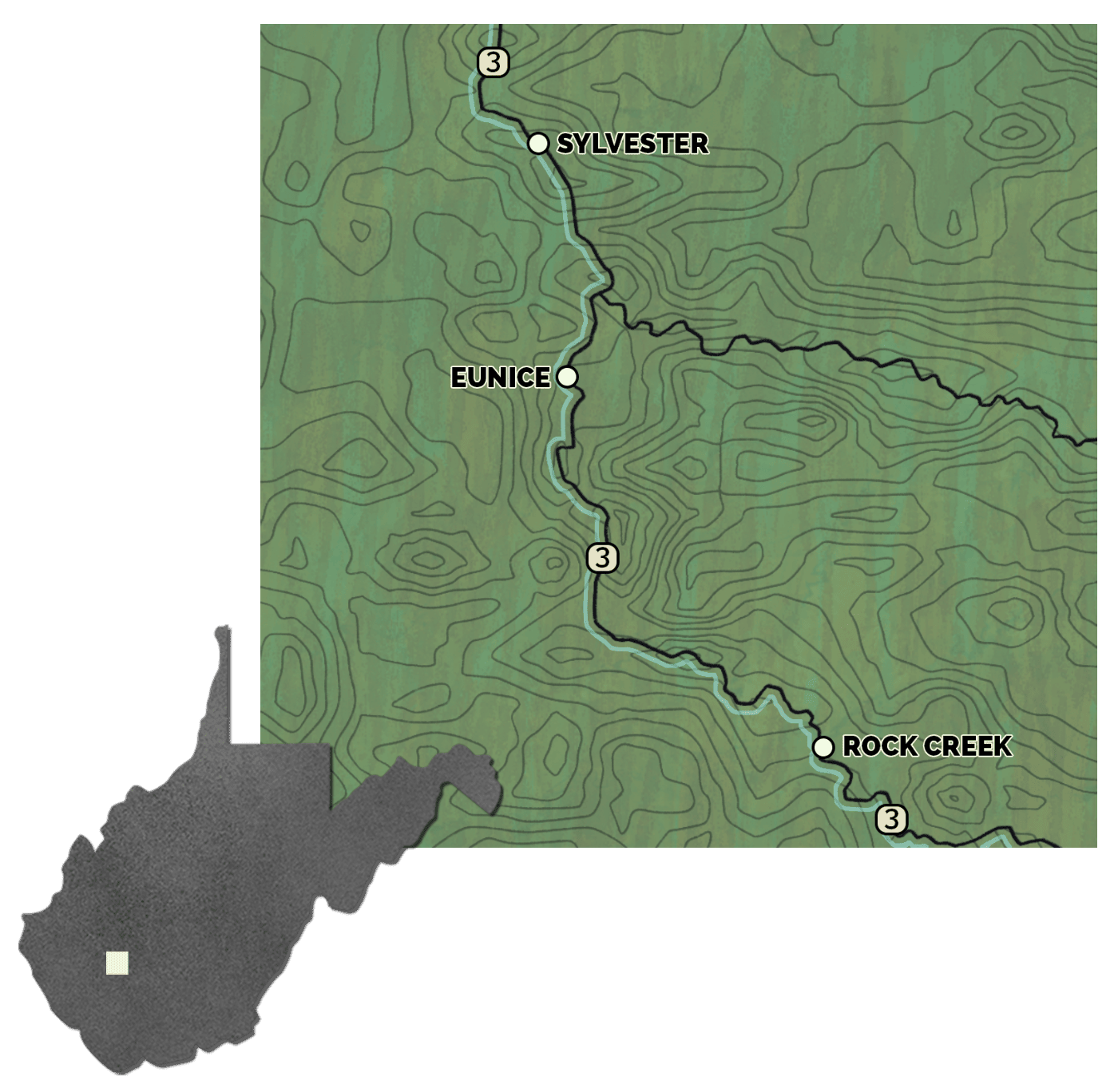

When you come down around the bend in the road that runs along the Coal River, a pickup riding your tail because you’re not inclined to take hairpin turns at 60 miles an hour, you’ll arrive at the house where Junior Walk grew up, where his parents still reside. Eunice, West Virginia, is not much more than a row of bungalows that sit with their backs right up against the road and their front doors maybe a hundred feet from the freezing-cold Coal River. Walk’s sister Natasha and her partner and baby live in the same stretch of homes, and he himself owns a house two doors down. But his roof is falling in and the cost to fix it is more than the house itself is worth, so he’s “giving it back to nature.” There are three junk cars in his yard pending sale to John at the gun and pawn shop in the next town over, once a suitable price is agreed upon.

