This article was produced in partnership with Type Investigations, where Adam Federman is a reporting fellow.

On the morning of March 5, 2012, Debra White Plume received an urgent phone call. A convoy of large trucks transporting pipeline servicing equipment was attempting to cross the Pine Ridge Reservation near the town of Wanblee, South Dakota. White Plume, a prominent Lakota activist, immediately dropped what she was doing and headed to the site, where, within a few hours, a group of about 75 people from the Pine Ridge Reservation gathered.

More than a dozen cars formed a blockade along one of the roads that runs through the reservation. Plume and other activists were outspoken critics of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, part of a larger network carrying oil from the tar sands of northern Alberta, Canada, to refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast. Many Indigenous nations in South Dakota, whose land the convoy was attempting to pass through on its way to the Canadian tar sands, fiercely objected to the project.

“We have resolutions opposing the whole entity of the tar sands oil mine and the Keystone XL pipeline,” White Plume declared after arriving at the site where the trucks had been stopped. “They need to turn around and go back. … They are not coming through here.” But the trucks were so big and unwieldy that the drivers said it would be dangerous, if not impossible, to turn them around.

The standoff in Wanblee was a relatively small protest compared to subsequent actions against the Keystone XL pipeline, which drew tens of thousands into the streets of Washington, D.C., and garnered national attention. Police arrested five activists, including White Plume (who died in 2020) and her husband, Alex White Plume Sr., on charges of disorderly conduct, and released them later that day. Beyond a few stories in Indigenous news outlets and regional papers, the protest hardly registered. Though tribes and landowners in the region had begun organizing around Keystone XL in 2011 and 2012, the pipeline had not yet become the galvanizing force for one of the largest campaigns in the history of the modern environmental movement.

But the events in Wanblee did capture the attention of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which began tracking Native groups campaigning against the pipeline in early 2012. According to documents obtained by Grist and Type Investigations through a Freedom of Information Act request, the FBI’s Minneapolis office opened a counterterrorism assessment in February 2012, focusing on actions in South Dakota, that continued for at least a year and may have led to the opening of additional investigations. These documents reveal that the FBI was monitoring activists involved in the Keystone XL campaign about a year earlier than previously known.

Their contents suggest that, long before the Keystone and Dakota Access pipelines became national flashpoints, the federal government was already developing a sweeping law enforcement strategy to counter any acts of civil disobedience aimed at preventing fossil fuel extraction. And young, Native activists were among its first targets.

“The threat emerging … is evolving into one based on opposition to energy exploration related to any extractions from the earth, rather than merely targeting one project and/or one company,” the FBI noted in its description of the Wanblee blockade.

The 15-page file, which is heavily redacted, also describes Native American groups as a potentially dangerous threat and likens them to “environmental extremists” whose actions, according to the FBI, could lead to violence. The FBI acknowledged that Native American groups were engaging in constitutionally protected activity, including attending public hearings, but emphasized that this sort of civic participation might spawn criminal activity.

To back up its claims, the FBI cited a 2011 State Department hearing on the pipeline in Pierre, South Dakota, attended by a small group of Native activists. The FBI said the individuals were dressed in camouflage and had covered their faces with red bandanas, “train robber style.” According to the report, they were also carrying walking sticks and shaking sage, claiming to be “Wounded Knee Security of/for Mother Earth.”

“The Bureau is uncertain how the NA group(s) will act initially or subsequently if the project is approved,” the agency wrote.

The FBI also singled out the “Native Youth Movement,” which it described as a mix between a “radical militia and a survivalist group.” In doing so, it appeared to conflate a specific activist group originally founded in Canada in the 1990s with the broader array of young Native activists who opposed the pipeline decades later. Young activists would play an important role in the Keystone XL campaign and later on during protests against the Dakota Access pipeline at Standing Rock, but the movement had little in common with militias or survivalists, terms typically used to describe far-right groups or those seeking to disengage from society.

