On Tuesday, the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis released a report that it has been working on since January 2019. With Republicans in control of the Senate and President Trump in the Oval Office, the policy proposals in the report have no chance of getting enough votes to become law, but that’s not really the point. The 538-page plan is a message in a bottle to Democratic voters: Hang tight, the left has a climate plan.

Let’s hit the rewind button and go back to 2018 — a couple hundred eons ago in coronavirus years, which makes it hard to remember the conditions that started the ball rolling on the Select Committee’s report.

On June 26, 2018, a relatively unknown progressive candidate from the Bronx managed to unseat incumbent Democrat Joe Crowley in New York’s 14th congressional district. That progressive, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, campaigned on the Green New Deal, an economy-wide proposal to achieve emissions reductions and economic equity simultaneously.

At the same time, a group of young climate activists and Bernie Sanders stans called the Sunrise Movement — buoyed by progressive wins in the midterms — were ramping up a grassroots campaign in support of that very plan. The Green New Deal, an idea that had existed in relative obscurity for years before the midterms, burst onto the national stage a week after the November election, when the Sunrise Movement set up camp in House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office and Ocasio-Cortez, who was attending her freshman orientation on Capitol Hill on that very day, joined them.

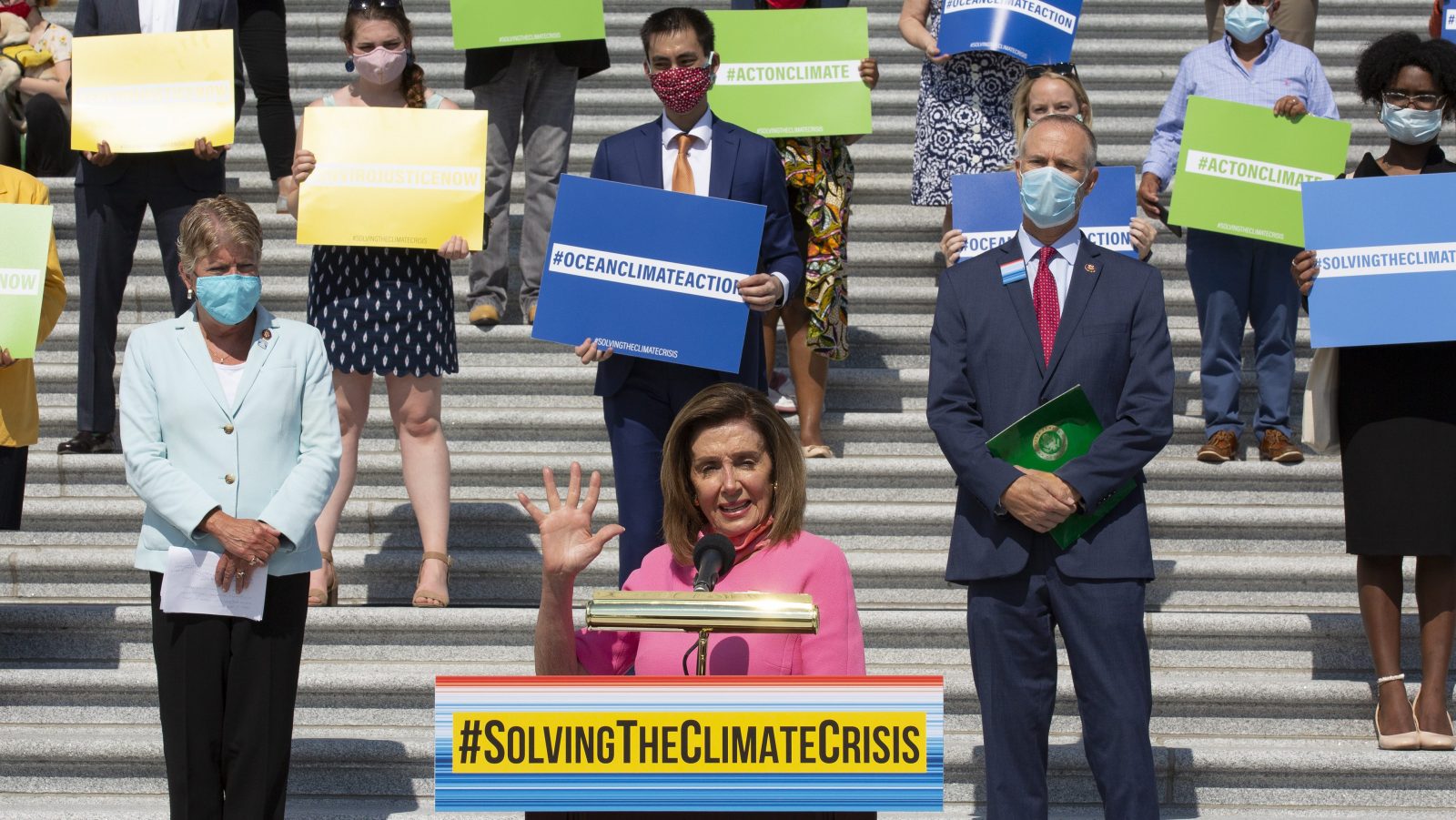

The activists had a list of demands, chief among them a request that the new Speaker of the House create a committee on the climate crisis. Pelosi, a first-wave climate hawk herself, had established a similar panel when she was House Speaker from 2007 to 2011, which was disbanded by Republicans when they regained the majority in 2011. She was quick to do it again, and appointed Kathy Castor, a Florida Democrat and longtime climate advocate, as committee chair. Including Castor, the committee has nine Democrats and six Republicans.