Walk leads the way past his parents’ house, a shaggy behemoth of a dog barking gruffly in the yard. (“He’s half wolf,” he explains. “My sister’s ex-boyfriend paid thousands of dollars for him.”) On through a grove of trees, branches still bare in early spring, thick with bramble bushes. The air is damp with light rain spitting from a sudden cloud, but grainy in a way that you can feel in the back of your throat. From the muddy riverbank you can see an enormous chute protruding from one of the mountainsides that frames the valley, black coal pouring out of it to be carted off by a constant parade of trucks. Clouds of taupe dust billow off the trucks as they pull in and out of the mine entrance, and swirl in eddies over the ragged asphalt.

Not much more than the length of a city block stretches between the coal chute and the Walks’ front door. Coal has been mined in the valley for the past two hundred-odd years — and the Walks and their kin have been here almost as long. But the Black Eagle mine is new, having opened in 2018, and a stream of anthracite, dust, and rock pours out of the mountain and more or less directly onto the front doorstep. Walk’s grandfather already has black lung from years spent working in another mine up the road; his mother Shelia wakes up and wipes a layer of silica dust that collects on the kitchen counters overnight, even with every window shut. Natasha’s baby was born premature.

Walk is 32 years old and has been fighting against coal companies in the valley his entire adult life. There was a time when he was traveling around to every state in the lower 48 (by his own count) to speak on behalf of Coal River Mountain Watch, the tiny grassroots organization where he works. He would go to summits and conferences and university halls and talk about mountaintop removal mining and contaminated creeks and poisonous air and sky-high rates of cancer, and the power of real, on-the-ground, flesh-and-blood activism to fight back against all that.

But today, if you suggest that Walk is a homegrown hero of the “youth climate movement,” he bristles. For two reasons: One, he’s been paying his own bills for half his life, which he’d argue places him squarely outside of the “youth” category. And two, he’s tired of being lauded as a savior in the war on coal, especially because he’s seen the way that war goes when the environmental movement’s attention turns elsewhere.

At the start of this millennium, the Coal River Valley that runs through southern West Virginia’s Boone and Raleigh counties was the site of a vibrant anti-coal movement. A few ambitious and adventurous environmental activists decided that if they wanted to put a sword in the heart of the looming climate crisis, there was no better place to start than deep inside the dragon’s lair.

The legend pretty much writes itself. Coal companies were tearing down biodiverse forests and blowing up mountains to excavate many millions of tons of climate-warming black gold, leaving impoverished and sickened communities and destroyed ecosystems in their wake. To fight back against them, hundreds of activists traveled from all over the world to West Virginia, forming blockades, camping out in trees, and chaining themselves to equipment.

And somewhere along the way, the movement lost its momentum. Over the course of a decade, the spotlight on West Virginia’s coal country faded, even as new surface mines continued to grow like a fungus. A new threat had appeared: fracking, and all the frenzied new fossil fuel development that came with it. The activists slowly packed up and trickled back home or joined protests against oil and gas pipelines. The coal industry remained, its grip weakened by lawsuits, bankruptcies, and the growth of cheap natural gas, but very much alive.

This is an American environmental story for the 21st century, with all the trappings — the fickle attentions of fame and the media, the seemingly never-ending battle between humans and corporations — all tied up in the tale of a man trying to protect his home. The battle against coal expansion and mountaintop mining continues, but without the media attention or the funding that came with it back when the well-known climate scientist James Hansen came to town. But it’s hard for someone like Walk to abandon his fight against the coal company, when the stakes are no less than the home he hopes to live in forever.

