Hello, and welcome to the latest edition of Record High. I’m Siri Chilukuri, a reporting fellow at Grist. Today, we’re covering the dire impact of extreme heat on livestock and the agricultural industry — as well as a potential solution some farmers are trying to save their herds.

Livestock like cows, goats, sheep, pigs, and others are susceptible to the same types of heat-related illnesses as humans, including dehydration, heat exhaustion, and heat stroke. As temperatures have climbed in recent years, so too have their impacts on the country’s vast livestock populations. Last summer in Kansas, a heat wave killed over 2,000 cattle when temperatures hit 104 degrees Fahrenheit. This summer, hundreds of cattle have died in Iowa in late July because of extreme heat and humidity.

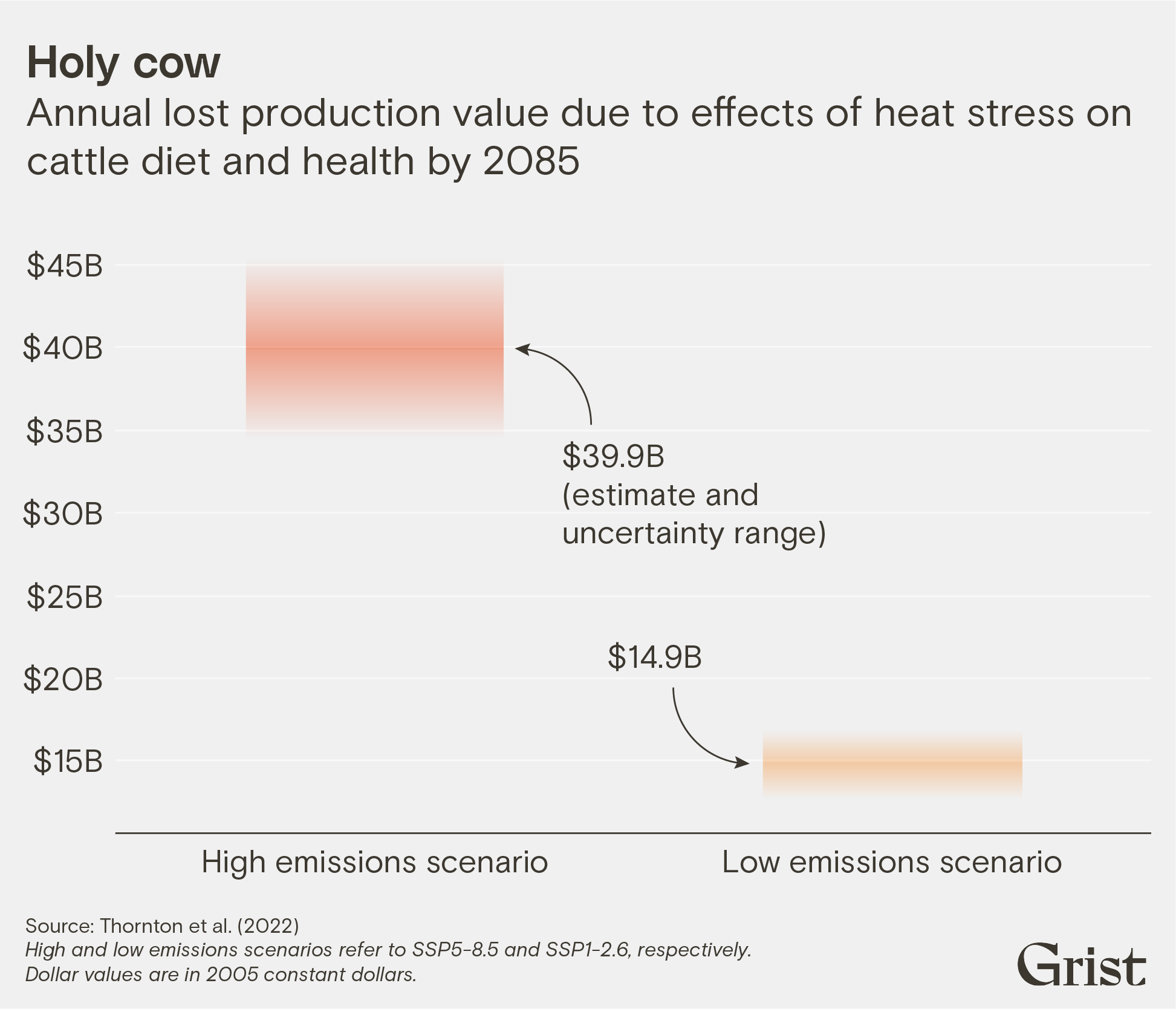

By mid-century, America’s heartland could form part of an “extreme heat belt” that stretches from Texas to Chicago, up the central United States, experiencing heat index conditions of 125 degrees F or more, according to the nonprofit climate research organization First Street Foundation. Scientists also estimate that losses from livestock heat-stress could reach almost $40 billion per year by the end of the century. Add worsening drought conditions and its impact on food availability, and livestock and the farms that own them have a difficult stretch ahead.

