Imagine a green future for a hot second (no pun intended). The United States and the rest of the world have taken substantive action to slow (and even reverse) climate change. Crisis averted! You’re probably envisioning a lot of the following: snazzy yet affordable electric cars, smog-free city skylines, and an electrical grid powered by sweet, sweet, renewable energy.

Well, you likely don’t need the staff of Grist to tell you that the nation is nowhere near approaching that eco-friendly dreamscape.

In fact, the U.S. is currently on a path away from that green dream. Bigly. The Trump Administration is in the process of finalizing the country’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. (It will shortly become the only one in the world that contributes more than 2 percent of global emissions without being a member of the landmark climate pact). Emissions have been on the rise again after years of incremental dips — slowed this year only because of a deadly pandemic. And the nation’s most vulnerable communities are routinely forced to reckon with environmental contaminants, extreme weather, and industrial pollution.

If a couple of intrepid aliens dropped by to observe a Congressional hearing on climate change, knowing that humanity’s survival hinged on finding a solution to rising temperatures, they would hurry back to their home planet under the impression that Earth was doomed.

It doesn’t have to be this way. That green dream could be a reality — and for the most part, we know what we need to do to bring it to life.

Below, you’ll learn about eight tools lawmakers could leverage to make America great on climate change. These are interventions that already exist, and concern everything from your home to your local transportation system.

All we need to do is reach out and grab them.

Ditch the gas guzzlers

In a world of Priuses, Leafs, Bolts, and a growing number of Teslas, you’d think that the national average for gas mileage would be higher than it is: a measly 26 miles per gallon.

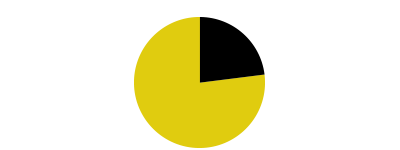

Consumer Reports, 2019

That’s not very efficient. And it’s partly why, in 2018, transportation produced nearly 30 percent of the U.S.’s global warming emissions — more than energy or any other sector, with most of it coming frompassenger cars and trucks.

The good news: The vast majority of Americans say they want the federal government to increase fuel efficiency standards for all types of vehicles.

In the short term, hybrids and plug-in hybrids are available to satisfy the needs of those who want — and can afford — more efficient rides. They easily meet or surpass California’s stricter fuel-efficiency standards, with some models reaching over 56 mpg.

Eventually, if the federal government follows California’s lead, our roads could be filled entirely with electric vehicles. Emissions-free autos are already beginning to take off, with sale prices falling and current models able to go as far as 141 miles using the same amount of energy in one gallon of gasoline.

But fully electric vehicles still make up less than 2 percent of annual car sales. An analysis from the International Energy Agency found that policies like fuel mandates could drive EVs to make up 30 percent of all U.S. auto sales by 2030 — an impressive rise, but still not enough to meet the most aggressive climate targets.

Proposals do exist to better meet the moment. In a report released this summer, the Democratic House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis proposed that the federal government create an ambitious greenhouse gas emissions standard for light-duty vehicles and trucks to reduce pollution by at least 6 percent each year for five years, beginning in 2026. The Environmental Protection Agency already has the authority to do this under the Clean Air Act.

The House committee also recommended action from Congress, where lawmakers could establish a zero-emissions vehicle sales standard, requiring all vehicles sold to be emissions-free by 2035. Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden’s campaign has floated a similar sales standard for light- and medium-duty vehicles, which would complement “annual improvements” for larger automobiles.

— Joseph Winters

Not-so-extreme makeover: home edition

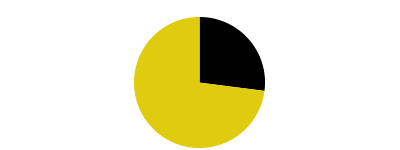

Little-known fact: Buildings are responsible for just over a third of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. About 10 percent of all emissions come from directly inside them, such as whenever we fire up a gas stove for a meal or flip on the heat to keep warm. Not only that but burning fossil fuels inside our homes isn’t great for our health.

Climate Nexus / Yale Program on Climate Change Communication / George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication, 2020

Like trading in your beat-up Chevy Impala for an all-electric Bolt, there’s a straightforward solution: Replace boilers and hot water heaters with electric heat pumps. Swap gas-powered stoves for snazzy new induction cooktops.

