Yesterday, I wrote about how African-American politicians are being directed by the fossil fuel industry and electric utilities to reject certain solar power options for the sake of low-income, black families. The argument from those utilities is that households that produce their own solar-based electricity, through net metering, will raise electricity costs for non-solar households, and chiefly those of low-income, because the solar producers aren’t paying their fair share to take care of the grid. (Grist’s own David Roberts wrote an excellent set of explainers on this solar beef last year.)

When the debate around solar net metering is presented that way, it’s not difficult to see why it could possibly become a net deficit for low-income households. This is how Edison Electric Institute, a trade association for utility shareholders, framed the issue for the National Policy Alliance, which consists of black elected officials large and small. The result was that NPA passed an unfavorable resolution on net metering that it says it will pass on to the White House.

I believe that the NPA members who voted against solar net metering policies probably did so out of a genuine desire to protect long-time disadvantaged African-American communities. But the simple math logic used to claim net metering will harm black households fails to figure in the calculus of the utility companies’ carbon pollution that is presently devastating black households. It also fails to calculate all of the utilities’ inflated costs for electricity production that already hike up electric bills.

First, to address the undergirding argument of the utility companies, it’s not entirely true that solar producers increase grid costs without contributing to it. Because of the energy that solar producers add to the system, utility companies get to produce and distribute that much less electricity throughout the grid. In essence, solar homes are bringing sand to the beach, and to paraphrase Jay Z, their “beach is better” — it’s sunnier, cleaner; they don’t need the sand of the old polluted beaches that have been charging visitors too much at the entranceway, anyway.

As Robert Robinson of DC Solar United Neighborhoods (DC SUN), a group of neighborhood solar co-ops, explained it to me: “We already know that there are over 20,000 people [in D.C.] who apply for electric bill assistance annually, not because money is being wasted on solar — it’s because the cost of electricity from fossil fuels is going up and this primarily affects low-income people.”

[grist-related tag=”solar-disconnect” limit=”5″]

One way to understand the role of utility companies in creating high electricity rates, and how solar can impact that, is to look at the music recording industry. Record companies once regularly allowed for hot-air balloon budgets to create products for music consumers. They’d pay Timbaland or Dr. Dre a few million dollars for a beat and then a few million more for Hype Williams or David Fincher to direct the videos for Viacom’s music channels. They determined whether a million of an artist’s CDs were shipped to stores or just a few thousand, based on sketchy math about fans’ demand. This is part of why you paid as much as $17.99 for a CD at The Wall back in the day.

But then Napster happened. Artists began using programs like Pro Tools and Garage Band to make their own beats, and used similar editing apps to cut their own videos. They no longer needed MTV or The Wall because of Myspace, YouTube, and Paypal. Record companies went ballistic, said the music industry would implode, claimed music costs would go up, and yada, yada. But it never happened. Instead, the record companies calmed down. They adjusted their inflated budgets and diversified their revenue streams.

Since music production was democratized, we now have a better understanding of the true costs for making and distributing music. Customers can get all the music they want for less than $10 a month through iTunes and Spotify. No one is paying $20 million for a beat by Dre; he now makes his money through his streaming service, Beats by Dre.

It’s not exactly apples-to-apples. As Dave Roberts pointed out to me, artists can YouTube their work without a record company’s consent, but solar producers can’t feed their electricity to the grid without utility companies monitoring it. And the utilities still get to decide the pay rates. That’s one of the biggest problems with utilities: Billpayers don’t know what energy distribution costs are and how those compare to actual demand and consumption, because there’s little transparency. Utilities just set the budgets — real demand be damned — and make us pay.

As Craig Lewis, executive director of the nonprofit Clean Coalition, explained it recently in a HuffPo op-ed:

Currently, electric utilities make money by building and maintaining centralized power plants and large transmission lines. This market structure is known as a cost-of-service because utilities are given guaranteed returns on the amount of money they invest to provide electric service to customers. Once logical, this structure now encourages utilities to favor expensive investments even if new, affordable solutions — such as energy efficiency, demand response and local renewable generation — offer a cheaper alternative. This has led to an inefficient and overly expensive electricity system. For example, New York uses just 60 percent of the electricity its system is capable of generating. And New Yorkers pick up the tab, through their utility bills, for this oversized system.

