Before Judge Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed by the Senate on Monday, she had spent a month as a nominee saying basically nothing. In today’s world of highly partisan appointees to the Supreme Court, nominees have learned to keep their opinions buttoned-up: Barrett’s favorite phrase during the hearings was “no hints, no previews, no forecasts.”

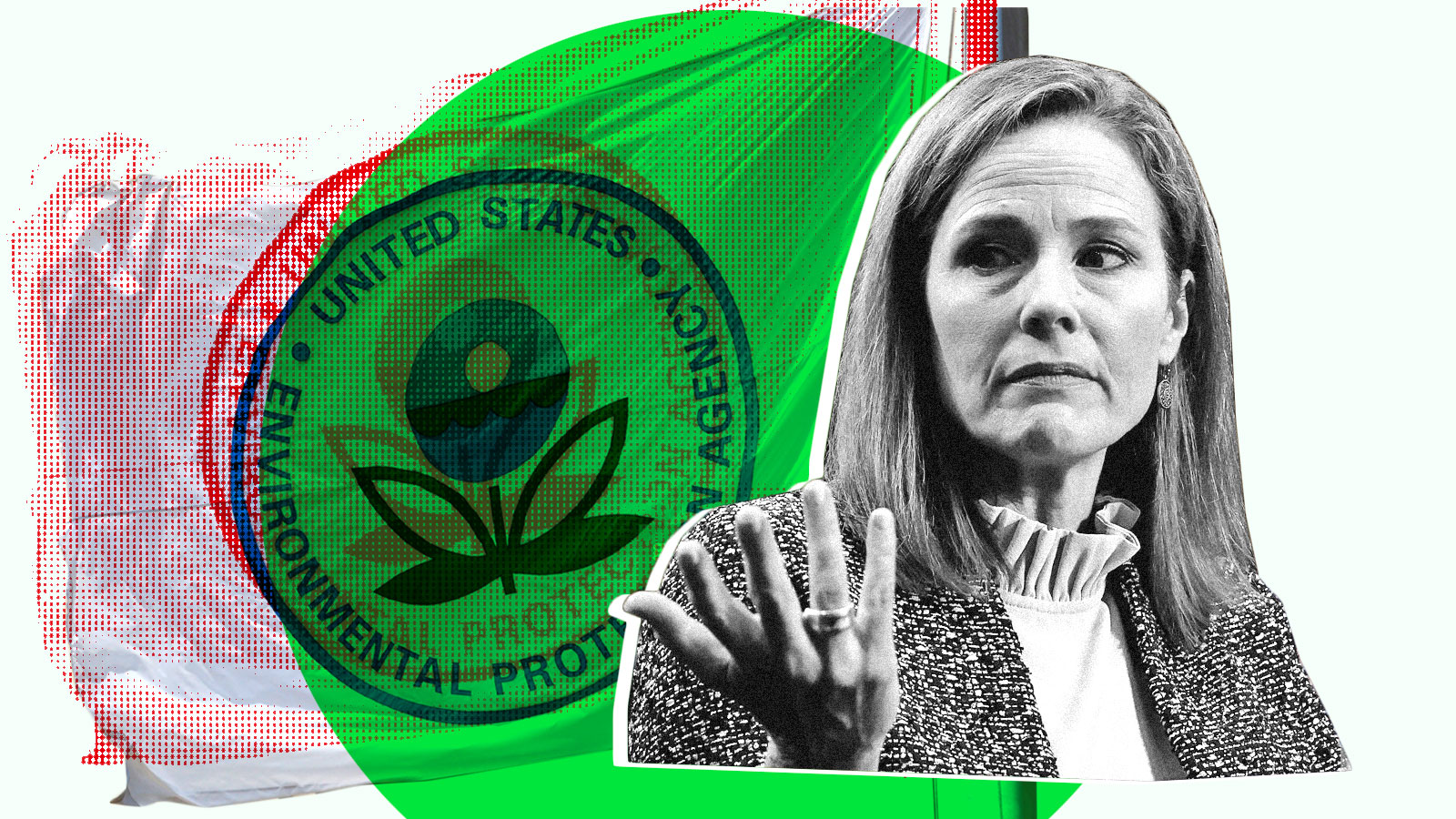

When it comes to climate change, however, what Barrett didn’t say may prove just as important as what she did. Barrett refused to acknowledge the science of global warming during her hearings. In an exchange with Senator Kamala Harris of California, Barrett said that she didn’t want to weigh in on a “very contentious matter of public debate,” causing scientists everywhere to roll their eyes. But for those calling for action on global warming, the real concern about Barrett getting a seat on the highest court isn’t her willingness to toe the Republican party line on climate vagueness. It’s how the new Supreme Court could be poised to strike down even the most bipartisan climate laws — thanks to a growing conservative movement to boost something known as the “nondelegation doctrine.”