To learn how civil disobedience in the name of climate change made its way to Walk’s hometown, I found Mike Roselle, the 68-year-old veteran activist who co-founded the eco-activist collective Earth First! and orchestrated Greenpeace’s first American ventures into organized civil disobedience in the latter half of the 1980s. He organized his way across most of the Mountain West to land in the hollowed-out mining town of Rock Creek, West Virginia, down the road from the Family Dollar and the Exxon and over a clattering wooden bridge, on a plot of land with three cabins tucked between the Coal River and a grove of trees.

Roselle has been fixing up the property himself for about 15 years. He first started working on it when he rented it to house the young anarchists and activists who had migrated up to the valley to join the anti-mountaintop removal cause.

The middle cabin where he and his roommate Cat Dees, another transplant brought here by the movement, reside is humbly decorated, with a wood-burning stove and rows of mason jars lining the kitchen walls. He has grown old here; when I meet him he is tall and thin, with bone-white hair and ice-blue eyes, and he steps slowly and carefully around the cabins to describe the work he’s done: an entire rebuild of this wall of this one, full rewiring, installation of the warm, gold-hued kitchen.

Earth First!, when it got started in the 1980s, operated by the motto “No Compromise in Defense of Mother Earth.” It garnered the attention of environmentalists and loggers alike for protests in which activists locked themselves to trees and logging equipment, occupying forest lands they sought to protect for months at a time. But in 2005, Hurricane Katrina, and all the urgency it portended for climate change, turned Roselle’s attention from forests to coal. He started Climate Ground Zero in Montana, where he struggled to organize direct actions against coal development; he couldn’t get a dozen people to show up to block a coal train. It was in 2005 that he met Julia Bonds, known as Judy, the Goldman Prize-winning founder of Coal River Mountain Watch.

The legend — if you believe Roselle himself, who loves to spin a yarn — is that Bonds caught him and his friends sneaking off into the woods to smoke a joint at a conference for forest conservation activists, they invited her to join them, and the rest is history. That was how Roselle first learned about how all across southern West Virginia, coal companies were using explosives to blow the tops off mountains to lay bare the coal underneath, turning lush forest to surface mines. Over a million acres of forest had been lost, countless biodiverse ecosystems destroyed, any number of streams polluted with the resulting waste and rubble bulldozed into valleys, and, of course, the coal played a key role in pushing carbon emissions to the limits of livable levels. Bonds insisted that it had to be seen to be believed, and invited Roselle to the Coal River Valley that very spring.

“They organized a trip to pick ramps, which I learned was kind of a traditional spring outing for many families, and everybody gets together and has a good time,” he recalled. “So we went up to Cherry Pond Mountain, which was everybody’s favorite gathering spot, and picked ramps. And then Judy says, ‘Well, I hope you like this place because next time you come here, it won’t be here. Massey Energy is committed to blow it up.’”

Bonds wanted him to take the Redwood Summer model pioneered in California by Earth First! leader Judy Barri, and replicate it to block mountaintop removal mining in West Virginia. In June 1990, Barri had organized a training camp for young activists, largely college students, to teach them how to use their bodies to protect the redwood forest in Humboldt County, California. They took part in tree sits, where they’d camp out in the canopy, or chain themselves to the enormous trunks. They would lie spread-eagled on the ground in front of logging equipment and gather en masse to blockade the dock in Eureka, California, where timber would be loaded for export.

Roselle started spending more and more time in Appalachia, collaborating on actions and blockades with the Tennessee-based anti-mountaintop removal organization Mountain Justice. He eventually made Rock Creek the home of Climate Ground Zero in 2008, in large part to support the efforts of Coal River Mountain Watch. That year, Bonds and the rest of the Coal River Mountain Watch cohort learned that Massey Energy had acquired a permit to construct a road up to Coal River Mountain to start mining. The moment had come. Roselle pulled up a few YouTube videos of footage from Redwood Summer, and everyone agreed: We want to do this. They organized a blockade of the road, and then another, and then another.

That was the year Junior Walk turned 18 years old, and his life began to change.

When Walk graduated from high school in 2008, he had been accepted to the Art Institute up in Pittsburgh. He quickly realized that neither he nor his family had any chance of pulling together the tuition money, so he abandoned all college plans and got a job at the Elk Run Coal Processing Plant in Sylvester, another town in the valley, alongside his dad.

