Off the northeast coast of Brazil, the hot morning sun reflects off the sea’s surface as a jangada, a traditional wooden fishing boat, sways gently in the rolling waves. There’s just enough room on the vessel for the team from Biofábrica de Corais, a coral conservation and research group, to sift through the piles of sea ginger coral fragments they’ve collected from the ocean below them.

Without any sides, the boat allows salty water from the Atlantic to lap onto the researchers as they sit cross-legged on its floor. The four are moving quickly to examine the tiny invertebrates, keeping them in plastic bins filled with ocean water to ease their stress.

Rudã Fernandes, a biologist and founder of Biofábrica de Corais, turns a fragment of coral over in his hand, holds it up in front of his face, then sets it in one of the bins. Next to him, Luis Carlos Manoel dos Santos, better known as Melado, reaches into the salty water and picks it back up. The jangadeiro, or fisherman, has lived and worked in the region his entire life, and this is his boat. Before joining the team, he used it strictly to take tourists on trips around the reef in the small beach community of Porto de Galinhas. Now, it serves a dual purpose, carrying scientists and volunteers on weekends and in off-hours to monitor the coral they’re working to save.

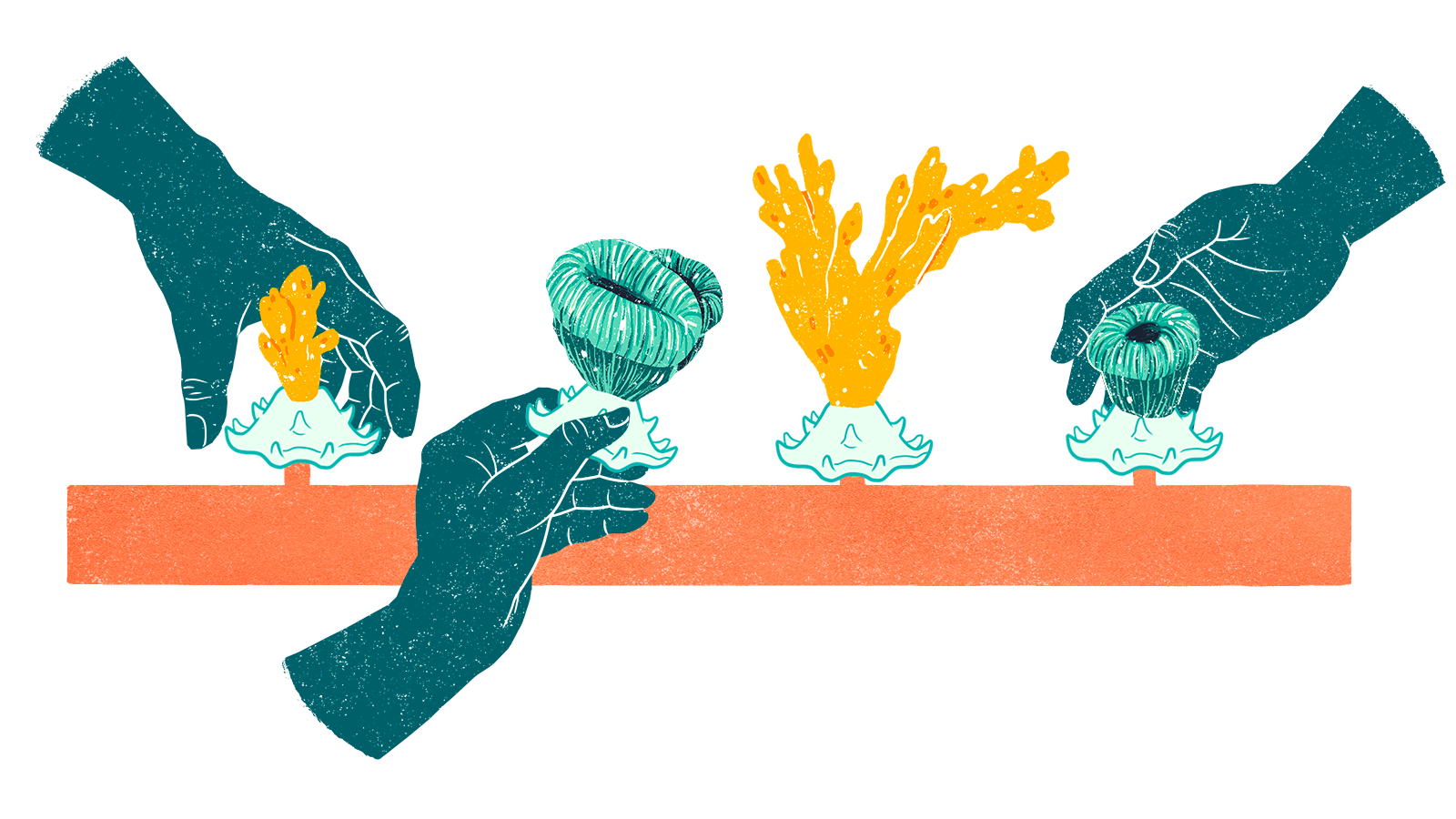