The FBI declined to respond to questions for this story. In an emailed statement, a spokesperson for the Minneapolis field office said the agency does not typically comment on FOIA releases and “lets the information contained in the files speak for itself.”

The FBI was not the only federal agency keeping tabs on Keystone XL pipeline protesters in the early years of the anti-pipeline movement. According to additional records obtained by Grist and Type Investigations, an obscure intelligence division within the U.S. State Department, which had jurisdiction over the pipeline because it crossed an international boundary, collected hundreds of pages of records on Keystone activists, landing one of them in jail on charges of trespassing (which were eventually dropped). Working in tandem with the FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force, the State Department created an email account to “track all Keystone XL protest incidents” and monitored events in cities across the country, including in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Houston, and Honolulu. The task force even highlighted candlelight vigils held in several major cities in 2014, describing one group of protesters as “peaceful, holding candles and signs.” These records reveal for the first time that the State Department was also involved in monitoring activists from late 2013 through the Obama administration’s decision to reject the pipeline in November 2015, though the case file wasn’t officially closed until November 2016.

The State Department was especially interested in the work of environmental groups D.C. Action Lab and 350.org, as well as the “pledge of resistance,” organized by groups including CREDO, a mobile phone company that supports progressive causes, which called for activists to engage in civil disobedience to stop President Barack Obama from approving the Keystone XL pipeline. By late 2015, tens of thousands of people had signed the pledge and environmental groups held direct action trainings in dozens of cities. Meanwhile, the Department of Homeland Security and state and local law enforcement agencies along the proposed pipeline route, according to previous reporting in The Guardian and other news outlets, were also intimately involved in investigating these activities, creating an unprecedented domestic surveillance network that is only now fully coming into focus.

In a written response, a State Department official said the purpose of tracking Keystone XL protesters was to “provide law enforcement with situational awareness of activities that could impact the security of State Department personnel, facilities, or activities.”

The department said it takes any potential threats against its personnel in the United States seriously but declined to comment on whether Keystone XL pipeline protesters had engaged in such behavior. In addition, the department declined to comment on why it singled out specific groups such as D.C. Action Lab and 350.org, as well as the CREDO campaign. The department said it is committed to upholding freedom of speech and assembly, “while also maintaining our security responsibility of protecting our facilities and U.S. personnel from those who may violate applicable laws.”

Environmental activists and attorneys who reviewed the new documents told Grist and Type Investigations that law enforcement’s approach to the Keystone XL campaign looked like a template for the increasingly militarized response to subsequent environmental and social justice campaigns — from efforts to block the Dakota Access pipeline at Standing Rock to the ongoing protests against the police training center dubbed “Cop City” in Atlanta, Georgia, which would require razing at least 85 acres of urban forest.

The FBI’s working thesis, outlined in the new documents, that “most environmental extremist groups” have historically moved from peaceful protest to violence has served as the basis for subsequent investigations. “It’s astonishing to me how such a broad concept basically paints every activist and protester as a future terrorist,” said Mike German, a former FBI special agent who is now a fellow at the nonprofit Brennan Center for Justice.

Sabrina King, an organizer with the conservation group Dakota Rural Action from 2012 to 2016, who went on to work for the ACLU in South Dakota, North Dakota, and Wyoming, spent nearly a month at Standing Rock. She believes the FBI’s characterization of the activist community — and Native youth in particular — as potential extremists helped set the stage for the increasingly aggressive government actions, including the use of FBI informants and heavily armed state and local police departments, directed at environmental protesters around the country in later years, from Standing Rock to the Line 3 pipeline in Minnesota.

“This is the direct line to Standing Rock,” said King, who reviewed the newly obtained FBI documents. “None of that just happened. These law enforcement agencies had literally been training for [years] for Keystone, but then they used it on Dakota Access.”

In the years after the Wanblee blockade, the campaign opposing Keystone XL gained broad public appeal. It tapped into both local concerns over damage to land and water and also a rapidly growing national movement to end fossil fuel extraction altogether. It minted a multigenerational coalition of activists, many of whom had not been previously engaged in environmental politics.

