In mid-September, beneath a smoky gray sky, California Governor Gavin Newsom stood at a podium in Sequoia National Park. Directly behind him, an entrance sign wrapped in fire-resistant foil resembled a chrome holy cross. After another summer of dangerous heat waves, wildfires, and drought, he was there to offer salvation for the scorched Golden State in the form of a $15 billion climate package.

“California is doubling down on our nation-leading policies to confront the climate crisis head-on,” he announced. But among the 24 climate change-related bills the governor signed into law that day, none would fill a notable gap in California’s climate strategy — a long-term plan to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

In the past few years, many states have passed new laws requiring that they achieve “net-zero” emissions by mid-century. Virginia, New York, Washington, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island all plan to cut emissions across their economies by 80 to 90 percent by 2050, and to offset any remaining emissions using either nature-based solutions known as carbon sinks, like trees and soils, or technology to suck carbon out of the air. Several more states, including Oregon, Colorado, and Minnesota, have legally binding targets to reduce their emissions by at least 75 percent by 2050.

Many of these laws were passed in response to a landmark report released by an international group of scientists in 2018. The report found that the whole world needed to cut carbon emissions in half by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 in order to fulfill the Paris Agreement’s promise of trying to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. The planet will not stop heating up until net-zero emissions is achieved.

But although California passed some of the first and strongest laws to tackle climate change in the nation, its legally mandated economy-wide emissions goals stop at 2030.

“We like to talk about how we’re leading the nation in the fight against climate change,” State Assembly Member Al Muratsuchi told Grist. “But increasingly we’re falling behind.”

This past legislative session, Muratsuchi introduced A.B. 1395, a bill that would have brought the state up to speed by enshrining in law a goal to achieve net-zero by 2045. Muratsuchi and his coauthor, Assembly Member Cristina Garcia, worked hard to appeal to diverse constituents by including provisions they thought would serve fossil fuel workers and frontline communities alike. But the bill failed to pass muster with either group and ultimately died on the Senate floor.

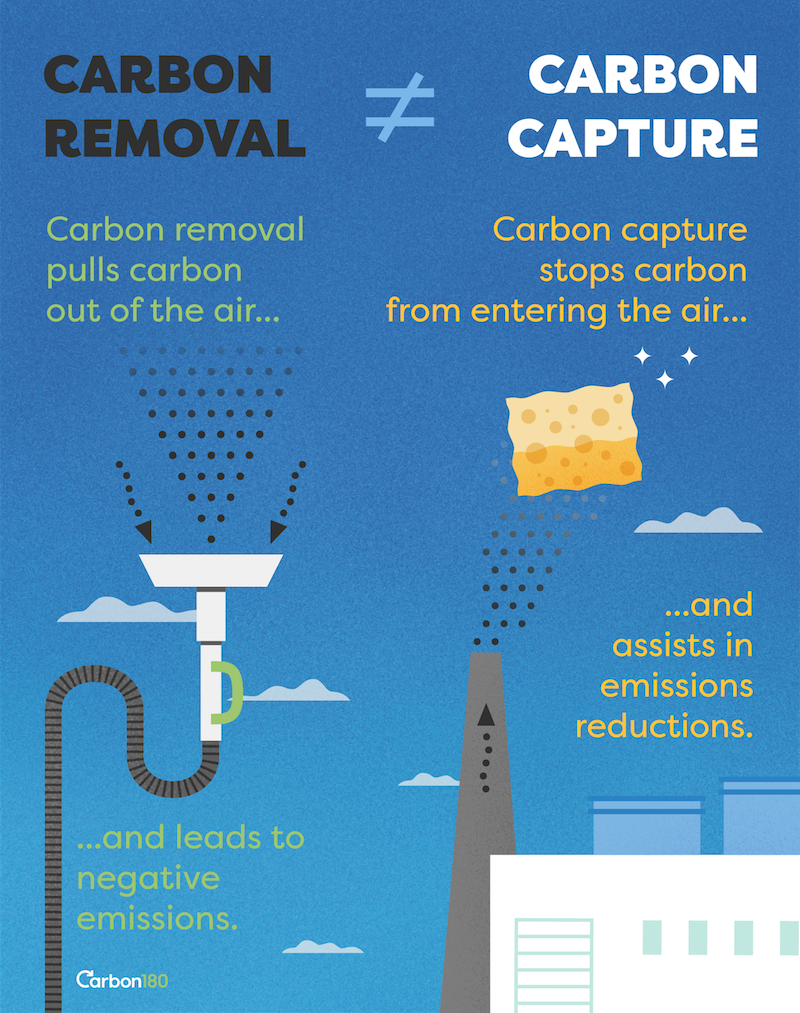

The story behind A.B. 1395 highlights one of the biggest areas of tension in the politics of climate change around the world right now: disagreement over the need for carbon capture and carbon removal.

