armed standoff with the BLM. Lyman was convicted of misdemeanor trespassing and sentenced to 10 days in jail — a sentence that did not prevent him from being elected to the Utah legislature in 2018. President Donald Trump pardoned Lyman in 2020 just before leaving office.

For all their animosity towards the federal government, leaders of the infrastructure coalition nonetheless sought funding for the railway from the state’s Permanent Community Impact Fund Board, or CIB, which administers what might be considered a slush fund of royalties from federal oil and gas leases. State and federal law require the board to invest in projects for the public good, like sewer lines and new fire trucks, to mitigate the negative impact of extractive industries on rural communities. But conveniently for the Uinta Basin railway enthusiasts, the CIB has been led by many of the same people who also served on the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition board, including its retiring executive director Mike McKee.

The CIB has spent millions in public money, often in no-bid contracts, to subsidize roads and other projects that mainly benefit the fossil fuel industry. In 2015, it even voted to approve a $53 million loan to fund the construction of a controversial coal export terminal in Oakland, California. In 2014, the CIB gave the fledgling infrastructure coalition $55 million to advance the railway.

Meanwhile, the Utah Department of Transportation commissioned a feasibility study, considering more than two dozen different potential railway routes. As with previous studies, the last completed in 2001, virtually all the routes out of the basin were jettisoned as environmentally disastrous, too expensive, or because they threatened ancient petroglyphs or other archeologically significant areas. Elected officials in eastern Utah eventually concluded that the railway construction would cost more than $5 billion, far too much to make it financially viable, especially at a time when oil prices were suddenly crashing. They scrapped the idea.

Yet dreams for a railway still refused to die. One reason might be that it was a full-employment program for consultants whose well-connected firms have collected millions in fees doing one study after another on the same project. One firm in particular, Jones and DeMille, has actually employed Utah elected officials while they were in office, including the former Utah Senate majority leader Ralph Okerlund, a dairy farmer who also served as the first executive director of the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition. But the election of Donald Trump also seemed to reanimate the zombie train as supporters saw an ally in the oil-friendly White House.

In 2019, after commissioning yet another feasibility study that this time claimed the railway could be built for a mere $2 billion, the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition announced that it had formed a public-private partnership to turn the dream into reality. Running the railroad would be the Rio Grande Pacific Corp., a Texas-based privately held freight railroad company. The coalition also partnered with the DHIP Group, an investment firm charged with finding billions in private funding for the railway. The coalition applied for permits from the Surface Transportation Board and pushed for an expedited decision. “By providing an economic alternative to trucking,” it wrote in the petition, “the proposed Project would allow Uinta Basin producers to access new markets, thereby enhancing the quality of life for the residents of the Uinta Basin and its communities.”

The Uinta Basin railway route approved by the STB closely follows Highway 191, which runs parallel to Willow Creek and crosses the rugged Wasatch Mountains through Indian Canyon in a stunningly beautiful part of the Ashley National Forest. When I drove out that way in October, the engineering challenges the mountain posed for a railway quickly became so apparent I wondered whether any of the Salt Lake politicians supporting it had ever actually been there.

My rented Nissan Sentra chugged towards Indian Creek Pass, elevation 9,100 feet, along a narrow two-lane road that hugged the sheer cliff. At the summit, layers of sandstone and limestone had been sliced open to make way for the road. Wire mesh had been installed to shore up the crumbling rock walls but during public hearings on the railway proposal, a Utah highway patrolman who owns a ranch along the railway route testified that landslides were a chronic problem on the road. “We have boulders rolling off that mountain constantly,” he said. “They are half the size of the cars. They roll right across the road…I just can’t imagine a train going through and vibrating those things through all the time.”

Indian Creek Pass is far too steep for a train to go over. Instead, the railway will blast through the mountain in five tunnels, one at least three miles long. But going through the mountain may be just as treacherous as going over it. Inside the unstable mountain rock are pockets of explosive methane and other gasses, not all of which have been mapped. Noting that such hazards “could potentially cause injury or death,” the STB suggested in its environmental review that before blowing up the mountain, the coalition should perhaps conduct some geoengineering studies, which it hadn’t done.