The campaign also openly embraced nonviolent direct action, which marked a new chapter for some environmental organizations. In 2013, for example, the Sierra Club broke its long-standing prohibition on members engaging in civil disobedience — earning it a mention in the newly obtained FBI files. That year, activists, including the Sierra Club’s then-executive-director Michael Brune, used zip ties to attach themselves to the White House fence, resulting in mass arrests. The campaign included mainstream liberals who supported Obama and felt he could be persuaded to block the pipeline, as well as veterans of the environmental movement who had long been willing to engage in confrontational direct action.

This alliance posed an unexpected threat to companies involved in fossil fuel extraction, including TransCanada, the company behind the pipeline, and set off alarms within the federal government. Hundreds of pages of FBI and State Department files released through the Freedom of Information Act over the last decade highlight an increasingly close relationship between law enforcement agencies and the fossil fuel industry. The newly obtained documents show that, as early as 2012, the FBI was describing TransCanada, a multinational corporation headquartered in Calgary, Canada, as a “domain stakeholder” with direct access to the White House.

“Resistance to the Keystone XL pipeline was really the first pipeline campaign that I recall that there was organization on both sides of the fight,” said Lauren Regan, executive director of the nonprofit Civil Liberties Defense Center, which provided legal support to dozens of activists arrested during the campaign. “As we were collecting public records documents, organizers were shocked at how much running time TransCanada had with state and federal governments before any of them sensed that something was happening.”

Previously reported documents show that, less than two months after the FBI opened its investigation into Native activists, the agency held a “strategy meeting” with TransCanada and industry partners in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, an hour away from Cushing, where many of the nation’s major pipelines converge. (In 2012, Obama delivered a campaign speech in Cushing announcing that he would fast-track the southern leg of the Keystone XL pipeline.) Representatives from the Department of Homeland Security, the National Guard, and state and local police departments were also present. Indeed, the author of the February 2012 FBI file from the bureau’s Minneapolis field office noted that they would be attending the “regional working group meeting” to “ensure coordination and resource management between bureau field offices affected and the domain stakeholder, TransCanada Corporation.”

By the end of 2012, the FBI’s Houston field office also began collecting information for a domestic terrorism assessment that focused on Tar Sands Blockade, a scrappy coalition committed to nonviolent direct action, which had been at the center of the campaign to block construction of the pipeline in Texas. In one of their most prominent actions, Tar Sands Blockade had teamed up with a private landowner and set up tree-sits in the pathway of the pipeline. The FBI closely tracked protest activity among members of the group, one of whom later ended up being placed on a U.S. government watchlist for domestic flights, and cultivated at least one informant, according to files obtained in 2015 and previously reported in The Guardian. The investigation was initially opened without prior approval from the chief division counsel and the special agent in charge, in violation of FBI rules pertaining to “sensitive investigative matters” involving the activities of political organizations.

Meanwhile, starting in late 2012, TransCanada began delivering its own briefing to local law enforcement agencies along the proposed pipeline route. The PowerPoint presentations, which included profiles of organizers at 350.org, Rainforest Action Network, and Tar Sands Blockade, encouraged law enforcement to pursue federal anti-terrorism charges in conjunction with the FBI.

At the same time, tribes and landowners in South Dakota were busy raising awareness about the pipeline and the threats it posed to groundwater and Indigenous treaty rights. In September 2011, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, along with First Nation Chiefs of Canada, held an “emergency summit” in South Dakota, after which they issued the Mother Earth Accord, also referenced in the new FBI files. The agreement, signed by most tribes in the state, called for a moratorium on tar sands development and an end to the shipping of equipment for the pipeline through the United States and Canada.