Elk Run is notable for two reasons: It was the first non-union mine established by the coal baron A.T. Massey, a cannon fired in the United Mine Workers of America conflict in the 1980s. Supporters of the union set fire to the plant more than once.

It’s also the site of one of three massive coal waste impoundments in the Big Coal River watershed. The liquid slurry left over from treated coal, after it’s processed into its lightest form for shipment, gets poured into a hollow that’s dammed up by the solid waste. These black lakes of toxic sludge, hundreds of feet deep and contained by not much more than a wall of mud and rock, are a looming threat to the communities that lie beneath them, nestled at the foot of the mountain.

Walk performed odd maintenance jobs at Elk Run. One of them entailed wading thigh-deep through the coal waste slurry as it got pumped out into the impoundment. He couldn’t avoid the thought that he might die either from drowning in slurry or chemical exposure-induced cancer, so he quit only to find that there weren’t a whole lot of options: Dairy Queen, Dollar General, and that was about it. Within the year, he’d taken another job working security on a strip mine, where he’d sit for hours every day and watch bulldozers and excavators rip chunks out of the mountain, hungry for the coal beneath.

“Within the first week of me working up there, I just started feeling miserable about it, watching that machinery tear down that mountain,” Walk says, recalling the dust and noise that plagued his own childhood.

Walk had known Judy Bonds his whole life; he went to school with her grandson, and she worked at the gas station with his grandma. After a few weeks on his security job, he went down to the Coal River Mountain Watch office and had a heart-to-heart with Bonds about what he was seeing. Soon after, he started volunteering for Coal River Mountain Watch, writing their newsletter on a clunky desktop computer he’d built himself.

“I would load that into the passenger seat of my car and drive it to work with me, and I’d run an extension cord out to the box on the power pole,” he recalls, gleefully. “And I’d sit there getting paid as a security guard while popping out articles for the Mountain Watch newsletter.”

By the start of 2010, Bonds had given Walk a staff job at Coal River Mountain Watch, where he took on a wide variety of roles to suit a tiny organization with intermittent funding and a fairly daunting mission. That meant scouting sites for blockades and protests, recruiting and training activists, and planning and participating in the actions. He traveled around the country — frequently with Larry Gibson, a prominent local anti-mountaintop removal activist — giving talks at college campuses and environmental conferences: “I would try to convince everybody that I could that it was a good idea to chain themselves to some big yellow piece of equipment.”

At the time, a growing slate of celebrities was making the trek down to the valley. Grammy-award-winning country singer Kathy Mattea, a native of Charleston, the state capital, met with Judy Bonds and marched up Blair Mountain to protest its likely destruction. The actress Daryl Hannah published a rambling op-ed about her experience getting arrested with James Hansen while protesting mountaintop removal around the Coal River. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. narrated a documentary on the subject.

Walk, meanwhile, played a part in recruiting the valley’s cadre of foot soldiers. Members of other groups, like Mountain Justice and Climate Ground Zero, lent a hand in organizing and manpower. The population of the entire Coal River Valley numbers in the low thousands, and at the peak of the movement around 2009 there were a couple hundred activists from out of town who had come to join the cause.

Some culture clash was inevitable. Shelia Walk, Junior’s mother, says that the fact that the Coal River Valley is so secluded makes an influx of anything new and different all the more noticeable: “Anyone that’s coming around with pink hair, everybody’s like — gasp!” Early on in Climate Ground Zero’s tenure in Rock Creek, one organizer’s dog killed a local’s prize fighting chicken.

There were moments of more peaceful integration. In the late 1990s, Gibson had gotten a few dozen acres on top of Kayford Mountain put into a land trust, and he’d built cabins and set up a gathering area where activists could get together to socialize, plan actions, or just enjoy nature. Shelia Walk and a few other women in the community regularly came up to the mountain to cook for them, including for a Fourth of July event well-attended by both locals and activists. John Paul Webber, the 6-foot-5-inch Gadsden-flag-tattooed proprietor of the gun-and-pawn shop in Whitesville, got shit-faced one night and rode his four-wheeler up Kayford. Walk initially thought that Webber had shown up just to wreak havoc, but they hit it off and today are “first-tier” friends.