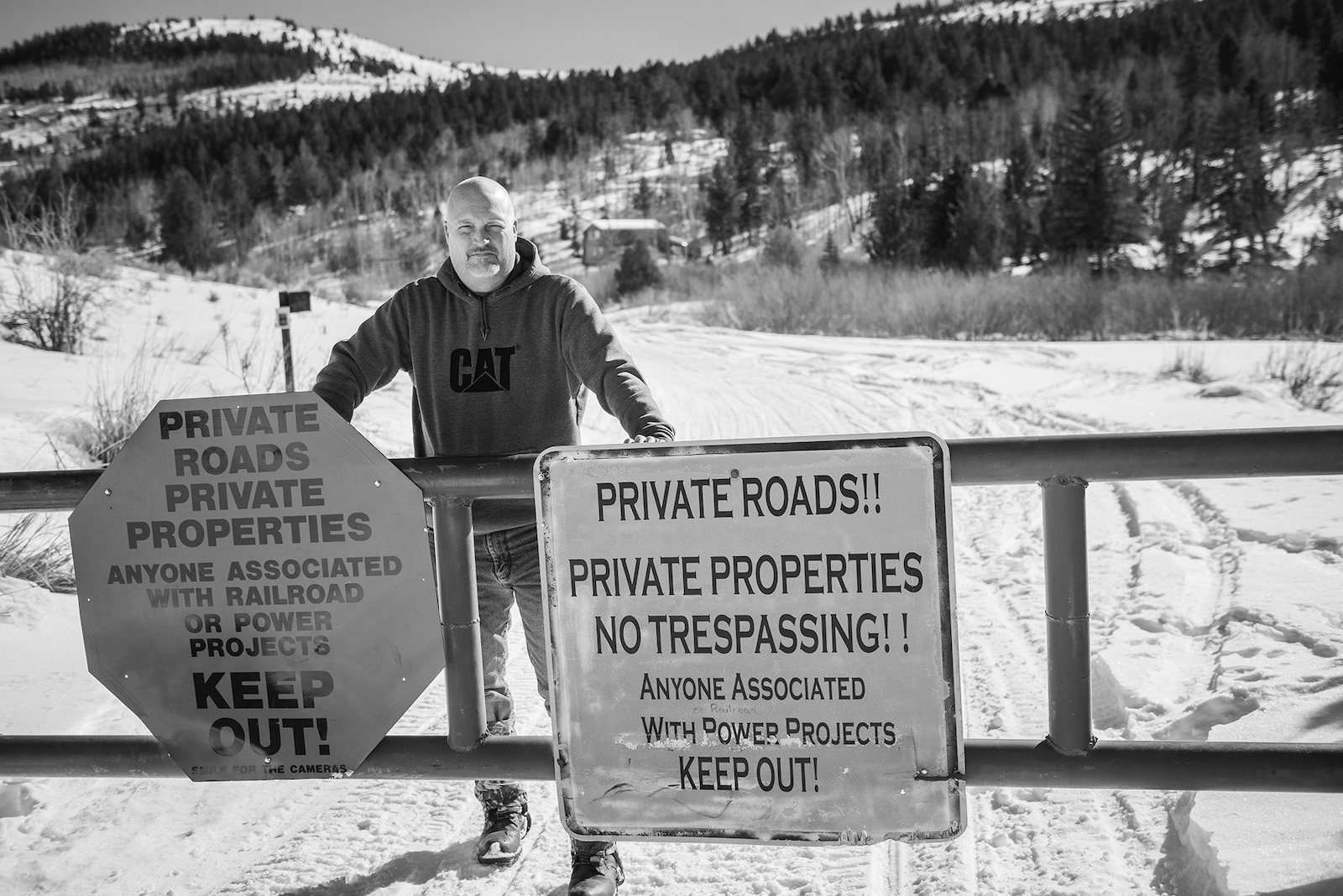

The railway’s largest tunnel will come out about a half-mile from the end of Darrell Fordham’s property in Argyle Canyon, a secluded mountain community near Indian Creek Pass of about 400 modest cabins. With no water or sewer lines and no electricity, the community is a place where people put up security cameras not to catch burglars but to watch the bears and other wildlife. “We’ve got these beautiful properties up there that are completely off-grid that are peaceful,” he told me ruefully, “and they’re going to destroy it.”

A business owner who lives most of the year in Lehi, Fordham has raised serious questions about the viability and environmental impacts of the project at public meetings, even pursuing legal action. “But you know, it just feels like anything that we as landowners have expressed has largely just fallen on deaf ears,” Fordham said. “Even our state representatives — the governor and senators — they all look at the project and just buy into the ‘Oh it’s going to create jobs and stimulate jobs in that area. It’s got to be a good thing.’ They just refuse to look at the reality of it.”