Carbon capture systems can be installed in the smokestacks of power plants and industrial facilities to trap carbon dioxide before it reaches the atmosphere. Carbon removal refers to solutions that siphon carbon dioxide that has already been emitted out of the air, whether by planting trees, or building giant fans that literally suck carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, known as direct air capture machines.

That landmark 2018 report, and many studies since, have concluded that both carbon capture and carbon removal will be needed to stabilize the climate. But a large contingent of the climate and environmental movement, including researchers, justice advocates, and policy experts, reject these solutions due to concerns about locking in dependence on fossil fuels, further burdening communities with pollution, and wasting time and resources on plans that may never pay off.

As seen in California, the debate threatens to slow climate action at a time when it’s becoming increasingly urgent.

Currently, California has two key laws driving down its emissions. One requires that 60 percent of all electricity in the state come from renewable sources by 2030, and that by 2050, 100 percent of the state’s electricity be carbon-free. The second law applies across the economy — including transportation, industry, and agriculture — and says California must cut total emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030.

In 2018, then-Governor Jerry Brown issued an executive order setting a goal of net-zero emissions by 2045, but until the legislature puts it into law, it is little more than an aspiration. Muratsuchi’s bill would have changed that, but more importantly, it would have put in place rules defining what “net-zero” means in California. The phrase has no single definition and merely implies a balance between sending carbon into the atmosphere and removing it by sucking it back down to Earth. In theory, viable paths for net-zero could involve moving toward an almost entirely renewable energy system — or continuing to dig up and burn fossil fuels while building a vast web of infrastructure to vacuum up the related carbon emissions from smokestacks and from the atmosphere.

Muratsuchi’s legislation narrowed the possibilities in two ways. First, it would have required that California cut its emissions by 90 percent, allowing only 10 percent of the state’s remaining greenhouse gases to be offset with carbon removal. Second, it would have put guardrails on the use of both carbon capture and carbon removal.

There are no carbon capture systems or direct air capture machines operating in California today, and there’s a lot of uncertainty about the extent to which they can be economically deployed. But a report on carbon neutrality commissioned by the state found that even if California totally phases out fossil fuels by 2045, carbon capture could still be necessary to cut emissions from industrial facilities that emit carbon dioxide, like cement, glass, and chemical plants.

In this version of the future without fossil fuels and with some carbon capture, the state would still emit greenhouse gases — the equivalent of 33 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year — from refrigerators and air conditioners, agriculture, and landfills. While some of those emissions could be balanced out by enhancing natural carbon sinks like forests, the potential for natural carbon removal is limited. One study estimated that California’s lands could sequester up to about 17 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year while another estimated that the state’s nature-based carbon sinks could capture up to 25 million metric tons per year. Direct air capture machines are one possible way to make up the difference.

It’s clear that it would be very difficult for California to achieve net-zero without some carbon removal. But most technological carbon removal methods, including direct air capture, are in their infancy, and it’s unclear how much they can be sustainably or economically deployed. Doubts over whether carbon removal solutions will be able to scale up are why A.B. 1395 capped reliance on carbon removal to just 10 percent of emissions.

It did not put any such cap on the use of carbon capture systems to lower emissions, nor did it dictate which types of facilities could install them, or legislate a plan to phase out fossil fuels — features that should have appealed to the fossil fuel industry and its union workers. However, A.B. 1395 did direct a state regulatory agency called the California Air Resources Board, or CARB, to come up with criteria for the use of these systems and rules to ensure they would not have harmful effects on local air quality or public health.

That’s because carbon capture doesn’t necessarily clean up other kinds of smokestack pollution that are more directly harmful to human health than carbon dioxide. The process also requires a lot of energy, and if the energy comes from natural gas, it has the potential to increase local pollution of nitrogen oxides and fine particles.