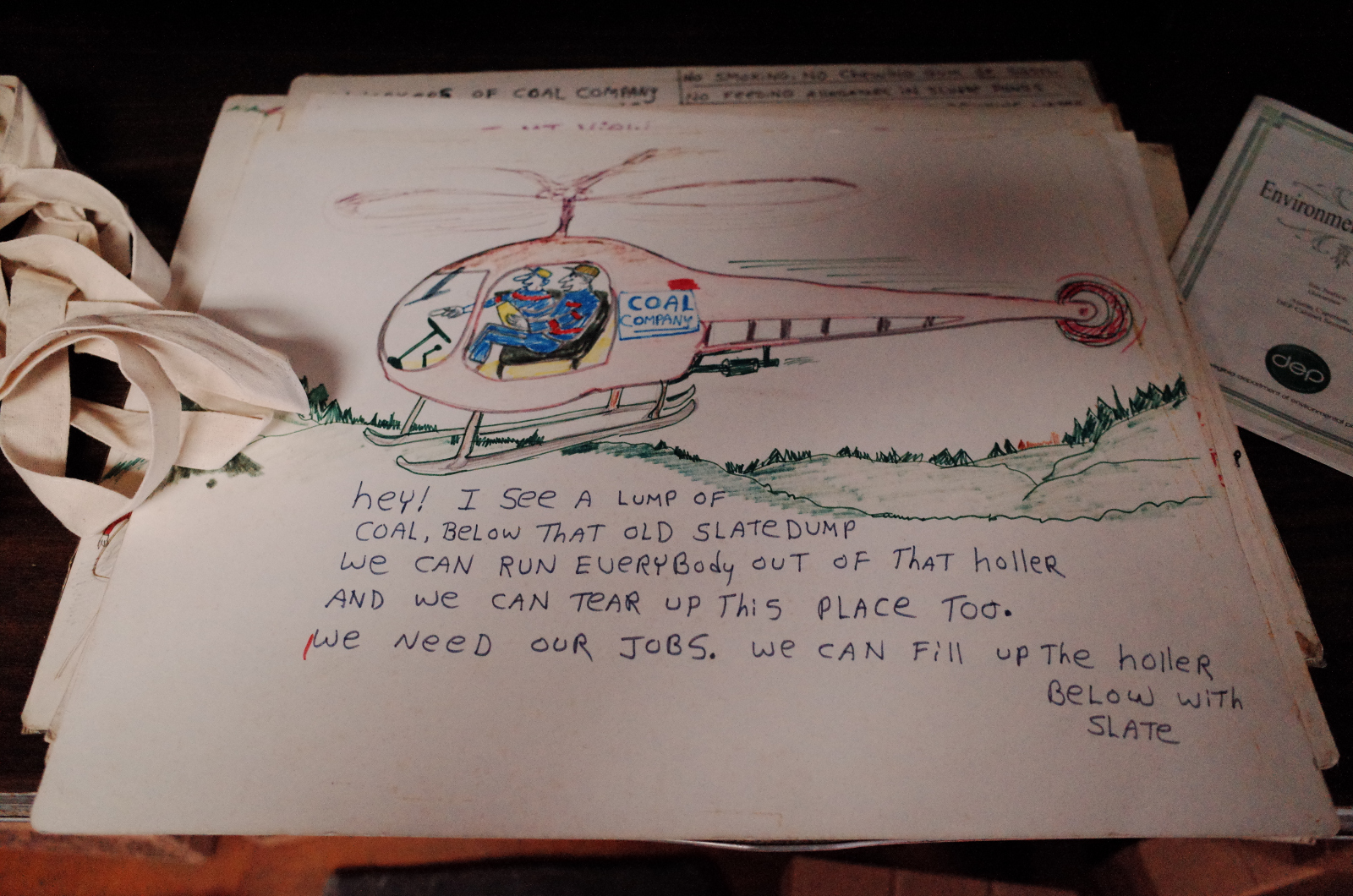

Webber’s was one of the friendlier drunken ambushes of Kayford. Many residents of the Coal River Valley have bought their homes and fed their children thanks to the only real industry within 100 miles, and if you ask them about the anti-mountaintop removal movement you might hear a very different perspective: God put coal in the mountain so we could take it out. The way many locals saw it, the anti-mountaintop-removal movement posed a threat to their livelihoods — a belief eagerly fueled by the coal companies. Early in his activist career, Walk was never seen with his father because of the risk that would pose to his job at the coal processing plant.