Railway construction may indeed create a lot of jobs, at least for a while. Various estimates put the number of workers needed for the massive construction project as high as 3,000. The 2015 feasibility study noted, “This size of the workforce would overwhelm the existing city infrastructure of the local small communities, requiring separate camps with upgraded infrastructure to be built to house the workers.”

When I spoke with Fordham in January, there were five feet of snow on his property, another factor that is almost never mentioned in the coalition’s plans for the railway, which call for construction to begin in January 2023. The coalition claims the entire railway can be completed in just two years, despite a 2015 state study estimating that such a project would take more than a decade to complete.

Fordham suspects that the coalition also is vastly underestimating the railway construction costs, and the ability of the private sector to pay. Indeed, its own consultants concluded in 2018 that the project would require government bonds because “any railroad which may eventually service the line has relatively little incentive to invest in the construction of the line, especially given the high associated capital costs.”

He worries that if construction is allowed to begin, any private money will quickly run out and the state and federal governments will get stuck paying to clean up the mess or complete the project. “When they go blast through an entire mountain like that, there are no mitigation measures, no monitoring to see what those impacts are going to be,” Fordham says. “They just grant them carte blanche to destroy whatever they want in the watershed.”

To make the Uinta Basin railway profitable, oil companies need to commit to consistently shipping at least 130,000 barrels of oil a day on it, nearly twice the basin’s current production level. But the industry is notoriously vulnerable to boom-and-bust cycles, and during the past few years, oil companies have lost a huge amount of money even when they were producing a lot of oil. Throw in the rapid development of electric cars and a worldwide move away from fossil fuels and the industry’s future is anything but certain. “From a financial point of view, the inherent volatility of oil prices can make it harder to justify big, long-term infrastructure investments” like the railway, says Clark Williams-Derry, an energy finance analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a nonprofit think tank focused on sustainable energy.

Indeed, one of the major oil producers in the Uinta Basin, EP Energy, was just emerging from bankruptcy when its chief operating officer, Chad England, sent a letter to the STB supporting construction of the railway last year. In March, the company agreed to pay a $700,000 fine and spend more than one million installing pollution controls on its existing wells to settle an EPA complaint about violations of the Clean Air Act in the basin. EP Energy creditors had been trying to sell the company to another large oil company in the basin, but the Federal Trade Commission blocked the merger on anti-trust grounds. In late March, the FTC approved the sale but required the new company to divest all its Utah assets to protect competition and lower gas prices. Given all that, the company seems like an unlikely candidate to commit to a multi-million-dollar railway shipping contract.

“If there were money to be made, someone would have built this railroad 20 years ago,” says Justin Mikulka, a research fellow at New Consensus, a think tank where he studies the finances of energy transition. “If this were a financially viable project, why didn’t Exxon or someone do it?” he asks. “To me, the economics are never going to work on this.”

Which leads to the obvious question: How does such a dubious and potentially disastrous fossil fuel project get so far along in the process, with support from both Republican and Democratic presidential administrations, at a time when the dangers of climate change are so pressing?

The obvious answer? Politics, of course.

Let’s start with the low-level officials in the Uinta Basin itself. Ronald Winterton was a Duchesne County commissioner who served on the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition board from 2015 through early 2019. He also served on the Permanent Community Impact Board, which in 2018, voted to suspend its own rules to rush through the first $6 million of a $27 million grant to the coalition to get the project approved before Trump left office. According to minutes from the meeting, Winterton said, “Let’s get this going. Because the longer we wait…we could change administrations and then we’re going to have problems.”

At the time, Winterton was employed as a consultant by Jones and DeMille Engineering, which has done millions of dollars of work on the railway, paid for with the CIB grant Winterton had voted for. Winterton — now a Utah state senator — did not respond to a request for comment, and a call to Jones and DeMille went unreturned.

Even with these well-placed supporters, the railway would have stalled were it not for the federal Surface Transportation Board, which has to approve additions to the interstate rail network. In January 2021, just before Biden was inaugurated, the three-member board granted preliminary approval for the railway. The board’s lone Democrat, Martin Oberman, a former Chicago alderman who’d served on the board of Chicago’s commuter rail Metra, wrote a scathing dissent. He questioned whether the “environmental impact of the project will outweigh the project’s transportation merits,” which he called “at best uncertain.” Oberman argued that the board had not scrutinized the financial viability of the railway, even though the coalition’s consultants were quite clear in a 2018 feasibility study that “the private sector will not build this railroad,” he wrote. “Only a government can afford to build it.”