Improving energy efficiency is also a way to cut down on emissions from buildings. Whether your heating system is powered by electricity or gas, or if you live in an old, drafty house that needs insulation, you’re probably using more energy than you need to — both the heat and your dollars are slipping through the cracks. (For low-income Americans, the cost-burden of an inefficient home can be as high as 26 percent of their earnings.) Sealing up cracks and helping people replace old appliances would lighten the load on their wallets while cutting emissions and, most crucially, reducing demand on the electric grid so we can actually meet all our energy needs with clean sources.

So where do we start? Congress could increase funding for the Weatherization Assistance Program that helps low-income households pay for energy-efficiency upgrades. It could also strengthen efficiency standards for buildings and appliances, and increase and extend tax credits for retrofits.

Most of the action will likely happen at the state and local level, through incentives, rebates, and pilot programs that help people cover the cost of all these upgrades, along with new laws and updated building codes designed with an eye to increased energy efficiency.

— Emily Pontecorvo

Get on the bus!

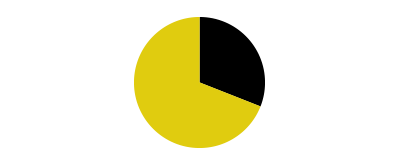

If the U.S. starts taking climate change seriously, we’ll have to become much less dependent on cars (even if they are more efficient). A staggering 75 percent of Americans drive alone to work. And even before the pandemic hit, ridership on buses, trains, and subways appeared to be on the decline. According to the American Public Transportation Association, 45 percent of Americans couldn’t use public transportation even if they wanted to — because of where they live.

Data for Progress, 2020

Taking climate change seriously will require a redesign of our country’s transportation infrastructure. In other words, we’ll have to find a way to get people out of their cars. In the early 2020s, that will mean taking public money away from building new highways that encourage people to drive more, and using it to expand the country’s existing bus, train, and subway systems, especially for rural communities and areas that have traditionally been denied transit access. Do all this, and by 2030, the majority of Americans will live within walking distance of public transportation.

Sound like a plan? It’s one devised by the advocacy group Transportation for America as a way to meet international climate targets. Activists see public transit as a huge opportunity — not only to slash emissions from the country’s biggest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions, but also to create jobs and fuel the American economy. One analysis found that every $1 billion invested in transit can generate $5 billion in economic returns, creating and supporting roughly 50,000 jobs. According to the Blue Green Alliance, fixing up our existing road and transit systems could generate 6.6 million jobs within 10 years.

So how do we arrive at the future that Transportation for America and others envision? The Biden campaign has proposed using federal funds to provide all Americans in cities of more than 100,000 people with “quality public transportation” by 2030. In a report this summer, House Democrats recommended at least doubling annual funding for new transit projects and implementing a minimum emissions-per-mile performance standard for vehicles traveling on the National Highway System. If a state’s emissions exceed those standards, it would have to use its federal highway money toward projects to decrease emissions.

— JW

No fossil-fuel worker left behind

If and when the nation ditches fossil fuels, what happens to the nearly one million people who work in the oil and gas industry? It’s a reasonable question, and one that’s become a sticking point that Republicans, fossil fuel lobbyists, and some unions often leverage to derail much of the talk about expanding the country’s renewable energy.

Climate Nexus / Yale Program on Climate Change Communication / George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication, 2020

Right now, the systems to help fossil fuel workers find jobs in the green energy sector aren’t in place yet. But roadmaps to accomplish such an evolution do exist.

In June, a group of 80 local, regional, and national organizations published the National Economic Transition Platform, a raft of policy recommendations for federal policymakers designed to help fossil fuel workers shift to a green-energy economy. The plan recommends putting former coal miners to work on cleaning up coal sites and abandoned mines and restoring local water resources, as well as creating new jobs in energy efficiency retrofits for residential and commercial buildings.

There’s been some discussion of this issue in Congress, as well. Senator Tammy Duckworth from Illinois, a Democrat, introduced a bill this July that simultaneously seeks to revitalize communities devastated by the decline of coal and restore the surrounding environment. The Marshall Plan for Coal Country Act would also boost the federal minimum wage to $15 and provide Medicare for coal workers who have lost their jobs.

