Image: National GeographicToday, the United Nations announced that the world’s population will reach an historic 7 billion people on Oct. 31, 2011. World population hit 1 billion people in 1804. It took 123 years to add the next billion, but less than a century to cruise past the next four billion — from 2 billion people in 1927 to 6 billion people in 1999.

Image: National GeographicToday, the United Nations announced that the world’s population will reach an historic 7 billion people on Oct. 31, 2011. World population hit 1 billion people in 1804. It took 123 years to add the next billion, but less than a century to cruise past the next four billion — from 2 billion people in 1927 to 6 billion people in 1999.

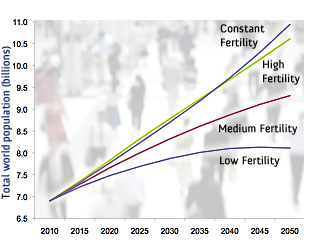

The U.N.’s Population Division also projected that the world will reach just over 10 billion by 2100, a number based on many uncertain assumptions about the future. Demographic projections are often mistaken for predictions, but they only show us what would happen if today’s demographic trends follow specific paths. And we all know that change is inevitable. We also know that if millions of women continue to have problems accessing contraception, and lack economic and educational opportunities, these numbers could go up even more.

The U.N.’s projections — presented in the 2010 revision of World Population Prospects — offer only a few scenarios and are based on potential changes in policies, services, and behaviors. They do not account for all the realities we see on the ground, where in some countries, women are not getting the family-planning services they want. The decisions and policies we make today will ultimately determine whether our numbers climb to anywhere from 8 billion to 11 billion by mid-century.

The U.N. projections show some striking changes in countries’ projected populations for 2050. Forty countries’ populations are projected to at least double in the next 40 years, including Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen. Nigeria’s population for 2050 is projected to jump by 150 percent, from 158 million to 390 million.

Many of these increases in projected population, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa, are due to persistently high fertility rates. The projections assume that the average number of children per woman will begin falling in such countries, but this is often a rosy assumption. For example, Nigeria’s fertility rate for 2010-2015 was previously projected to be 4.8 children per woman, but has now been revised to 5.4. This difference contributes to a much larger total population by 2050.

Still, the assumptions built into the projections for many high-fertility countries would require major increases in the use of family planning. Nigeria’s fertility rate, measured [PDF] at almost six children per woman in 2008, is projected to fall to slightly over three children by 2050. This is highly unlikely if current trends continue, because only 10 percent of married women in Nigeria use effective contraception, while 20 percent want to avoid pregnancy but aren’t using family-planning services. Until their health-care needs and rights are fulfilled, the demographic future the U.N. has projected for Africa’s largest nation seems too optimistic.

U.N. population projections — will we follow the high, medium, or low path?The projections may also be optimistic for countries at the opposite extreme, with very low fertility rates. Fertility rates in Japan, Korea, and Russia have declined significantly since the late 1980s. Their rates are now 1.4 children or less, which would lead to significant population decline. The U.N. projects that their rates will rise by at least 30 percent by 2050, but that may be based on faulty assumptions. Some researchers believe these very low fertility rates are linked to gender inequities and difficulty balancing work and family. If societies don’t become more woman-friendly and family-friendly, these fertility rates may not rise. As it turns out, a lack of opportunities for women may be the driving force behind both very high and very low fertility rates.

U.N. population projections — will we follow the high, medium, or low path?The projections may also be optimistic for countries at the opposite extreme, with very low fertility rates. Fertility rates in Japan, Korea, and Russia have declined significantly since the late 1980s. Their rates are now 1.4 children or less, which would lead to significant population decline. The U.N. projects that their rates will rise by at least 30 percent by 2050, but that may be based on faulty assumptions. Some researchers believe these very low fertility rates are linked to gender inequities and difficulty balancing work and family. If societies don’t become more woman-friendly and family-friendly, these fertility rates may not rise. As it turns out, a lack of opportunities for women may be the driving force behind both very high and very low fertility rates.

The surprising assumptions underlying some countries’ fertility rates reflect one of the key features of the population projections. In the past, the projections were constructed using a technique that, in the U.N. medium fertility projection, assumed all countries would move toward a universal fertility rate of 1.85 children per woman. High and low fertility projections only varied from the medium by 0.5 children per woman in either direction.

This universal rate was highly improbable among countries at the demographic extremes, and the U.N. has now recognized that its past projections did not allow for unpredictable demographic transitions within individual countries. Uganda is a dramatic example of this. The previous revision of the U.N.’s World Population Prospects showed that the country’s fertility rate had fallen by about half a child per woman — less than 8 percent-between 1950 and 2010. Yet that report projected that the country’s fertility rate would decline by 60 percent, to less than three children per woman, by 2050.

Starting with today’s new set of projections, the U.N. has shifted to a “probabilistic” model for its medium-fertility scenario. This allows the pace of each country’s fertility decline to be calculated individually, based on new estimates of historic fertility rates, allowing for much more variance across countries. The new method also assumes that fertility rates will eventually balance out around 2.1 children per woman, a level where couples would “replace” themselves in the population, rather than 1.85. And the projections now extend out to 2100, and incorporate life expectancies ranging as high as 90+ years.

These U.N. changes add greater nuance to population projections, but they are still far from a crystal ball. Policymakers must take the next step and invest in family planning and education for the projections to ever meet reality.

—–

Also check out:

- 8 things you can do about population

- Watch author Jonathan Franzen talk about overpopulation

- Q&A with Jonathan Franzen about population & other green issues