A burst of gunfire rang through a forest on the edge of Atlanta, Georgia, on the morning of January 18. Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, whose chosen name was Tortuguita (Spanish for “little turtle”), had been shot and killed by police officers, becoming the only known person killed by law enforcement during an environmentalist act of land defense in the modern U.S., according to experts Grist consulted.

Tortuguita was part of a loose-knit group continuously occupying the woods to stop trees from being felled by construction of a sprawling police training center known to activists as Cop City. In 2021, with little public input, the Atlanta city council approved plans for the $90 million Public Safety Training Center on the city-owned former site of Atlanta’s prison farm, which the trees had reclaimed and had previously been included in plans for a revamped parks system. (The activists call the area the Weelaunee Forest, a name from the Muscogee people who were violently forced out of the area 200 years ago.)

Although some members of the transient and leaderless group had damaged property in apparent attempts to stymie construction, many just camped, hoping their refusal to move out of the way of the trees would prevent them from being cut down and replaced by firing ranges and a mock city where police would conduct riot training.

That morning, members of a multi-agency law enforcement task force had moved through the woods toward Tortuguita’s tent. According to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, Tortuguita fired first, using a handgun the 26-year-old had purchased, and struck a Georgia State Patrol officer, who was hospitalized. No civilians appear to have witnessed what happened, and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation says no body cameras captured the incident. In life, Tortuguita spoke often (and publicly) of the virtues of nonviolence, so their friends and fellow activists doubt the state’s story.

“We have no reason whatsoever to trust the narrative that’s been given,” said Kamau Franklin, founder of the local group Community Movement Builders, which organizes with Black communities in Atlanta and opposes the police training center, citing other high-profile police killings around the country in which official narratives have fallen apart.

While the environmental nonprofit Global Witness has documented over 1,700 killings of land defenders worldwide over the past decade, the organization currently only lists one in the U.S. over the same time frame: a fisheries observer who disappeared at sea under circumstances that suggested foul play in 2015.

On Thursday, Governor Brian Kemp declared a state of emergency in response to protests Saturday night sparked by Tortuguita’s death, during which participants threw rocks, broke windows, and burned a police car. Kemp’s order, effective until February 9, allows up to 1,000 National Guard troops to police the streets of Atlanta.

To allies, Tortuguita’s killing was the climax of an escalation of police and legal tactics meant to stifle the wide-ranging movement to stop construction of the training center, which includes parks advocates, prison abolitionists, and area neighborhood associations. Over the course of December and January, 19 opponents of the police training center have been charged with felonies under Georgia’s rarely used 2017 domestic terrorism law. But Grist’s review of 20 arrest warrants shows that none of those arrested and slapped with terrorism charges are accused of seriously injuring anyone. Nine are alleged to have committed no specific illegal actions beyond misdemeanor trespassing. Instead, their mere association with a group committed to defending the forest appears to be the foundation for declaring them terrorists. Officials have underlined that an investigation is ongoing, and charges could yet be added or removed.

Lauren Regan, an attorney who is the executive director of the Civil Liberties Defense Center, which will represent some defendants, said the charges are legally flimsy and designed to scare movement supporters.

“It’s so next time a vigil happens, mom or the school teacher or the nurse — or someone that has higher risk of randomly getting arrested — is probably going to think twice about going,” she said.

“They’re going to use this to continually vilify and criminalize the wider movement,” added Franklin.

Georgia’s terror law passed in response to high-profile mass shootings including the 2015 massacre of nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, by white supremacist Dylann Roof. The 2017 law expanded the definition of “domestic terrorism” from its original designation as an act intended to kill or injure at least 10 people to one encompassing a range of property crimes. Critics at the time, including the Georgia chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, argued that the law was bound to be used against protesters and to stifle free speech. The charges validate civil liberties’ groups concerns and offer a warning signal for lawmakers in both major parties who have repeatedly proposed federal domestic terrorism legislation as a solution to America’s epidemic of mass murder.

Atlanta Police Department spokesperson John Chafee, on the other hand, defended the use of the law in this case. “We are hopeful the law and the possibility of being charged with this felony will be a deterrent from engaging in criminal behavior,” he told Grist. “We support the right to protest and we will work to ensure those engaged in a lawful protest are able to do so safely.”

Elsewhere in the woods on the day of the shooting, officers tore down 25 campsites and arrested seven activists. Law enforcement also netted bystanders: One Dekalb County Police Department incident report describes two individuals walking along a river trail “in an area that is being occupied by suspects wanted for domestic terrorism.” The Georgia Bureau of Investigation recommended they be “placed in flex handcuffs and transported to the nearby command post.” Later, they were determined to be “vagrants from the city of New Orleans” and were released.

