Hello, welcome to Record High. I’m Kate Yoder, a staff writer at Grist, and today, we’re looking at how sweating can help us cope with climate change.

It is embarrassing to be a sweaty person. I remember making my way to the podium to give a speech at my sixth-grade graduation, my feet squelching audibly in flip-flops with every step; taking a test and noticing the warped paper beneath my moist hand; standing up from a plastic chair and hoping no one noticed the sweaty butt print I left behind. So it came as a relief to learn that sweating was actually good for something.

Once I learned that the science journalist Sarah Everts wrote a book called The Joy of Sweat, I knew that I had to talk to her. Everts makes the case that perspiration is a human superpower, a gift for enduring sweltering temperatures. “I think it’s funny that humans have this enormous taboo about a biological function that’s ultimately going to help us survive climate change,” she told me.

The science of sweat goes as follows: At the first hint of getting hot, your heart starts pumping blood toward the outskirts of your body. In tandem, sweat glands pump water — drawn from that blood — onto your skin. When those tiny beads evaporate, they move heat off the body and into the air. It’s an incredibly efficient way to cool down. The geneticist Yana Kamberov, who studies the evolution of sweat, told me that the ability to shed buckets of water is an ability as unique to humans as our oversize brains.

So why do we burn through all that water, one of life’s precious resources? To avoid getting cooked from the inside out. “Dying from a heat wave is like a horror movie with 27 endings that you can choose from,” said Camilo Mora, a climate scientist at the University of Hawaiʻi at Manoa, who has cataloged 27 different ways that heat can lead to organ failure and death.

“Dying from a heat wave is like a horror movie with 27 endings that you can choose from.”

The thing is, sweating has its limits, as I reported for Grist this week. Very hot, humid conditions can render it ineffective. When the air is thick with water molecules, it’s harder for sweat to evaporate, and the body starts overheating. The theoretical point at which no amount of sweating can help you is thought to be six hours of exposure to a “wet-bulb temperature” of 35 degrees Celsius, or 95 degrees Fahrenheit. Wet-bulb temperature — invented by the U.S. military in the 1950s after recruits kept collapsing from heat illness — is a measurement that combines heat and humidity with sunlight and wind.

But heat gets dangerous long before that point. Last year, a study found that the upper limit of safety for healthy people was a wet-bulb temperature of 31 degrees C, or 88 degrees F. And factors like age, illness, and body size change the math. Older people are especially vulnerable — partly because of health conditions, and partly because sweat glands tend to deteriorate with age.

That humidity poses a problem for sweating is well-known, but I was surprised to learn that the opposite extreme — hot, dry air — could present its own set of problems. Sweat evaporates very quickly in arid conditions, but the human body can only produce a limited amount of sweat, said Ollie Jay, a health professor at the University of Sydney in Australia. That limit is about a liter per hour at rest, or about three liters an hour during exercise. If you managed to reach that point of maximum sweatiness in dry heat, then you wouldn’t be able to sweat enough to cool down. But most climate models ignore this, leading almost certainly to overestimates for what humans can handle, Jay said.

Given how crucial perspiration is for survival, you’d think researchers would have the science of sweat all figured out by now, but there are still open questions. Read the full story here. (Teaser: It includes a robot that sweats.)