The blockade in Wanblee was one of several actions the FBI cited to support its conclusion that the movement could potentially turn to violence. The counterterrorism assessment documents other public meetings, including a protest held by the Oglala Lakota Nation in early February 2012, that the FBI acknowledged was “protected First Amendment activity.” The FBI warned that, after Wanblee, any commercial vehicles associated with the pipeline could now be held “hostage” by Native Americans “who oppose the exploration, extraction, refinement, and/or distribution of petroleum-based products.” The FBI file included the names of those arrested and noted that South Dakota’s U.S. attorney had considered prosecuting the activists under the Hobbs Act, a 1946 law designed to prevent racketeering in interstate commerce, typically through robbery or extortion. Violating the act can carry a punishment of up to 20 years in prison.

Along with monitoring protest activity, the agency was particularly concerned with the activities of Native youth. Certainly, Native youth played an important role in the Keystone XL campaign, and later in organizing opposition to the Dakota Access pipeline. But their actions hardly seemed like the work of a radical militia. In 2015, members of the Lakota Nation’s Cheyenne River Sioux tribe formed the One Mind Youth Movement, a kind of mutual aid society for teens struggling with suicide and depression. Eventually they turned their attention to the Keystone XL campaign and began networking with activists in other parts of the country and around the world. At Standing Rock, members of One Mind formed the International Indigenous Youth Council, which was known for its efforts to defuse tensions between law enforcement and protesters, even drawing criticism from some activists who felt they were too conciliatory.

The FBI saw things differently. According to the newly obtained files, the Minneapolis office appears to have opened another inquiry into what it described as the “Native Youth Movement” to “marshal information about extremist groups in Indian Country targeting a myriad of issues, to include threats to the proposed Keystone XL pipeline.” Those records may never be released, however. The FBI denied a Freedom of Information Act request for the material, and asserted that releasing the “investigative file” would reveal intelligence sources and methods or law enforcement techniques and procedures. In October, the Department of Justice rejected an appeal filed by Grist and Type Investigations, stating that “disclosure of the information withheld would harm the interests protected by these exemptions.”

Shortly after Obama and the State Department rejected the Keystone XL pipeline in 2015, Paula Antoine, the director of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Sicangu Oyate Land Office, headed north to the Standing Rock reservation to meet with elders interested in establishing a prayer camp on the banks of the Missouri River. During the fight over Keystone XL, Antoine had helped to set up the first “spirit camp” near the community of Ideal, South Dakota, where she was raised. The idea caught on. Lewis Grassrope, a member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribal Council, set up a camp on land belonging to his mother a few miles from the Missouri River. A third camp was erected on the Cheyenne Sioux Reservation. Each served as a gathering place for organizers and activists involved in the Keystone XL campaign. Now, activists spearheading the campaign to block the Dakota Access pipeline wanted to do the same thing.

“To me it [KXL] was like the precursor to No DAPL,” Grassrope said, referring to the campaign to block the Dakota Access pipeline. “We knew that the fight was coming, we just didn’t know when.”