“The idea is that Congress shouldn’t delegate too much power to the executive branch,” said Michael Gerrard, a professor of climate change law at Columbia University. “So Congress couldn’t just say, ‘EPA, we want you to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent and you figure it out.’ They have to give a whole lot of specific details on how this would work.”

There are two major paths to cutting down the country’s runaway carbon emissions. The first is through a president’s executive action, which President Barack Obama tried (and failed) to do in his second term. The other has much more potential but is exponentially more difficult: passing an actual climate bill through Congress. In all likelihood, that would take months of political wrangling, and would require Democrats to win back the Senate and either work around — or abolish — the filibuster.

But even if Congress manages to pass such landmark legislation, there might be a problem. According to the doctrine, Congress shouldn’t let other branches of government do its work: That is, it shouldn’t delegate power elsewhere. That all sounds well and good. But the problem, according to Julian Mortensen and Nicholas Bagley, law professors at the University of Michigan, is that almost all government activity in the country relies on Congress handing off tasks to other branches. Congress might pass a law, for example, requiring the EPA to set pollution standards that are “requisite to protect human health,” or telling the Justice Department to regulate drugs to protect “public safety.” It’s unreasonable to expect Capitol Hill to have the time, or the expertise, to get into the nitty-gritty of every single government regulation.

That’s partly why the principle hasn’t been used by the Supreme Court since 1935, when the court struck down two provisions of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal for awarding too much power to the White House. (Roosevelt, frustrated, then threatened to pack the court, and the justices eventually backed off.) Since then, the Supreme Court hasn’t invoked nondelegation in any major cases; in oral arguments in 2014, Justice Anthony Kennedy called it “moribund” — just about dead.

Now, however, with more and more constitutional “originalists” — those who think that the Constitution should be interpreted according to its meaning when ratified back in 1790 — creeping onto the Supreme Court, the tide is turning back towards the doctrine. “Five justices have announced explicitly, specifically, that they’re prepared to revisit the doctrine, and to police it more aggressively,” said Lisa Heinzerling, a professor of law at Georgetown University.

In 2015, Justice Clarence Thomas, for example, blasted the “vast and unaccountable administrative apparatus” in a dissent. In 2017, Justice Neil Gorsuch told the Federalist Society: “Our founders did not approve of lawmaking by bureaucrats by fiat.”

Barrett’s opinions on delegation remain murky, but she is both an originalist, like Scalia and a former member of the Federalist Society, which has zeroed in on the doctrine in recent years. And even without Barrett,the court has a majority ready to revive a principle that has been defunct for decades.

If that happens, environmental regulation could be the biggest loser. The overwhelming majority of laws designed to cut air pollution or clean up the country’s waters count on the EPA to determine what levels of toxins are unhealthy, or which technologies to use to cut dangerous emissions. With a majority of the Supreme Court adhering to this doctrine, that authority could be in jeopardy — and so could future laws to slash carbon dioxide emissions.

“They will be particularly looking for broad language authorizing agencies to act on important problems,” Heinzerling said. “And that looks a lot like climate to me.”

It’s hard to say exactly what test a new Supreme Court would use to determine if Congress is handing over too much power to agencies like the EPA. Some previous rulings — like the landmark case of Massachusetts v. EPA, in which the court found that the EPA had the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles — will probably be safe. New regulations on greenhouse gases, however, would be fair game. Previous opinions from Gorsuch and Kavanaugh made the case that Congress shouldn’t delegate “major” or “important” policy decisions to the executive branch. But what counts as a major decision? The “safe” level of choking particulate matter near a public school? How exactly public utilities should cut their greenhouse gas emissions to zero?

According to Gerrard, if a Democratically controlled Congress wants to pass legislation limiting global warming — such as Joe Biden’s proposed plan to eliminate carbon emissions from the electricity grid by 2035 — it will have to be extremely detailed and specific, to avoid court challenges. That means not just telling the EPA to cut greenhouse gas emissions, but also identifying specific pathways and technologies to do so.

The hitch is that the more detailed the law, the harder it will be to get through Congress. “They’re scolding and hectoring Congress for not making the tough decisions, but at the same time they’re proposing to make it tougher to make the tough decisions,” Heinzerling told Grist. “It’s just insane what they’re suggesting. It’s a barely disguised hostility to an act of government.”