Farmers are now searching for solutions on how to keep their animals safe. One such method is something known as silvopasture, which incorporates trees — often harvestable fruit or nut trees — and grazing on the same land, Grist contributor John McCracken reports today.

Shade during extreme heat is crucial to keeping core body temperatures low enough to maintain vital systems. This is as true for livestock as it is for humans. For beef and dairy cows, of which there are 89.3 million in the U.S., ideal body temperatures range from 44 to 77 degrees F, according to the Department of Agriculture, or USDA. Above those, heat stress causes cattle to produce less milk and decreases their fertility.

In Missouri, farmer Josh Payne is introducing shade in the form of chestnut trees, planting 600 of them across the same fields his cattle graze. The trees are a long-term solution and will take time to reach their full shading potential, so in the meantime, Payne is using mobile shades to protect his animals. But he’s counting on the trees to protect his farm and animals in the long run — both from extreme heat and as a way to help counter climate change.

Silvopasture can improve soil health and increase a field’s uptake of carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. An estimate from the nonprofit climate solutions organization Project Drawdown predicts that the method could sequester five to 10 times more carbon dioxide than a pasture without trees.

A USDA survey from 2017 showed that only 1.5 percent of U.S. farmers practice any kind of agroecology, the ancient regenerative farming movement that includes silvopasture. In Illinois, the nonprofit Savanna Institute has been funding projects to help farmers better understand how to do silvopasture more effectively, and uses similar methods to Payne’s, notably planting chestnut trees.

As McCracken writes, “Planting trees in a field seems almost too simple as a way to keep livestock safe and healthy in a hotter world.” But researchers know better, he notes. Silvopasture is complicated, as it requires a delicate balance between planted trees, natural forests and brush, and livestock. But as farmers grapple with worsening extreme heat, it can be successful because of its flexibility.

“Silvopastures are not a silver bullet, but at this point, I don’t think we have any silver bullets anymore,” Ashley Conway-Anderson, a researcher at the University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry, told McCracken for Grist.

By the numbers

A recent study in the journal The Lancet examined the economic damage heat stress will have on cattle under various climate scenarios. The animals comprise a key part of the agricultural sector, accounting for 17 percent of industry revenues in 2022, according to the USDA.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

What we’re reading

A loneliness epidemic is causing heat waves to be more deadly: Americans are now more socially isolated than ever before, with only 3 in 10 people knowing their neighbors. In a crisis, though, neighbors and friends can be the first line of defense to help. As this summer’s record-breaking heat continues, my colleague Akielly Hu looks into how isolation and extreme heat are killing people, and some possible solutions that cities are taking to tackle the issue.

Arizona declares extreme heat emergency: Governor Katie Hobbs of Arizona declared a state of emergency on Friday, due to the state’s sky-high temperatures. In Phoenix, the city’s longest-lasting heat wave spanned the entire month of July. The declaration will free up funding from the state for cities and municipalities to tackle the issue of extreme heat, Jessica Boehm reported for Axios. Additionally, as my colleague Zoya Teirstein reported last week, extreme heat has inundated the city’s emergency rooms, with people experiencing burns from falling on the sidewalk, severe dehydration, and other heat-related illnesses

A long-lasting marine heat wave is endangering ocean ecosystems:

Starting in 2013, a phenomenon known as “the Blob” formed in the northern Pacific Ocean, with ocean temperatures increasing by 4 to 10 degrees F. It was the largest and longest marine heat wave on record and caused havoc for fisheries. Salmon, cod, crabs, and many other species declined as temperatures rose, causing billions of dollars in economic damage. As my Grist colleague Max Graham reports, marine heat waves such as the Blob are becoming more common and more severe, endangering not only marine life, but also the coastal communities reliant on fisheries for their livelihoods.

Extreme heat could threaten unborn children: Researchers have long known the serious toll that extreme heat can have on the human body, but until recently, two groups remained largely understudied: unborn children and pregnant people. New research finds connections between scorching temperatures and a slate of health concerns for these vulnerable populations, from preterm birth to low-birth weight to other conditions, like stillbirths. One study from 2022 found that for every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees F) of warming, there was a 17 percent increase in fetal stress, usually an increased heart rate or decreased blood flow, Grace Browne reports for WIRED.

Does extreme heat spell the end of the European summer vacation?: Record-breaking heat in Europe this summer has been interfering with travelers’ plans, Ceylan Yeginsu reports for the New York Times. Yeginsu herself experienced 113 degree F temperatures when attempting to vacation in Turkey, and travelers in Italy and Greece have also faced scorching heat. This summer marks the latest in a few years of hotter summers for the continent, with last year’s heat wave killing an estimated 61,000 people, according to a study I reported on earlier this summer.