Timothy Murphy was one of the last forest defenders standing. In the predawn hours of January 19, S.W.A.T. team members shone spotlights on Murphy as the activist perched above a treehouse, according to an incident report. Around sunrise, Murphy rappelled down the tree. Dekalb County Police S.W.A.T. members grabbed their legs, cut their harness, and booked them on charges of domestic terrorism.

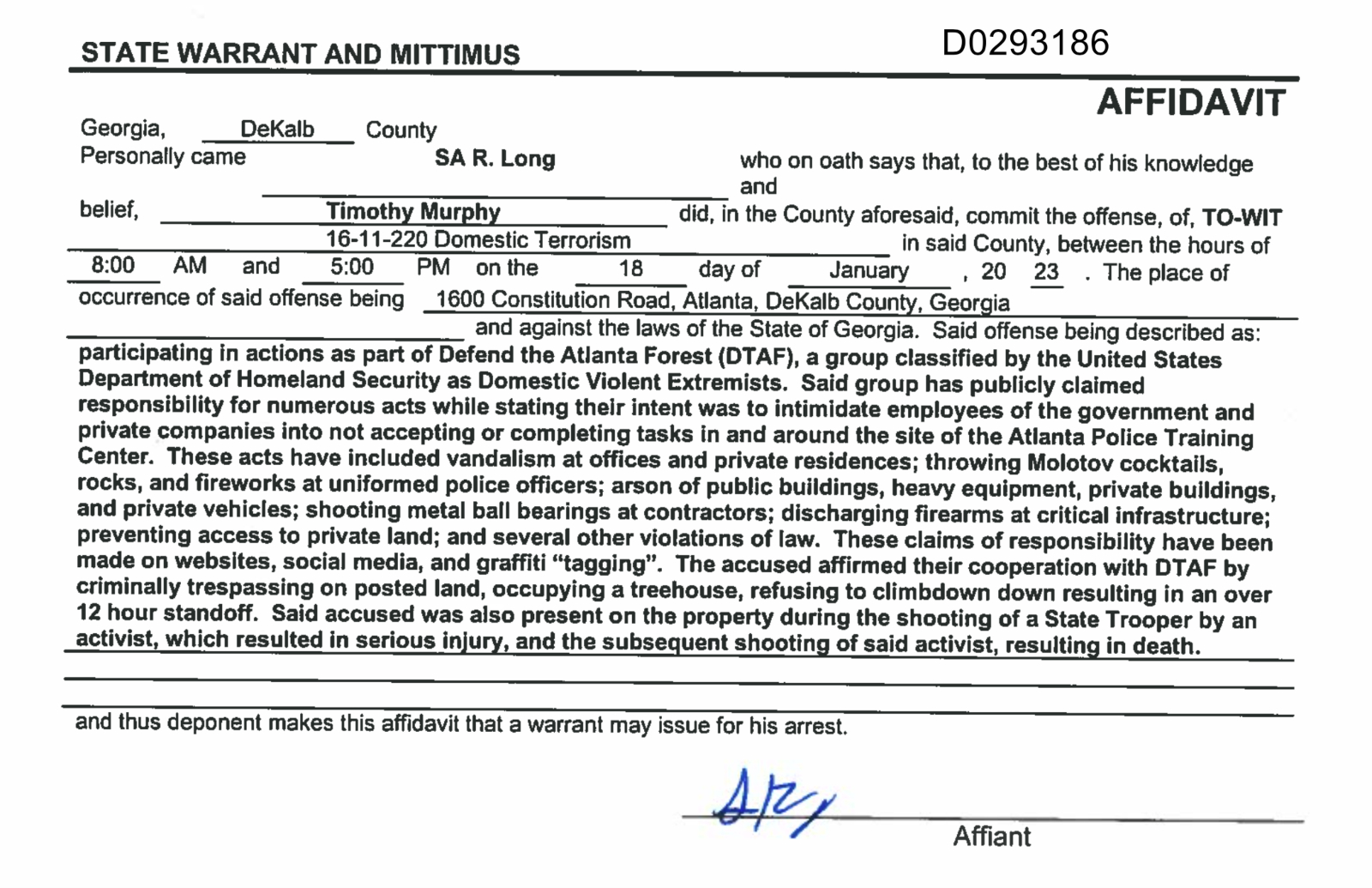

So far police don’t claim that Murphy committed any act of violence or even property destruction. Key to Murphy’s terror charge, according to their arrest warrant, is that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, or DHS, designated a group called Defend the Atlanta Forest as “Domestic Violent Extremists.” In other words, Murphy appears to have been charged with terrorism on the basis of their affiliation with the forest defenders.

In response to questions from Grist, a DHS spokesperson denied that the federal agency classifies any specific groups with this term, while also saying that it does use the term to refer to any U.S. individual or group “who seeks to further social or political goals, wholly or in part, through unlawful acts of force or violence” and regularly shares information about threats with state and local agencies.