Holding a piece of sea ginger, or Millepora alcicornis, between his index finger and thumb, Melado squeezes a dab of adhesive to its base and fixes it to a small piece of white bioplastic. The structure is known as a “crib.” Created by Fernandes as part of his doctoral dissertation, the 3D-printed plastic holders act as temporary living quarters for dying coral. Each one has a species-specific design. Sea ginger, for example, prefers a round crib with small peaks it can latch onto. Cauliflower coral, or Mussismilia harttii, likes to spread out as it grows, so it prefers a crib with a smooth surface and fewer nooks and crannies to hold on to.

These cribs give coral a safe space to recover from the heat waves, bleaching events, sedimentation, and other disturbances that have battered the reef off the coast of Porto de Galinhas. And once the coral is nursed back to health, they can also be placed on rocky surfaces underwater to encourage new extensions off the reef.

This isn’t the first time 3D printing has been used in an attempt to restore damaged and dying coral reefs. Similar projects are being implemented off the coasts of the United States, the Maldives, the Mediterranean, the Caribbean, Hong Kong, and elsewhere. But Biofábrica de Corais’s approach is different in two ways: First, Fernandes’ design is cheap — incredibly cheap. Each coral crib costs an average of 28 cents USD to make, making the project financially accessible to communities and scientists across the globe.

The effort also doesn’t just rely on its crew of scientists. Biofábrica de Corais has involved the entire community of Porto de Galinhas in its restoration efforts, saving not only the coral reef and the ecosystem it upholds, but also the local economy that depends so heavily on the health and survival of the soft-bodied colonial animals.

