The United States is rejoining the Paris climate agreement, fulfilling one of President Joe Biden’s earliest campaign promises and generating sighs of relief around the world as governments struggle to keep the planet’s temperature from surging to even more dangerous levels.

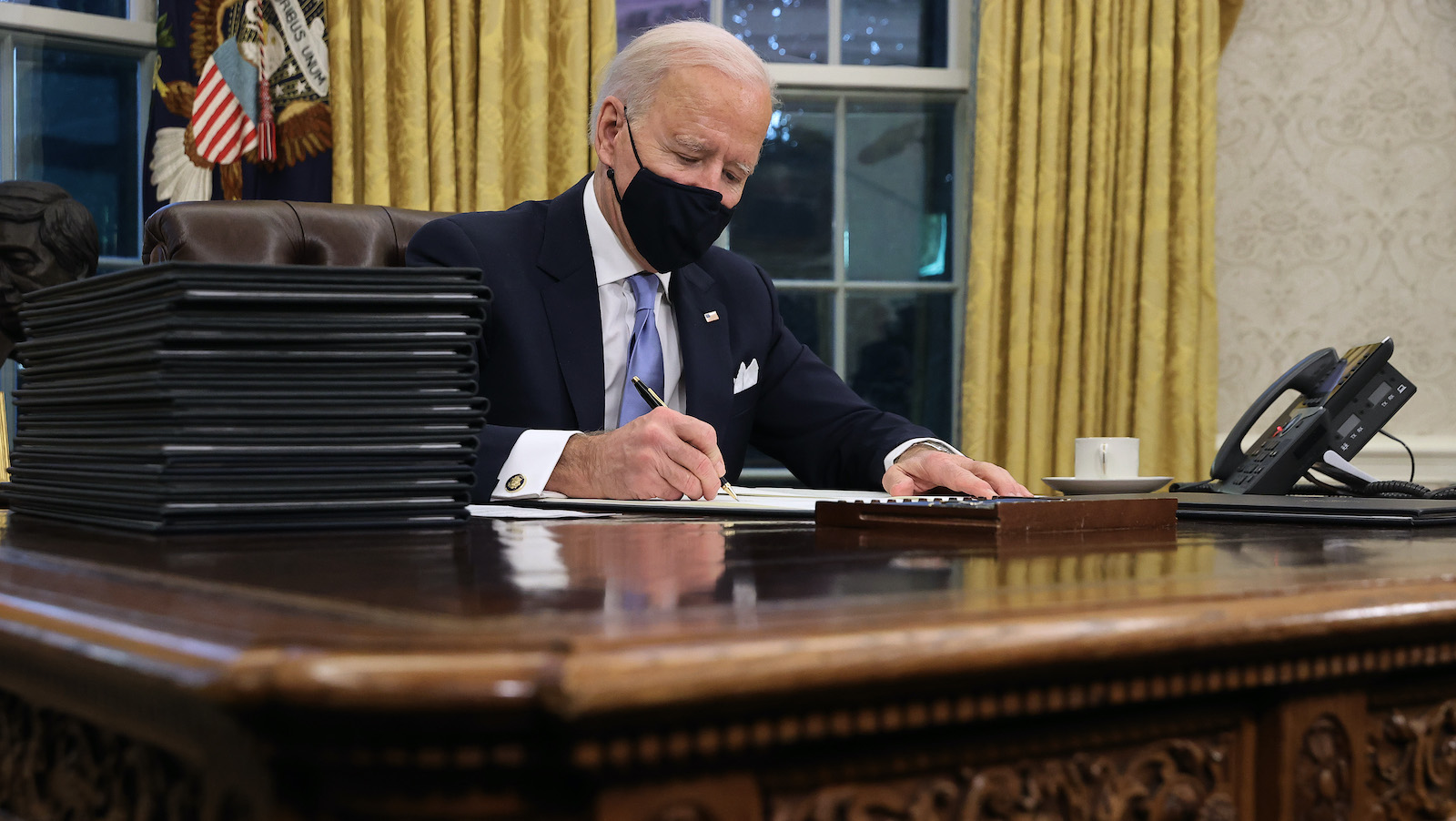

On Wednesday, just five hours after his inauguration and amid a flurry of other presidential actions, President Joe Biden signed an executive order returning the U.S. to the landmark accord to slash carbon emissions. The move will be official in 30 days.

It’s been three and a half years since President Donald Trump first announced plans to pull the U.S. out of the Paris deal, and in some ways the rest of the world has moved on. Despite fears that it would set off a mass exodus, no other countries have exited the agreement, and many have even ratcheted up their carbon-cutting targets. China, once seen as the biggest obstacle to climate progress, has vowed to zero out its emissions by 2060; the United Kingdom, European Union, Japan, and Korea are aiming to cut emissions to zero even earlier, by 2050.

But without the U.S. on board, the central goal of the agreement — to prevent dangerous levels of global warming — would be virtually impossible. The planet has already warmed by 1.2 degrees Celsius since the late 19th century, and the U.S. is responsible for around 15 percent of the world’s carbon emissions, making it the second-largest polluter after China.

“President Biden has given America and the world a clear sign that his administration views climate change as an existential crisis,” said Fred Krupp, the president of the Environmental Defense Fund, in a statement.

Rejoining the agreement, however, is just the first step. To fulfill its obligations under the pact, the Biden administration will have to quickly throw together a plan to cut greenhouse gas emissions before the next U.N. climate meeting, scheduled for December in Glasgow. Other countries will expect the U.S. to come with a goal to slash CO2 emissions by 45 to 50 percent by 2030 (compared to 2005 levels) and get overall emissions to zero by the middle of the century. And it won’t be enough for the United States just to set those targets. Biden will also have to show the country can reach them — and that it can be counted on not to back out for a second time.

“Even though the world is excited to welcome them back, it leaves a scar,” said Rachel Kyte, a former special representative for the United Nations and dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University. “In the back of people’s minds, it’s: ‘They walked away once. Could they walk away again?’”

The agreement, after all, was designed with a possible U.S. exit in mind. Diplomats, worried about a climate-denying stage in American politics, built in a four-year holding period for any country trying to leave the accord. That’s why, even though Trump said he would exit back in 2017, the U.S. couldn’t officially leave until this past November.

Still, the 189 countries that stayed in the agreement aren’t doing a great job at cutting their emissions either. According to the independent analysis group Climate Action Tracker, virtually every country in the world is off track when it comes to meeting the stated goals of the Paris Agreement. And even if countries do fulfill their current pledges, the planet is still on track to warm by about 3 degrees Celsius.

Kyte says that the U.S. rejoining could help address those gaps in global ambition. Over the past four years, the country’s absence “gave other countries permission not to be their best selves,” she said. Countries like Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Brazil were able to hide behind the U.S.’s failure and avoid scrutiny of their rising CO2 emissions. Now, with Biden stepping back into the action, “it takes the space away for these countries to skulk around the edges.”

Some of this has already begun. In Australia, experts are already worried that the government of Prime Minister Scott Morrison will be “isolated” if it continues to drag its feet on climate action. The incoming Biden administration has also promised to “name and shame” countries that don’t comply with global targets, calling them “climate outlaws.”

But for the U.S. to really apply pressure internationally, Biden is going to have to start passing some climate legislation at home. And, with the slimmest-possible majority in the Senate, the Biden administration faces a tough road ahead.