The bill contained one more constraint: Today, captured carbon dioxide is often sold to oil companies and pumped into old wells to coax more oil out of the ground. The bill would have prevented this from counting as a way to reduce emissions — requiring carbon capture operators instead to just bury the carbon underground for permanent storage. It put similar guardrails on direct air capture systems.

“We wanted to make sure that these were real and verifiable reductions of greenhouse gas emissions and not just excuses to continue to burn and pollute using fossil fuels,” Muratsuchi told Grist.

If you’re not very familiar with California politics, it may come as a surprise that this liberal, Democratically-controlled state failed to pass the kind of long-term climate target that more conservative states like Virginia or Colorado have now successfully passed. But unlike many of the other states with net-zero laws in place, the fossil fuel industry is a major part of California’s economy. It is one of the top 10 oil-producing states in the U.S. and the third-largest refiner of crude oil.

Even though A.B. 1395 left the door open for some continued fossil fuel use by allowing for carbon capture, the state’s building trades unions, which represent fossil fuel workers, came out in full force to fight it. They sent newsletters to members telling them not to support the bill and called in to oppose it during legislative hearings, arguing that cutting emissions by 90 percent would put millions of jobs at risk.

The building trade unions and the Western States Petroleum Association, which represents oil and gas companies in the West, have formed an official alliance called Common Ground. Muratsuchi said the alliance has consistently killed the legislature’s most ambitious climate bills, pointing to another piece of legislation that died earlier this year that would have banned fracking and required more distance between oil wells and homes. “The oil industry doesn’t want any limits on their business, and the State Building and Construction Trades don’t want any limits on their jobs,” said Muratsuchi.

In addition to citing job losses, fossil fuel workers and industry lobbyists said that A.B. 1395 would stifle innovation in the state — presumably by seeking to regulate the use of carbon capture. (The California Building Trades Council, the Western States Petroleum Association, and several other trade associations and unions that testified against the bill did not respond to Grist’s requests for an interview for this story.) During a hearing on the bill, Timothy Jefferies, the business manager for Boilermakers Local 549, said it would hurt “innovation, technology, and manufacturing designed to meet the climate crisis.” Jefferies warned that California’s burgeoning electric vehicle manufacturing industry could pick up and move to a different state “where manufacturing is offset by carbon capture.”

Many California Democrats are beholden to labor, according to R.L. Miller, a Democratic National Committee member who chaired the state party’s environmental caucus for eight years. She said the building trades unions provide a lot of the muscle to get Democrats elected in the state. They volunteer for campaigns, knock on doors. “You’re lucky if you can get like five climate people to show up,” she said.

But Miller and Muratsuchi both acknowledged another shortcoming that is killing ambitious climate plans in California: The state has not yet made a credible case that climate action will be a win-win for labor — that a “just transition” for workers is possible or likely. “We need to show them what a just transition looks like with real jobs, not just rhetoric,” Miller said, assigning some blame to the renewable energy industry for being hostile to unions. “I think so far, the reality has not yet caught up to the rhetoric that we are using. Which is not to say it’s never going to happen.”

A.B. 1395 never stood a chance without support from labor unions. But the bill also failed to win the approval of several prominent California environmental justice organizations that either opposed the bill or remained neutral. Their rejection of the compromise measures around carbon capture and carbon removal illustrates the challenges of finding a path to carbon neutrality that frontline communities can get behind.

Martha Dina Argüello, the executive director of Physicians for Social Responsibility-Los Angeles, told Grist that carbon capture will increase local pollution and said she had no confidence in the guardrails that Muratsuchi and Garcia had put on their emissions-reductions plan. “We’re very nervous about the linkage of those reductions to a technology we don’t think works and actually continues to push burdens onto low-income communities,” she said.

In August, her organization, along with 13 other California-based environmental justice groups, sent a letter to CARB asking it to reject the use of carbon capture and direct air capture in the state’s climate plans altogether. The letter urged the agency to establish a stronger public health framework. “As we think about these big broad goals,” she said, referring to the 2045 net-zero target, “we have to have big broad goals about making the air cleaner where we breathe. Just focusing on carbon doesn’t do that.”