In other words, you can’t drive up supply and costs on electricity for consumers and then suddenly, conveniently become sympathetic to the minimum-wage class when solar producers pull up the curtains.

Also, the argument that solar net metering financial burdens poorer ratepayers is actually somewhat exaggerated. Recent studies have shown the opposite effect: When structured correctly, net metering can spread economic benefits across communities, including to those who can’t produce their own solar power. A study from Crossborder Energy on net metering policies found that it led to over $92 million in energy savings in California. Mississippi, one of the few states with no net metering policies, studied the matter and found that from “a Total Resource Cost perspective, solar net metered projects have the potential to provide a net benefit to Mississippi in nearly every scenario and sensitivity analyzed.”

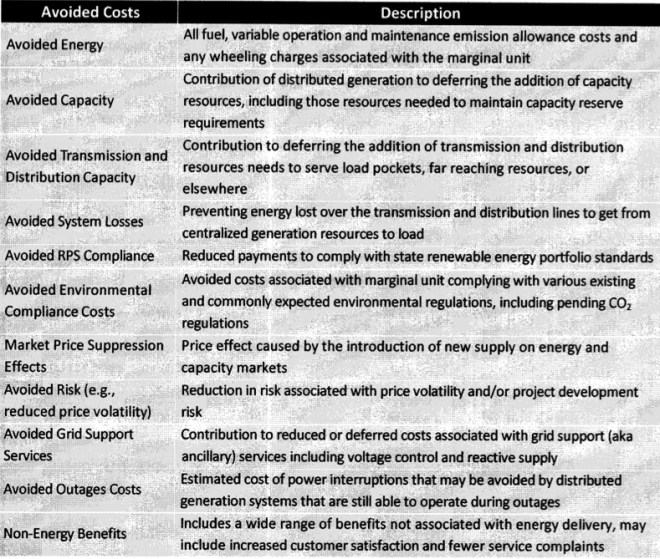

What are these benefits? Well to begin with, electricity costs start to come down when you account for all of the energy costs that utility companies get to avoid thanks to the solar generators. The Mississippi study lists these:

Add community-based solar projects into the mix and it allows for even broader distribution of solar benefits across neighborhoods. In D.C., the city council passed the Community Renewables Energy Act last year, which allows renters, tenants, and residents to access solar energy even if they don’t have solar panels on their own houses and apartment buildings. This helps offset the monthly energy bills for anyone connected to a “community renewable energy facility.” DC SUN is working with environmental justice groups and the DC utility Pepco to help improve upon the benefits of this law.

Similar community solar benefits have been created in the Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans, and California has programs in place to include low-income households in the solar explosion. The Center for Social Inclusion is keeping tabs on other community solar projects like it across the nation as examples of what energy democracy look like — literally more power to the people.

“A decrease in carbon reliance and in increase in renewables will benefit all of us in the sense that it will require less dirty energy pollution and less use of carbon resources,” said Anthony Giancatarino, Director of Policy and Strategy for The Center for Social Inclusion, when I discussed it with him. “Those are benefits for all — regardless of how solar or wind is generated.”

As with any policy, equity has to be built into any net metering program in order to fully realize its full benefits. At the very least, this means states can’t obstruct the paths created for community-wide rewards and ownership. This blockage is currently happening in Nevada, where the state is considering repealing its net metering laws, despite the fact the state’s own net metering study found that it brings $36 million in benefits to its residents. Jeanette Williams, president of the NAACP’s Tri-State Conference of Idaho, Nevada and Utah wrote in support of keeping the net metering laws in a Las Vegas Sun op-ed this past Sunday.

“The growth of a new energy sector is an opportunity for the black community to reap the economic benefits we have previously been denied,” wrote Williams.

The NAACP’s support on this shows that not all black leadership is misinformed on this issue. No one is saying that solar net metering will eliminate the racial wealth gap or that it will solve racism. It is not an automatic boon to poor communities of color; but neither is it fair or accurate to conclude that it is an automatic failure to them.

Why an organization like the National Policy Alliance, which has the ear of President Obama, would bind its constituents to the industries of pollution rather than help ease their transition to the industries of better health is the real head scratcher here.

In the next part of this series, I’ll post my interview with the Alliance’s executive director Linda Haithcox, who explains what the thinking was behind the anti-net metering resolution.

Want more on net metering? Read this next: This ambassador for black politicians argues that solar drags down African Americans