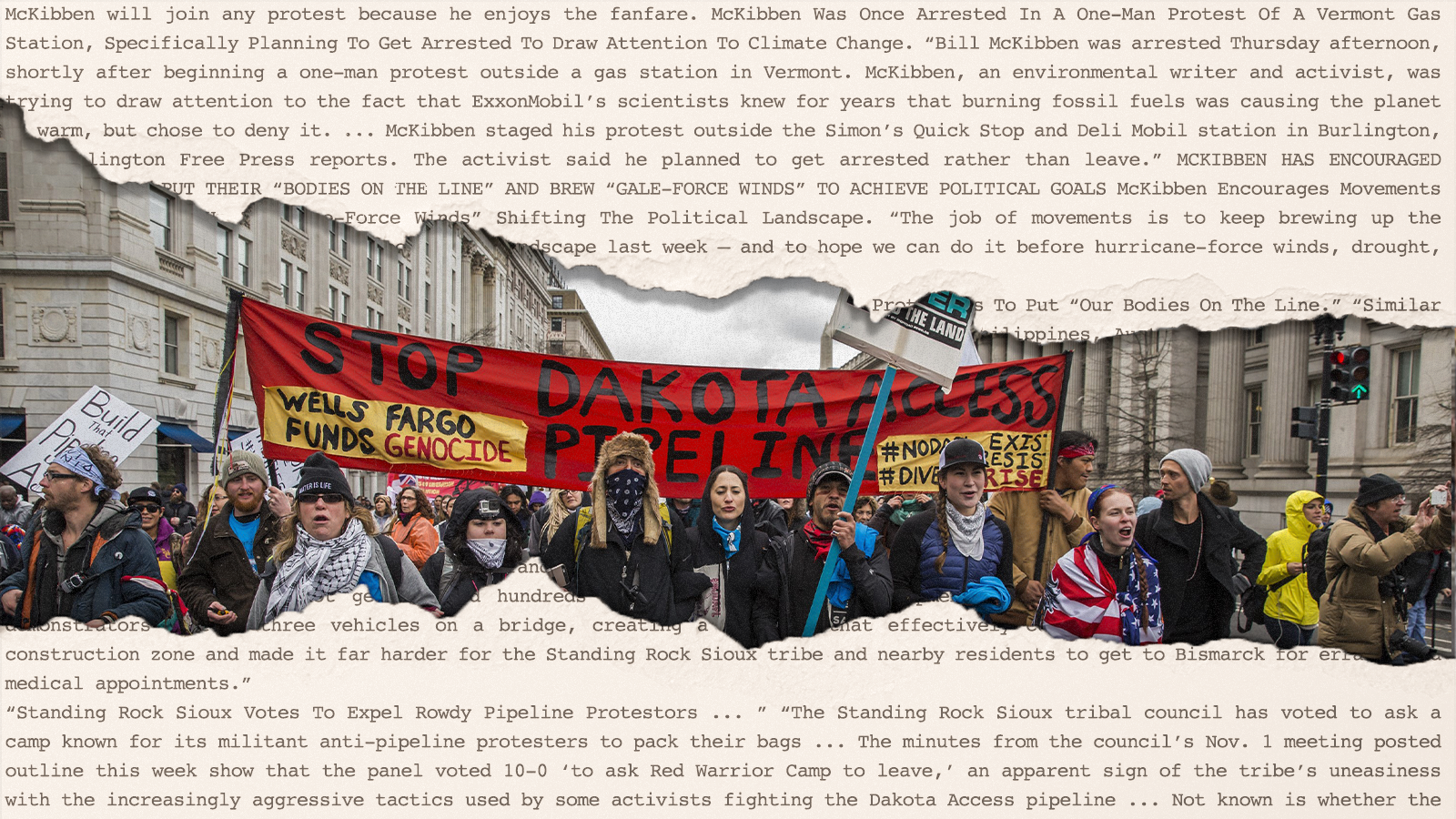

The spirit camp at Standing Rock started out small and was maintained by a group of local activists and their allies. But by the fall of 2016, it had become the focal point of the growing movement to block the pipeline. Thousands of people taking on the mantle of “water protectors” eventually descended on the region. Standing Rock would capture the world’s attention.

But as the newly obtained files show, after years of tracking Keystone XL protesters, the fossil fuel industry and law enforcement had prepared for this moment. Energy Transfer Partners, the company building the pipeline, hired a private security firm that monitored activist groups and produced dozens of intelligence reports, which were later leaked and reported by The Intercept. This information was shared with law enforcement and the FBI, blurring the lines between public and private partnerships, with the fossil fuel industry at the center. The security firm, TigerSwan, collected intelligence on activists and used an ex-Marine to infiltrate anti-pipeline actions. At the same time, a Department of Homeland Security-funded fusion center in North Dakota developed a “links chart” to map out the leadership of the movement, focusing almost exclusively on Native American activists.

“We all had people following us,” said Antoine. “They knew who we were.”