Regardless, the Georgia Bureau of Investigation decided that Murphy was a member of the “extremist” group on the basis of the activist’s actions: They trespassed and then refused police orders to leave the treehouse for 12 hours. As a result, if prosecutors move forward with the terror charge, Murphy will face a mandatory minimum sentence of five to 35 years in prison for what’s known as a tree sit — a common tactic among environmentalists.

The Atlanta forest defenders’ warrants state that Defend the Atlanta Forest earned its Domestic Violent Extremist label because members had thrown Molotov cocktails, rocks, and fireworks at police, and also shot metal ball bearings at contractors. They had also committed various acts of property destruction, including vandalism, discharging firearms at “critical infrastructure,” and committing arson of “public buildings, heavy equipment, private buildings, and private vehicles.”

However, besides three allegations of rock-throwing, the 14 forest defenders’ warrants do not appear to accuse them of committing any of the above acts that led to the designation. Grist’s analysis of arrest warrants found that, for nine forest defenders detained during police operations in December and January, their alleged acts of “domestic terrorism” consist solely of trespassing in the woods and camping or occupying a tree house.

A warrant following a police raid on December 13, for example, justifies a domestic terrorism charge by stating that the activist “affirmed their cooperation with [Defend the Atlanta Forest] by occupying a tree house while wearing a gas mask and camouflage clothing.” Another defendant, arrested January 18, told police that they were aware of the Cop City controversy before coming to Atlanta and had planned in advance to sleep on the land — an admission that apparently became the basis for a domestic terrorism charge. “Said defendant admitted to participating in previous protests in other states for environmental causes,” the warrant added.

Four forest defenders charged with domestic terrorism are also accused of possessing incendiary devices or firearms or throwing rocks at fire department and emergency workers and damaging a police vehicle. One of those was charged separately with injuring an officer, who scraped and cut his knee and elbow as the defendant fled. A fifth defendant is separately accused of trying to cut the rope of an arborist attempting to remove them from a tree house.

Six people charged with domestic terrorism during a night of protest in response to Tortuguita’s killing on January 21, including one who was also charged in the woods, face a slightly different set of allegations. Their domestic terrorism arrest affidavits point to felony charges they face for allegedly damaging a nearby Atlanta Police Foundation building and setting fire to a police car. A separate set of arrest citations is ambiguous as to whether the defendants are known to have personally carried out property damage, though one defendant is charged with carrying spray paint, a hammer, torch fuel, and a lighter as well as kicking and spitting on an officer as they were arrested.

The initial arrest citations for domestic terrorism also state that members of the crowd “used explosives/fireworks toward police,” without indicating whether the defendants did so themselves. The street protesters’ domestic terrorism arrest affidavits state that the alleged felonies were carried out with the intention of intimidating officials into changing government policy.

All but one of the activists arrested in the forest were released on bonds ranging from $6,000 to $13,500. None of the street protesters have been released, with four dubbed flight risks and denied bond, and two unable to pay a $355,000 bond.

The forest defenders’ charges appear to stand on shaky legal ground. To be convicted under Georgia’s terror law, an individual must first commit or attempt a felony. Nine of those arrested in the forest are charged with criminal trespass, which is only a misdemeanor.

Also, the acts must be intended to intimidate people, use intimidation to influence government policy, or impact the government through the use of “destructive devices, assassination, or kidnapping.” How trespassing and camping could constitute intimidation is unclear. The law does not contain language about whether associating with a “Domestic Violent Extremist” group counts as terrorism.

Even if the charges are dismissed on the grounds that they do not fulfill the requirements of the law, they may leave a lasting legacy. “One of the problems with state repression is the crackdown and the arrests and the jailing and the bond — for the humans that are targeted, even if they end up being acquitted, all of that takes a toll,” said Regan, the attorney.

Although multiple environmental activists have been prosecuted under federal terrorism law in recent years, it’s been over a decade since the U.S. has seen anti-terrorism charges aimed at a broad swath of environmental activists. During a period known as the “Green Scare” in the mid-2000s, more than a dozen people associated with the Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front were arrested as part of an FBI domestic terror operation. At the time, “eco-terrorism” became the Justice Department’s top domestic terrorism priority, despite the fact that those arrested had made a point to avoid causing any bodily harm even as they burned down facilities they considered environmentally destructive.

The smaller-scale green scare that police have carried out in Atlanta in recent weeks is in some ways even more indiscriminate, since many of the alleged terrorists are not even accused of property damage.

*Update: This article has been updated to clarify that experts Grist consulted considered Tortuguita the only known environmentalist land defender killed by U.S. law enforcement in the modern era. It has also been updated clarify that just one U.S. person was included on Global Witness’ list of land defenders killed since 2012.