Roger Lin, climate and air counsel for the California Environmental Justice Alliance, echoed Argüello’s argument. He also worries that giving carbon capture the green light as A.B. 1395 did will begin to funnel state resources away from other solutions. “It brings up a bigger issue of, where are the state dollars for innovation going to be invested? Are they going to be invested to perpetuate the existing energy economy that we have with the oil industry, or are we going to invest the innovation dollars into renewables and long-term storage?” he asked, referring to the need to develop batteries that can store energy for the power grid for long periods of time when the sun isn’t shining and the wind dies down.

When asked about the argument that carbon capture might be needed to cut emissions from California’s cement plants, for instance, Lin acknowledged that it’s a tough area to solve. But he wondered whether some of the billions of dollars the Biden administration is pouring into carbon capture research and development could instead be put toward finding alternative ways to cut emissions from cement production.

Argüello questioned whether achieving net-zero emissions was even the best goal for California, considering that there did not seem to be a way to meet it without banking on risky solutions that sacrifice justice and equity. “If we set these targets for which we don’t really have the measures to meet, then we end up using accounting tricks, such as offsets,” she said. “If you want to set goals, then start from ‘we want to end fossil fuel production,’ and work backwards.”

The conflicts that plagued A.B. 1395 are not unique to California. National environmental justice groups criticized the Biden administration’s infrastructure law for funding what they consider to be “false solutions” to climate change like carbon capture and direct air capture demonstration plants. During COP26, the United Nations climate conference in Glasgow, swarms of activists marched the streets with signs that said “Net-zero is not zero,” arguing that the goal of net-zero by mid-century allows governments and companies to delay action on climate or obfuscate their plans to cut emissions.

Dave Weiskopf, the senior advisor for climate at NextGen Policy, a progressive policy nonprofit, said this is exactly what A.B. 1395 was designed to prevent. Right now, the California Air Resources Board is in the middle of updating its scoping plan, a roadmap that lays out how the state will achieve its emissions goals. Without the explicit instruction to cut emissions by 90 percent, the agency could put forward a plan that relies heavily on carbon removal to cancel out emissions that it deems either too technically challenging, expensive, or politically difficult to cut. “It’s really hard to cut emissions as much and as fast as we’re trying to do, and there’s a lot of pressure to try to find ways out of some of the biggest jams,” said Weiskopf. To him, there’s no reason to believe sucking lots of carbon out of the air will be easier or cheaper.

Another way to prevent net-zero plans from passing the buck is to do what California has already done — set a near-term target. The 2018 report on limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C that kickstarted the net-zero mania assumes that emissions are consistently declining over time starting today. Long-term plans to get to net-zero will not avert catastrophic climate change if carbon reductions don’t start now. Since carbon sits in the atmosphere for hundreds of years, every ton that goes in today helps to determine how bad things will get. “It feels like the whole cumulative element of this is still missing from the policymaker conversation,” said Pam Kiely, the associate vice president of U.S. climate at the Environmental Defense Fund.

To Kiely, California’s sluggishness in setting a net-zero target does not mean that the state has fallen behind or lost its title of climate leader. “California is at a level of sophistication that dwarfs where the conversation is in other states,” she said, explaining that it’s one of the only places that has a suite of regulations in place designed to cut emissions in the near term. “That is leaps and bounds ahead of a lot of other places in the country.”

Recent reviews of California’s climate progress have warned that it’s not currently on track to hit its 2030 emissions target. One, conducted by the California state auditor, found that transportation emissions have actually been increasing. Another study found that in 2017, the state’s forests may have acted as a source of carbon dioxide emissions rather than as a sink, due to increased wildfires. But even conducting these studies and being able to scrutinize the policies it has tested out so far put California ahead of other states.

Weiskopf said he thinks it’s inevitable that the California legislature will pass a carbon neutrality target. But to him, A.B. 1395 was a missed opportunity to do that with the right protections in place.

Muratsuchi said he plans to reintroduce the net-zero bill in the next legislative session, but he’s not sure what form it will take yet. One change he’s evaluating is taking any mention of carbon capture out of the bill. He’s also looking at other potential policies that could facilitate a just transition for fossil fuel workers, like a carbon tax that would fund job retraining programs.

“We need to figure out how to make it a win-win situation for climate action and for good union jobs,” he said. “We need to figure out how to make the just transition work.”