Oberman singled out the coalition’s financing partner for its lack of railway construction experience. On its website, DHIP lists only three projects that it has worked on to date, and one is the Uinta Basin Railway. Another involved a controversial oil export terminal in Louisiana’s Plaquemines Parish that was canceled in November last year (though you wouldn’t know that from the DHIP website). No one from DHIP responded to several requests for comment.

After his inauguration, Biden appointed Oberman STB chairman, and then in April 2021, he tapped one of Oberman’s Chicago colleagues, Karen Hedlund, to replace one of the departing board members who’d voted in favor of the Uinta railway. But Senator Mike Lee put a hold on her nomination, which then stalled for the rest of the year. On December 15, 2021, the STB issued its final decision approving the railway. The very next day, the Senate confirmed Hedlund. Lee’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

As I started the steep descent from Indian Creek Pass towards the town of Duchesne, Highway 191 wound around an array of eerie sandstone formations and past a sign that read “Ashley National Forest, land of many uses.” A few yards beyond the sign, a pumpjack rocked quietly up and down. In late October, the Forest Service tentatively approved a right of way for the oil trains to pass through this forest. In a letter to environmentalists, Forest Service chief Randy Moore claimed that the decision supported Biden’s executive order on climate change and would “rebuild our infrastructure for a sustainable economy…as products move quicker and safer by railway than by tractor-trailers on a highway.”

Moore argued that the decision didn’t violate regulations prohibiting new roads on protected roadless areas because “a railway does not constitute a road.” He said the railway construction would not impact the roadless area. How train tracks would materialize in the middle of a roadless wilderness area was unclear. The Forest Service did not respond to a request for comment.

One day while driving around the Uinta Basin in October, I learned from KLCY, the local country music station, that a group of attendees of a National Association of Counties regional meeting in Salt Lake was being feted by local dignitaries in Duchesne County, a member of the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition. They had taken a three-hour bus trip from Salt Lake to “learn about the county’s economy and natural resources, including the petroleum extraction industry,” read the event description. “The tour will continue to a nearby petroleum site to observe the production process and learn how industry complies with regulations.”

Among the conference’s featured speakers was Utah Department of Natural Resources Director Brian Steed, who had served as the acting director of the Trump BLM. Also appearing was American Stewards of Liberty executive director Margaret Byfield, representing her sagebrush-rebellion style group dedicated to fighting the Biden administration’s conservation initiatives.

But the most prominent speaker was Biden’s Forest Service chief Randy Moore. While in Salt Lake, he met with the Uinta Basin railway promoters and expressed support for the project. “In my opinion, we have somebody on our side back there in Washington,” Uintah County commissioner Bart Haslem reported back to a meeting of the Seven County Infrastructure Coalition a week later. “[Moore] felt like it’s a viable project. I think we have somebody there who will help us push that through.” Four days later, the Forest Service issued preliminary approval of the right of way for the railway. The White House and Biden’s “climate czar” Gina McCarthy never responded to my many emails asking how the Forest Service decision comported with the president’s climate change executive order.

Meanwhile, Senator Mike Lee recently complained in a basin radio interview that the Forest Service isn’t moving fast enough to finalize the permitting for the railway. But the agency is now getting pressure from outside of Utah as the broader impacts of the infrastructure project are becoming more apparent — especially in Colorado. Oil trains from the Uinta Basin will most likely head south to link up to a rail line that parallels I-70 directly along the Colorado River. Eagle County, Colorado, has sued the STB arguing that it failed to take into consideration the environmental impacts on downstream users, particularly the risks of wildfires, when it licensed the rail line. The suit is supported by both of the state’s Democratic senators.

Russel Albert Daniels for Mother Jones

Concerns spread beyond Western states. At the end of March, environmental justice groups on Louisiana’s Gulf Coast wrote to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, who oversees the Forest Service, protesting that the agency had failed to consider that 85 percent of the oil shipped on the Uinta Basin railway would end up at Gulf Coast refineries, many of which are already polluting historic Black neighborhoods where residents suffer from a wide range of health problems. “Our communities have suffered for years from the environmental injustice inflicted by the fossil fuel industry,” they wrote. “The massive influx of oil via train from Utah will only make our situation worse.”

I followed the railway’s proposed path through the Ashley National Forest and the road leveled out into an unnaturally green valley, where ranchers irrigate alfalfa in close proximity to more oil wells. Highway 191 eventually emerged near the Duchesne city cemetery where it becomes Route 40, and the scenery transforms into what environmentalists have dubbed “Mordor,” the heart of the basin’s oil and gas industry that, like J.R.R. Tolkien’s fictional hellscape, is also surrounded by mountains on three sides.