Establishment Democrats would have likely pursued climate policy in the 116th Congress on their own. But added pressure from the progressive wing of their party and a cadre of unyieldingly vocal climate activists, plus some pretty visceral climate change impacts in 2018 and growing concern about rising temperatures among Democratic voters, handed Democrats a mandate to address the crisis.

On Tuesday, the committee unveiled a plan to do just that. The preface notes the inopportune timing of the report, considering the nation is in the midst of both a pandemic and a mass uprising against racial inequity. “Both underscore that there are no foregone conclusions. What we choose to do now shapes the future,” the report says. “What happens next — for racial equality, for public health, for the climate crisis — depends on us.”

The policy targets laid out in the report are a testament to how much the left has moved the Overton window on climate in recent years. The report recommends eliminating emissions from the electricity sector by 2040 and achieving net-zero emissions across the board a decade after that. It suggests that all new vehicles sold in the United States should be electric by the year 2035. It recommends putting a price on carbon and then funneling that money to low- and mid-income households, a emissions reduction tactic that also has some traction on the right.

Most importantly, especially now, the report connects the dots between racial inequity and rising temperatures. Climate change is already impacting low-income communities and people of color. The report includes a long list of policy proposals to alleviate that burden. The list includes allocating funds to decarbonize and retrofit all public housing in the U.S., boosting federal funding for residential solar projects that would help poor communities pay for clean energy, and increasing tax credits and efficiency incentives for developers building affordable housing. Many of the recommendations put forth by the report echo legislation that has already been introduced in Congress. The recommendation to decarbonize public housing, for example, mirrors Ocasio-Cortez and Sanders’ Green New Deal for Public Housing Act, which was introduced in 2019.

The report has garnered praise from climate advocates across the political spectrum. In a statement to Grist, the Sunrise Movement’s legislative manager, Lauren Maunus, said the report is a good start. “We are happy to see the Select Committee’s Action Plan reflect much of the vision for a Green New Deal,” she wrote. “This plan is more ambitious than anything we have seen from Democratic leadership so far, but it still needs to go further to match the full scale of the crisis.”

An effective climate plan hinges on three major pillars, Sam Ricketts, formerly climate director of Washington Governor Jay Inslee’s presidential campaign and now a senior policy adviser for Evergreen Action, an organization that provides policymakers with an open-source climate policy platform, told Grist: Create performance standards for each sector of the economy; funnel federal investments into green jobs; and confront environmental racism by addressing climate impacts in frontline and low-income communities. “These pillars are foundational in this House Select Committee climate crisis report,” Ricketts, who was consulted by the committee on policy items multiple times over the past several months, said. “Ultimately, this is a great foundation upon which Congress can begin to act in a comprehensive and ambitious way to confront this climate challenge.” He noted that some of the timelines outlined in the report could be sped up.

The American Conservation Coalition (ACC), a Republican-leaning group that advocates for conservative solutions to climate change, is also supportive of aspects of the report. “There’s elements of it that we agree with and that I think many Republicans could agree on, too,” Quillan Robinson, vice president of government affairs at ACC, told Grist, naming carbon capture and investments in new energy technologies as examples of proposals that could garner bipartisan support. But he noted that the committee’s report was introduced without input from the Republican minority on the committee. “The whole purpose of the committee was to bring Republicans and Democrats together and develop some common ground policies to charter a path forward,” he said. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy and nine other Republican members of the House recently backed a climate plan put out by ACC that also calls for net-zero emissions by 2050, a surprising step that indicates Republicans may be amenable to climate proposals that come from their own side.

Ricketts isn’t so sure that the reason why the Republicans minority is absent from the report is because it was snubbed by committee Democrats. “The leader of the Republican party doesn’t just believe that climate change doesn’t exist, he called this pandemic that has killed 120,000-plus Ameircans a hoax,” Ricketts said. “It’s unfortunate but it is a reality that only one party believes in not only confronting this crisis but that it exists at all.”

Regardless of how the report came together, one thing is clear: Democrats will have a hard time getting its wide-ranging and ambitious policy proposals passed even if they regain a majority in the Senate and put Joe Biden in the White House. Biden’s climate plan as it stands proposes investing a modest $1.7 trillion in clean energy spending. The House climate committee’s report doesn’t put a price tag on its recommendations, but in terms of scope it looks similar to Sanders’ climate plan, which would cost $16 trillion.

Still, some groups think it could go even further. “With less than 10 years to keep warming at below 1.5 degrees C, the plan’s targets for phasing out emissions need to be stronger,” 350.org’s associate director of U.S. policy, Natalie Mebane, said in a statement. “Specifically, these plans need to go further on regulating and phasing out fossil fuel production with clear target dates for the elimination of all fossil fuel expansion and subsidies.”

On the other side of the aisle, Republicans are already sharpening their knives. “Democrats’ My Way or the Highway bill is nothing more than a liberal wish list,” Representative Don Young of Alaska tweeted on Tuesday afternoon.