Joe Biden’s latest climate plan picks up where Duckworth’s bill leaves off. He proposes creating a Task Force on Coal and Power Plant Communities, which would help the families who wind up out of work in a clean-energy transition access federal funds for recovery efforts, partner with community colleges for training opportunities, and find jobs repairing local infrastructure. Biden’s plan also calls for an entirely new class of jobs and job training in climate-resilient industries (think: coastal restoration, sustainable infrastructure design, and tree planting in cities).

On the campaign trail in 2016, President Trump accused Democrats of abandoning oil, gas, and coal workers. But polling shows people are open to building a green economy, as long as it doesn’t leave Americans behind.

— Zoya Teirstein

Protection for the day after tomorrow

More and more Americans are waking up to the fact that we’re going to need to shore up our homes, neighborhoods, and communities against the effects of planetary warming. Low-income and vulnerable minority areas already dealing with the fallout from extreme weather are going to need even more help.

Climate Nexus / Yale Program on Climate Change Communication / George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication, 2020

Each region of the U.S. faces its own unique set of disasters. And a simple formula can help states prepare for what’s coming: Plan + funding = protection. In other words, state governments need to figure out how to protect their residents, and the federal government needs to do what it does relatively well: dole out disaster-relief dollars.

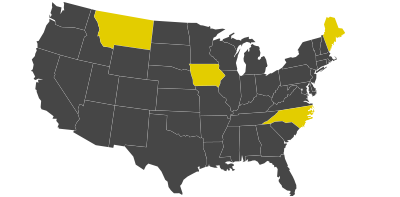

Some states are already leading the way. This summer, North Carolina passed the NC SECURE Act, which streamlines the funding and permitting of projects that store floodwater and reduce the risk of inundation. The legislation calls for a mix of federal disaster relief funds and state dollars to create a grant program to prioritize natural solutions to flooding, like restoring wetlands and directing water to green space that can soak up floodwaters.

Virginia is planning to use money generated from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic’s cap-and-trade program, to fund climate resilience projects. The commonwealth joined the initiative this year and expects to generate $100 million annually from the program, with $45 million of it slotted for coastal resilience and community flood preparedness.

Even when funding flows after a disaster, plenty of people are left out. For example, there are 90,000 fewer Black New Orleanians now than there were before Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005. And a survey of post-Hurricane Harvey Houston showed 50 percent of lower-income respondents said they weren’t getting the help they needed, compared to 32 percent of higher-income respondents.

Thus, a truly equitable plan to beef up disaster preparedness should allocate a certain portion of the funds to the nation’s most vulnerable communities.

— ZT

Greening the grid

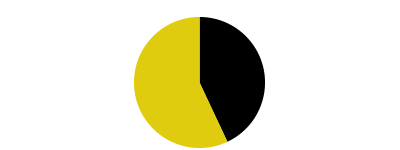

The U.S. still runs on dirty power. Fossil fuels provide 63 percent of the country’s electricity. In some states, like West Virginia and Wyoming, the grid is powered almost entirely by coal.

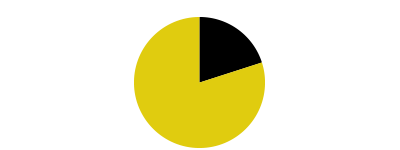

Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019

The solution, according to some policymakers, is obvious: The federal government should require power companies nationwide to draw their energy from clean energy sources (think wind, solar, nuclear, geothermal, and hydropower). Thirty states and three territories already mandate the use of renewables in the electricity grid. And — surprise surprise! — they also tend to have lower carbon emissions than their neighbors. But most of them set a relatively low bar for renewable generation, aiming to make it 15 to 25 percent of their overall energy mix.

A new generation of advocates wants to raise it much, much higher: They want all of the country’s electricity to come from pollution-free sources by 2035. Biden has thrown his support behind the goal, amid pressure from youth activists and his former rival, Senator Bernie Sanders. The House climate crisis committee aims to erase emissions from electricity slightly less aggressively, by 2040.

Hitting either of these goals would mean a lot more solar panels and wind turbines nationwide — and a lot fewer coal and natural gas plants. But here’s the rub: Simply setting a target for clean energy won’t be enough.

To fully kick dirty-but-reliable fossil fuels off the grid, we need new technology for storing energy for long periods of time and new methods for generating high heat for industrial processes, like cement manufacturing. That’s why spending big bucks on research and development is key. Biden’s plan, for example, invests $400 billion over the next decade on solving these problems.