Even without the railway, oil and gas development in the basin already creates some of the highest ozone levels in the world. The mountains surrounding the Tavaputs plateau trap pollution in a thick layer of smog in the winter that regularly violates the Clean Air Act even though few people live out here. Among those who suffer from the poor air quality are about 1,500 members of the Ute tribe who live on the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation, which at 4.5 million acres is the second-largest reservation in the country.

While indigenous people have been instrumental in fighting oil pipelines elsewhere, the Utes have long been active in oil and gas development, and they have wells on the reservation. The tribe is now an equity partner in the Uinta railway, and it has agreed to let it pass through tribal lands even though it threatens several endangered plants that Utes consider sacred. No one from the tribe responded to several requests for an interview.

Unable to interview any tribal leaders, I took a short detour from Route 40 to do a little rubbernecking on a pocket of private land inside the reservation now called Skinwalker Ranch near the end of the railway route. The ranch is Utah’s version of Nevada’s Area 51. For a century, people have reported witnessing unusual phenomena here — everything from cattle mutilation to alien abductions. The Pentagon has funded UFO research at the ranch, and there’s even a UFO-themed campground nearby.

A few years ago, a Salt Lake real estate developer named Brandon Fugel bought Skinwalker Ranch and continued the previous owners’ UFO research. He now stars in the History Channel series “The Secret of Skinwalker Ranch.” On the show, he jumps into his Maserati looking like a Bond villain and races through Salt Lake to an awaiting helicopter that whisks him away to the ranch. I wondered how Fugel felt about the prospect of having two-mile long oil trains rumbling near his ranch all day, every day, given what all that vibrating might do to UFO research — or the prospects of a fourth season of his show.

Unfortunately, he didn’t respond to my requests for comment, and the History Channel turned down my request for a tour. It turns out that the ranch superintendent is the son of Utah state Senator Ronald Winterton, one of the railway’s biggest promoters. But I did manage to talk to Ryan Skinner, who has written a number of books about the ranch. He knows Fugel and other paranormal investigators in the basin. One of them, Space Wolf Research, actually has an office close to where the railway will start in Myton. The driver of a semi, Skinner lives in Wisconsin but he makes a trip to the Uinta Basin monthly to scan the dark skies and continue his investigation into the mysteries of the mesa, after having his first close encounter 15 years ago.

He says that UFO researchers have only just figured out how to keep the fracking booms from screwing up their measurements and couldn’t imagine the impact of the railway on their work. Skinner says he has nothing against oil development and has long heard about the plans for the railway. Somehow, he didn’t think it would ever happen. “Taking these hidden gem locations and really industrializing it to such a degree, it really bothers me,” Skinner explains. “This is like holy land out there. This just feels like land that needs to be left alone.”

Skinner may view the Uinta Basin as sacred ground, but many of the people who live there see it as barren land ripe for exploitation that should not be impeded by federal regulations or pesky environmentalists from the city. “Leave us the hell alone,” Vernal insurance agent Mark Winterton said angrily at a 2020 hearing on the railway. “Where we’re running this railroad, it’s land that mostly is basically wasteland. Nobody is there…If you don’t live out here, I don’t feel like you should even have a say.”

I understand what he means about the wasteland. When I tried to drive the last leg of the railway route to its eastern terminus near the town of Myton, I discovered that the only main thoroughfare is unpaved. Crossing it in a Sentra proved to be a really bad idea. A wide open, desolate stretch of land crisscrossed with dirt roads named for well numbers, the Leland Bench area is where railway promoters are planning to construct a rail trans-loading facility as well as a new oil refinery. As I searched fruitlessly for a cell signal near Chevron Pipeline Road, it was easy to see how people like Winterton would consider this land expendable.

Even so, this scrubby plateau is surrounded by public land that belongs to everyone, even us city slickers. It’s about 50 miles from the Dinosaur National Monument Quarry visitor center, a marvel of archeology and the western edge of a “Dark Sky” national park that is one of Utah’s underappreciated natural gems. Less than 20 miles to the east, at the Ouray National Wildlife Refuge, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is trying desperately to save endangered native fish in the Green River. And yet, the Biden administration is preparing to greenlight a railway that would only hasten their demise. “Utah is kind of the epicenter” of these sorts of local fights about climate change, says the Center for Biological Diversity’s Deeda Seed, which means the proposed railway “affects the fate of not only our state but other states.” In the end, she concludes, “All of these decisions matter now.”