The activists’ victories mounted. They demonstrated at then-Governor Joe Manchin’s office and mansion in Charleston as well as in Washington, D.C., securing more and more national attention. They successfully blocked or delayed numerous permits to fill streams with mountaintop removal waste. Activists thwarted blasting on the Bee Tree mine site with the then-longest tree-sit in West Virginia history. In 2010, Coal River Mountain Watch scored a huge coup in a years-long battle to get Marsh Fork Elementary moved outside of the danger zone of the coal silo and the slurry impoundment, and rallied together the money to construct a new school several miles up the road, including a long-disputed donation from Massey Energy. Walk calls this the greatest victory of his activist career.

The coal companies started to pay more attention, and their employees and the families of their employees did too. Sneers in the grocery store grew to hollered threats out of truck windows and worse. Walk has had a gun pulled on him more times than he can count.

Many locals still see the activists as an invasion of outsiders, even though the movement’s leaders were almost entirely born and bred in the valley, describing them as paid by outside organizations to come in to cause trouble. Cliff Lester, a retired coal miner at the Catenary mine who now runs a pay lake stocked with trout and catfish at the south end of the valley, recalled that the activists “made life a living hell” for those who worked in the coal industry at the time.

“I don’t know if they didn’t understand or if they just didn’t really care,” he says. “They just look at it as destroying mountains, but in reality, we took the coal out that was needed for electricity, for building buildings. And over the years, I’ve seen the coal industry go down extremely. We couldn’t get permits. A lot of people lost their homes, lost their jobs, their vehicles, everything.”

Those lost jobs, however, have less to do with the effectiveness of the activists and more to do with the economic realities. The mechanization of coal removal and processing had eliminated the need for thousands of human jobs, and looming competition from cheap natural gas in fueling power plants made coal a less desirable commodity.

But the strength of the anti-mountaintop removal movement in the Coal River Valley was the fact that it was spearheaded by people who had deep roots in the community, who love their home so much that they will be shunned by their own neighbors to defend it. “You get a handful of very committed people, people who something inside of them just snaps one day and they decide, you know, screw it, I’m going to devote my life to being a nemesis to the coal industry,” Walk says. “I mean, that’s what happened to me.”

It also happened to Judy Bonds, whose coal miner father died of black lung, and who then co-founded Coal River Mountain Watch to fight back against the coal dust pollution in the creeks her grandson played in and the coal waste impoundments that threatened to drown the only community she’d ever known. It happened to Debbie Jarrell, co-director of Coal River Mountain Watch today, whose family name is sprinkled all up and down Route 3: Charles B. Jarrell General Store, Jarrell Backwoods Towing, Perry Jarrell Road, Jarrell’s Ridge. Jarrell first joined the cause around 2005 because her granddaughter was a student at Marsh Fork Elementary, and she kept getting sick. It happened to Larry Gibson, who was so sickened by how mountaintop removal mining had transformed the home that he and his ancestors had grown up in that he walked the length of West Virginia north-to-south to warn fellow mountaineers about the threat.

In January 2011, when Junior Walk had been working as a full-time organizer for just about a year, Judy Bonds died of cancer, her disease believed to be brought about by airborne dust from mountaintop removal in the region. By the end of 2012, Larry Gibson would be felled by a heart attack.

It was around that time that a hydraulic fracturing boom in the Marcellus Shale birthed a crop of new gas wells all across northern West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Natural gas-powered electricity was a cheaper and ostensibly cleaner alternative to coal-fired, but the magnitude of the threat it posed to the climate and the environment became clear: explosions and flares on wells and pipelines, methane leaks, the mysterious cocktail of fracking chemicals that seeped into water tables and tributaries.