By the numbers

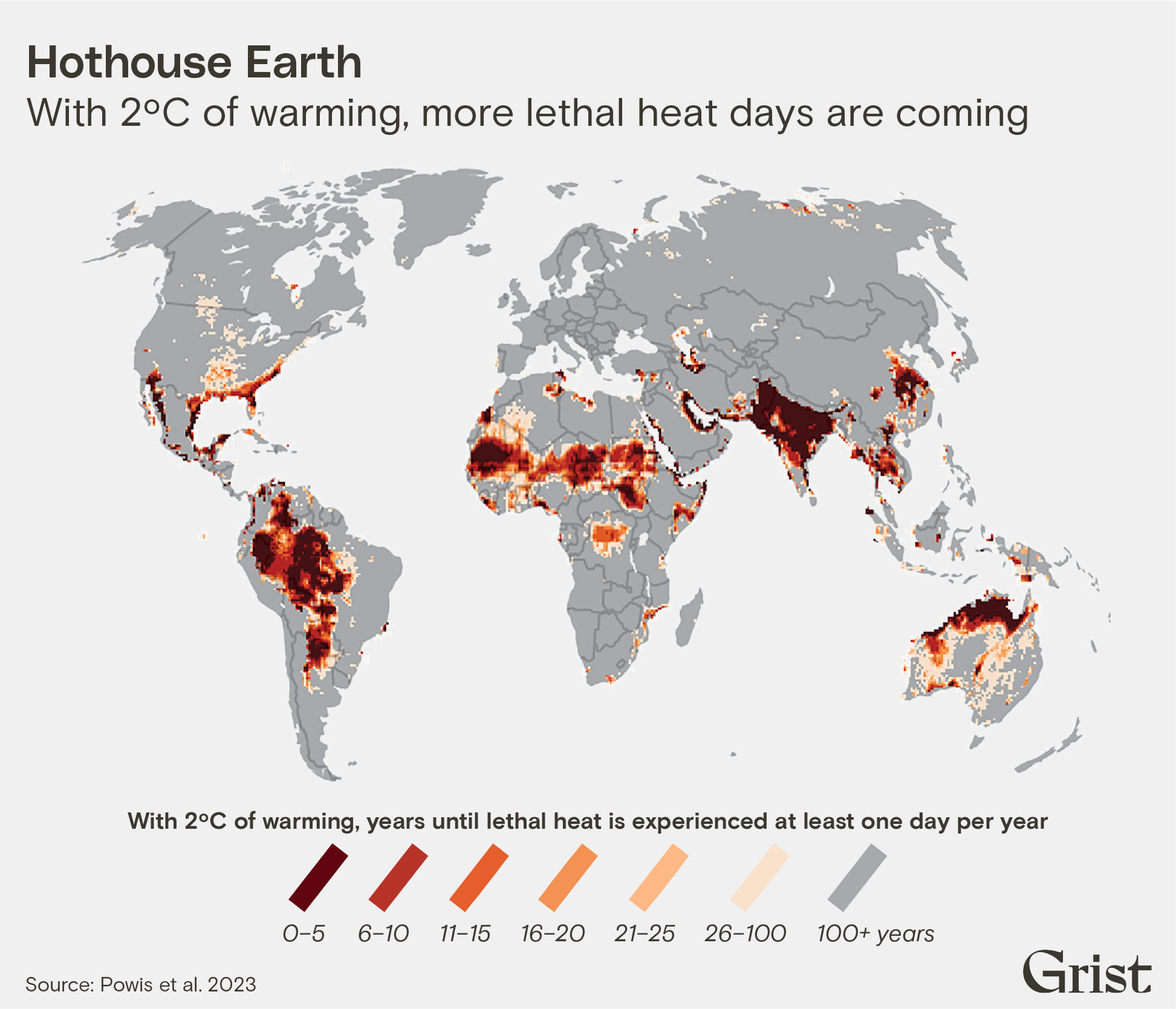

Earlier this month, researchers analyzed the hot and humid conditions under which the human body starts to overheat unless specific actions to cool down are taken. They found that under our current climate, 8 percent of the land on Earth will meet this threshold at least once a decade. That would increase to a quarter if global temperatures warm 2 degrees C above the preindustrial average.

Data Visualization by Clayton Aldern

What we’re reading

It’s not only coral in trouble in Florida: Anemones, sponges, and jellyfish — usually resilient creatures — are struggling to survive in the Everglades amid record marine temperatures. “It’s a complete ecosystem problem,” Matt Bellinger, owner and operator of Bamboo Charters in the Keys, told Abigail Geiger and Gabriela Tejeda for their piece in Grist.

Take a siesta: A midday break with a meal and a nap doesn’t just sound pleasant, it also protects outdoor workers from exposure to the hottest time of day. Grist fellow Siri Chilukuri explains the benefits of reviving the Mediterranean tradition and the challenges of bringing it to the overworked United States.

The fight for worker safety heats up: After laboring in temperatures up to 118 degrees F, baggage handlers, runway signalers, and cabin cleaners at the Phoenix airport requested an investigation of working conditions they say leave them prone to heat illness and exhaustion. They are the first airport workers to file a complaint with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Grist fellow Katie Myers reports.

Heat waves and pregnancy are a dangerous combo: Exposure to both short- and long-term heat raises the risk of life-threatening complications during labor and delivery, Jessica Kutz reports for The 19th. A recent study found that extreme heat was associated with a 27 percent increase in “severe maternal morbidity,” a category that includes cardiac arrest, eclampsia, heart failure, and sepsis.

An “extreme heat belt” is emerging in the Midwest: When hazardous heat came to Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska in August, emergency rooms saw a record number of people suffering from heat-related illnesses. Many homes in the region are designed in a way that’s ill-prepared for hotter temperatures, Holly Edgell writes for Kansas City’s KCUR.