Then there’s a third tool in the clean energy Swiss army knife: tax incentives. The credits the wind and solar industry rely on to finance new projects are about to expire. House Democrats want to extend those incentives for a few more years — and eliminate some of the tax breaks that give oil and gas companies an unfair advantage and keep fossil fuel prices competitive with renewables. Other policy wonks have suggested reviving an Obama administration program that offered grants instead of tax credits to really kick the renewable industry into high gear.

— SO and EP

Price carbon out

Once upon a time, putting a price on the carbon content of fossil fuels — much like we tax cigarettes or alcohol — was the policy of choice for both Democrats and Republicans hoping to curb dangerous climate change. According to economists, the government could just slap on an extra cost for burning fossil fuels, and then step back and watch emissions plummet.

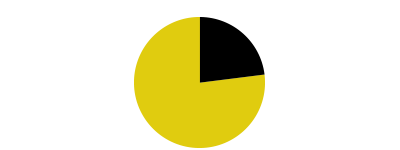

Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2020

Nowadays, taxing carbon isn’t quite as popular. Democrats prefer to focus on big spending and regulations, while a lot of Republicans ignore the overheating planet entirely. Those Republicans who do accept the reality of climate change, however, still tend to be fans of pricing carbon: James A. Baker, George P. Shultz, and other old-school Republicans have released a comprehensive carbon tax plan that has won support from corporations and economists alike.

A tax on carbon pollution could play a big role by helping to cut emissions across the economy — not just from the electricity grid. Proposals floating around Congress suggest taxing carbon dioxide emissions at $15 per ton (equivalent to about $0.13 per gallon of gas), and then ratcheting the price up every year.

The only sticking point is what to do with all of that cash collected. A carbon tax would provide hundreds of billions of dollars in government revenue every year — and legislators are divided over how best to use it. Because some of the costs would fall on taxpayers — through, for example, a price hike at the pump — policymakers have suggested a “revenue-neutral” tax, where per-capita proceeds would be returned to households or offset by decreases in the income tax. Others suggest reinvesting the revenue into the development of clean energy technologies, like solar and wind, or supporting communities that have been hard hit by fossil fuel pollution.

If the tax is high enough, it could be critical to cutting America’s carbon footprint. Forty countries around the world have managed to implement some form of carbon pricing, and even though many have yet to fulfill their promise, a carbon tax in the U.K. has helped emissions in that country reach their lowest levels since 1890.

— SO

Make vulnerable communities resilient

The U.S. doesn’t have a great track record of protecting people living in places choked by pollution and more likely to get hit hard by extreme weather. Entrenched structural systems, think redlining and being ignored by local politicians, lead to more pollution winding up in low-income enclaves and neighborhoods of color — and leave them vulnerable to the consequences of a warming climate.

Data for Progress

A few policy changes could make these frontline communities resilient. Governments at all levels can, for example, pass laws to reduce methane emissions from natural gas operations, which would improve air quality and slow climate change. (Methane is a more harmful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.) It would be a boon to public health.

Take the populations living along the Gulf Coast, for example. Just this summer, industrial coastal cities in the South were hit with hurricanes and tropical storms that brought torrential rain and a series of floods. Hurricane Laura, a category 4 storm, pummeled the petrochemical hub of Port Arthur, when it made landfall over Texas at the end of August.

Many low-income communities of color were left with the option of either weathering the storm at home despite being warned to evacuate, or leaving their homes and risk being exposed to COVID-19 and thick air pollution. Shutting down plants in preparation for potential storms isn’t enough to keep those communities safe — nearby chemical plants and oil refineries continue to spew harmful chemicals in the process of going offline.

Environmental justice organizations have been laying out ways to protect at-risk residents. A focus on clean energy and resilience measures, from seawalls to community evacuation protocols, would not only limit the risk from future storms in vulnerable neighborhoods but also reduce their exposure to pollution. In his climate plan, Joe Biden promised to invest historic levels of funding toward clean energy, aggressively limit methane pollution from the oil and gas industry, and ensure vulnerable communities benefit from a shift to a green economy.

Imagine a country where climate change isn’t the crisis it absolutely is right now — and all residents can feel safe to breathe and move around, inside and outside their neighborhoods.

— Angely Mercado

Will Americans elect officials to federal, state, and local governments to ensure the nation does its part to slow climate change? It’s 2020, the planet is on the ballot, and Grist is detailing the stakes.