As the encampment grew, the National Guard was eventually enlisted in what became one of the largest police and military deployments in North Dakota’s history, according to historian Nick Estes’s Our History is the Future, his book about the pipeline fight. “Cops in riot gear conducted tipi-by-tipi raids … They dragged half-naked elders from ceremonial sweat lodges, tasered a man in the face, doused people with CS gas and tear gas, and blasted adults and youth with deafening LRAD sound cannons,” Estes writes. Law enforcement also appeared to undermine parts of the movement from the inside. Red Fawn Fallis, a Lakota activist, was sentenced to a nearly five-year prison term for possession of a handgun, following a skirmish with police at Standing Rock. According to reporting by Will Parish in The Intercept, she had been involved in a romantic relationship with an FBI informant. It was later revealed that the weapon belonged to him.

Even after the camps at Standing Rock had been broken down and the last protesters had gone home, the surveillance continued. Grassrope, now 46, returned to the spirit camp he’d established on the Lower Brule reservation and, along with a handful of others, lived in tipis, yurts, and military tents. One day, the FBI called and said they wanted to inspect the camp. “They were pinpointing certain camps created after Standing Rock,” Grassrope said, which they believed were preparing to turn their attention, once again, to the Keystone XL pipeline, which then-President Donald Trump had revived.

Lauren Regan of the Civil Liberties Defense Center said that the fossil fuel industry and law enforcement agencies have continued to strengthen their partnership. In particular, the oil and gas industry’s information-sharing networks have become more sophisticated. In some cases, corporations have made direct payments to state and local law enforcement. For example, Enbridge, a Canadian multinational that recently upgraded its Line 3 pipeline, which cuts through tribal land in Minnesota, reimbursed state and local law enforcement to the tune of more than $8.5 million for their work policing protests against the pipeline.

More broadly, using the playbook that TransCanada developed, the industry has continued to push lawmakers to pursue enhanced felony charges for pipeline protesters. Lawmakers in nearly 20 states have passed legislation criminalizing actions that target “critical infrastructure.”

“It was definitely part of the state and law enforcement strategy to escalate repression to the point people wouldn’t want to continue taking action,” said Ethan Nuss, a senior campaigner at Rainforest Action Network who was involved in protests targeting the Keystone XL pipeline and Line 3.

Since the Keystone and Dakota Access pipeline fights, the law enforcement response to the environmental movement, and mass protest in general, has remained severe. In January 2023, six Georgia state troopers shot and killed Manuel Esteban Paez Terán, a 26-year-old medic involved in protests around the building of the police training center in Atlanta known to activists as Cop City. An autopsy requested by the family revealed that Tortuguita, as Terán was known, was likely sitting on the ground with both arms raised when they were killed, and an autopsy by DeKalb County found that they had been shot at least 57 times — the first time an environmental activist has been shot and killed by police on U.S. soil. Meanwhile, the state has charged dozens of protesters in Atlanta with domestic terrorism. And according to reporting by Grist and Type Investigations, the FBI has been tracking disparate groups involved in the campaign, some as far away as Chicago.

Despite this crackdown, however, actions targeting fossil fuel infrastructure continue to pop up across the country. In October, police in Virginia arrested three activists and charged them with trespassing and obstruction after they attached themselves to equipment used in building the last leg of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Fast-tracked as part of negotiations over the Inflation Reduction Act, the 303-mile pipeline stands to release up to 40 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent into the atmosphere every year once it is completed, according to its environmental impact statement. The developer has since sued two of the protesters, citing congressional approval of the project and arguing that the action caused “substantial delays and expenses” for the company.

“With the global warming crisis at its height, these fights are going to happen more regularly,” said Grassrope. “We have to move faster. That is what it comes down to.”

For the activist community, the Keystone XL campaign still serves as a source of inspiration. When the project was officially terminated in June 2021, Paula Antoine took her granddaughter out to the spirit camp on the Rosebud Sioux reservation. She made an offering and prayed, as she had many times before, for the continued protection of the land.