In 2014, oil production in the United States jumped by 16 percent to 8.7 million barrels per day, the largest single-year increase in a century, largely due to the fracking boom in the Bakken shale region of North Dakota and Montana. The dangers of oil infrastructure seized public attention in 2010, with the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, and continued to make headlines throughout the decade: the Enbridge pipeline leak into the Kalamazoo River, the largest inland oil spill in history; the deadly derailment of an oil train in Lac-Mégantic, Québec; the Refugio oil spill on California’s Gaviota coast. Meanwhile, coal production in West Virginia had been in steep decline pretty much since 2009.

Back in Raleigh County, things had started to fall apart within the activist community. The deaths of Bonds and Gibson had been a huge blow. Mike Roselle and the younger activists were increasingly at odds over the organization’s hierarchical structure and the ostensible need for increasingly radical tactics, which eventually lead to the youth contingent storming the house in Rock Creek and announcing that they were forming their own movement: RAMPS, Radical Action for Mountains’ and Peoples’ Survival. (Walk is a co-founder of this organization, but no longer involved.) Plans to lobby for a wind farm on top of Coal River Mountain, already a bit of a pipe dream, faded to an increasingly small likelihood.

If you ask Vernon Haltom, the executive director of Coal River Mountain Watch, when the anti-mountaintop removal movement in the Coal River Valley started to lose steam, he’d pin it to 2015. “Some of the big coal companies declared bankruptcy that year,” he explained over the phone. “And then a lot of the press, even some of our allied groups, declared victory, that mountaintop removal was essentially over. And they don’t really get involved with us anymore because we kept saying, ‘No, it’s not, it’s still ongoing.’”

Walk watched as most of his friends trickled off to new battles, primarily against projects such as the Mountain Valley Pipeline. “I can’t really be mad about it,” he says, “because they did what they could, and some of them gave years out of their lives and so much effort to invest in this fight here to help my community, you know what I mean? And so I can’t really feel any other way except grateful for the time that they did spend here.”

But he isn’t interested in joining the pipeline fight. “As long as they want to work against the coal industry and make that their main effort, I’ll be right there working shoulder to shoulder with them,” he says. “But if they’re doing all this other stuff against natural gas and all that, yeah, that’s great. But that’s not where I’m going to put my effort because this is my fight, this is my community and it’s what I do.”

I first met Walk at the Coal River Mountain Watch office, which occupies a simple brick building that used to house a diner on the main street of Naoma, roughly halfway between his parents’ home and Mike Roselle’s. It’s filled with relics of the organization’s 24 years: Bonds’ Goldman Prize, framed newspaper cutouts, photos of protests on the steps of the state capitol in Charleston. Walk is the organization’s only current employee outside of its directors. The office is unheated on this cool April morning. I ask Walk to tell me about what he does these days.

His mission: to catch coal companies in the act of breaking environmental laws, no easy feat. He has spent years intimately learning the land that he’s committed to protect. He’s memorized a whole network of old logging roads, forged back trails on foot up thistle-thick slopes. He’ll go out there with a camera and a drone and take pictures of damaged hillsides or a digging site’s spread onto unpermitted land, and take his findings back to try to goad the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection into doing something about it, also no easy task. Haltom will make use of a small plane from Southwings, another conservation organization, to fly over mountaintop removal projects and document new developments.

On May 15, for example, Haltom and Walk got word that the Little Marsh Fork, which runs into the Coal River, was running pitch-black. Heavy rains had overflowed a stockpile at the processing plant. Haltom had to call the DEP inspector out of church, and Walk ran out to capture the inky water via drone.

“The whole point of it is to make them spend as much money as we possibly can to make it less economically feasible for them to keep mining that coal,” Walk says. “Paying fines, going back on to the site to fix stuff like slips in the hillside or whatever. It’s death by a thousand paper cuts.”

It may surprise those involved in the climate movement today to learn that mountaintop removal mining is not only legal but active. Walk describes new blasts into the mountain as a near-daily occurrence. Later that day he drives me up to a surface mine in a rattling Subaru — a professor he met through his activism traded it to him for a hunting rifle — with the patient resignation of someone who has given the same tour a thousand times.

The Subaru climbs up a dirt road through budding forest, all umber and olive with splashes of violet and sun-yellow. Then suddenly, under a brilliant sky streaked with fast-moving clouds, everything is gray. A surface mine is just coal and rock as far as the eye can see, small heaps of it graduating into foothills. You can see the soft round heads of the surrounding mountains several miles off. We can’t stop the car and get out to walk around because Walk’s vehicle is well-known to any employees of the coal company that might be on site.

He smokes a cigarette on the drive home, and we go to talk to his mother, Shelia.

The nightmare of the Black Eagle mine, next to the Walk family home in Eunice, both mother and son agree, started with the noise. In 2020, Alpha Natural Resources put in an exhaust fan so loud that you couldn’t talk to someone standing two feet away without yelling.

“I’d call the DEP and I’d be like, hold on, let me open the back door and you’ll hear what my problem is,” Shelia recalls. “And they would say, ‘Oh man.’ Yeah, imagine me sitting here!”

It took months of filing reports to the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, but eventually Alpha Natural Resources moved the exhaust fan. That still left the dust — not just coal dust, which Shelia’s lived with all her life on Route 3, but silica dust. One morning this past February, Shelia went to make coffee and found every surface of the kitchen coated in a light white powder. She initially assumed her husband had somehow exploded a bottle of baby powder while taking care of their grandson, but gradually realized what she was looking at. “And if it’s sitting in our kitchen like this, we have breathed it. Oh, my Lord. And it’s scary because that’s what causes cancer.”

Alpha Natural Resources had bought out the couple dozen residents of the village of Pettus, immediately next to Eunice, to knock down their homes and make more space for the Black Eagle mine. Shelia had expected the residents of Eunice would be offered a buyout, too, but it never happened. When she first learned that the mine would be put in, she had no intention of ever leaving her lifelong home. But she’s had enough; living next to an operating coal mine makes her miserable. In June, she and her husband bought a new home with a big garden on a hillside in Horse Creek, about 10 miles away.

Shelia’s neighbors are fed up too, and have joined her in community meetings to demand action from the Department of Environmental Protection against Alpha Natural Resources, which might include a buyout, although that’s an uphill battle. Walk and Vernon Haltom have helped her and other people in Eunice by getting their documentations of dust and noise and other offenses filed with the DEP. I ask Shelia if she thought the anti-coal activist movement of the prior decade had influenced the town’s apparent disillusionment with the coal industry at all.

“A lot of the older people had already realized what the coal company has done,” she says. “And I think that’s where my eyes were starting to open, when I was a young mother, from my grandparents and my dad and just listening to their stories. And once the so-called tree huggers come in, I think it started to open eyes for more people my age. After you hear it a couple times, you’re like, you know, that makes sense.

“And when the company decides they don’t need you no more, you ain’t gonna have nowhere to go hunting, nowhere to go fishing, nowhere to go swimming. And they just leave an empty, flattened place that nothing can grow or live on.”

A couple of weeks before my trip to the Coal River Valley, an unaffiliated group of organizers announced something called the Coal Baron Blockade. It was a planned protest at the Grant Town Power Plant in Marion County, which burns gob — coal waste — bought from West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin’s family’s company, to the tune of a few hundred thousand in profit for Manchin himself every year. Prior to the event, I found it impossible to ascertain the protest’s lead organizer or its specific goals.

I asked Walk if he knew anything about the Coal Baron Blockade. He said it was clear it was organized by out-of-staters, and they had reached out to him and a bunch of other West Virginia activists and asked him to be part of it. He didn’t see reason enough to make the time.

“If the weather’s nice, I need to be out with the drone and catching the coal companies doing illegal things, so that doesn’t leave a lot of time to drive plumb to Morgantown for a weekend when I’m not even on the clock.” He gestured to his Subaru. “You see what I’m driving? I’m not putting more miles on that thing.”

If you ask Walk why he still does this, his answer is simple: He feels he owes it to his predecessors — Judy Bonds, Larry Gibson, Chuck Nelson — because they gave him a purpose, told him they were proud of him, gassed him up.

“Not that I’m self-important enough to feel like I shoulder their legacy or anything like that, because that would be impossible for anybody,” Walk is quick to add. “But somebody’s got to be the voice out here saying, ‘No, that’s wrong, what the coal industry does is bad.’ And that’s just kind of my lot in life.”