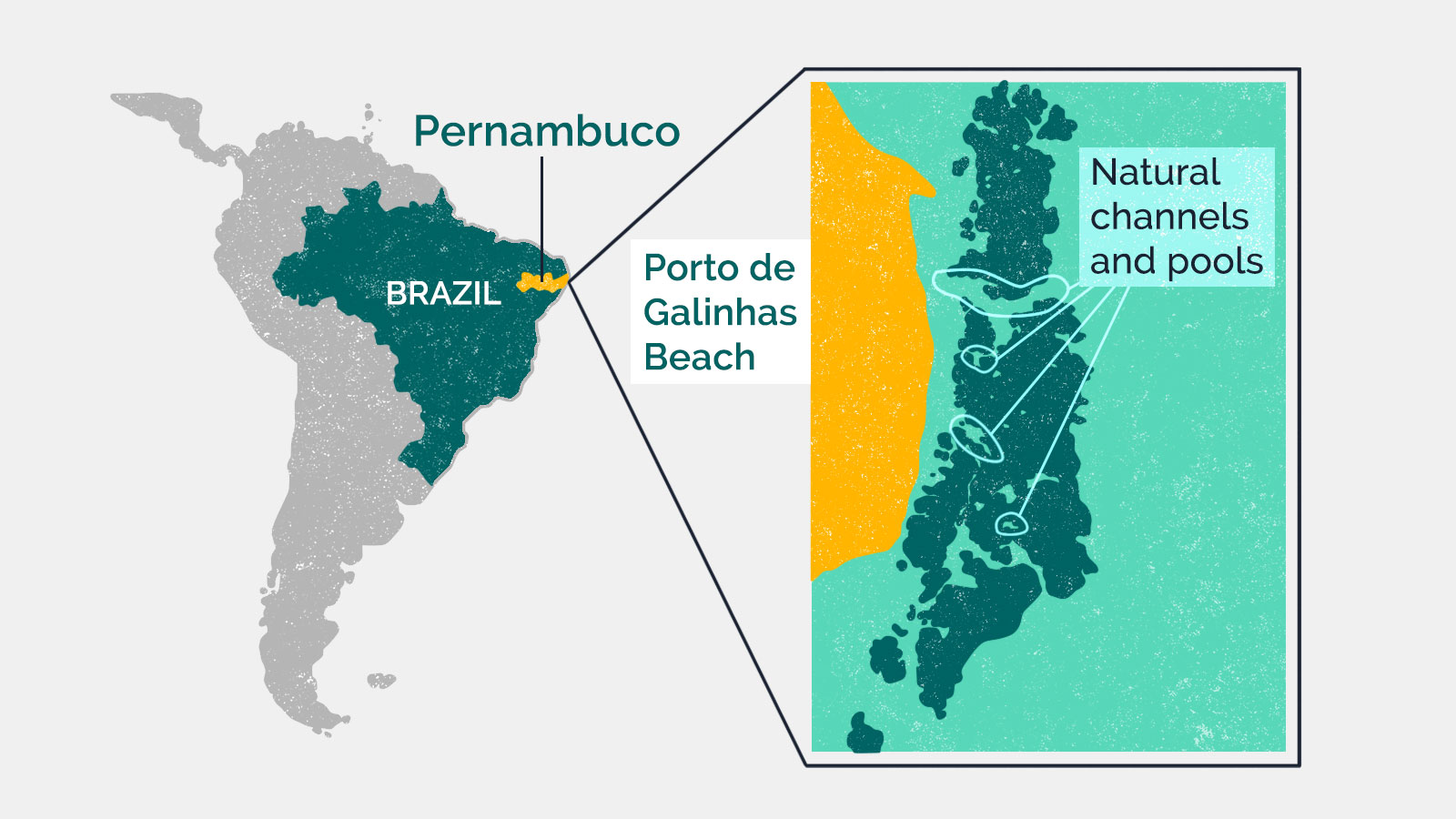

Brazil’s coral ecosystems — the only reefs located in the south Atlantic Ocean — are comprised of a network of small reefs scattered along some 1,864 miles of the country’s coast. The majority are located along its northeast coast, from the state of Maranhão to the southern tip of Bahia. The reef in Porto de Galinhas, where the Biofábrica de Corais team works, is just 1 mile long.

It’s difficult to pinpoint just how many species of coral there are in the world. By nature they are ever-changing, and their number has yet to be studied deeply. But what is known is that Brazil has a relatively low diversity of corals compared to other regions. According to the 2020 Status of Corals of the World report, there are 23 species of hard coral and five species of hydrocoral, coral-like creatures, in the country — nine of which are endemic to Brazil and all of which are crucial to the survival of their ecosystems. Along with sea ginger, they include rose coral (Meandrina braziliensis), cauliflower coral (Mussismilia harttii), and star coral (Siderastrea stellata).

And like all coral species around the world, they are under threat.

While reefs are suffering because of a variety of factors — overfishing, pollution, and ocean acidification among them — it’s widespread warming that is causing the most concern, as sea surface temperatures have slowly ticked up over the last 100 years.

Over half of the world’s coral reefs have already been lost. A 2018 report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated that up to 90 percent of coral reefs could be lost if the world warms by 1.5 degrees Celsius.

The first major modern global bleaching event happened in 1998, when roughly 8 percent of the world’s coral was killed. A second followed in 2010. According to Rebecca Albright, a coral biologist and curator at the California Academy of Sciences, both were prompted when El Niño conditions worsened already warming waters. The most extensive bleaching event lasted from 2014 to 2017, affecting 70 percent of the world’s coral reefs and damaging two-thirds of Australia’s famous Great Barrier Reef.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, the leading cause of coral bleaching is climate change. Corals can survive bleaching events, but they sometimes need more than a decade to fully recover. That kind of time isn’t something they can always count on.

That’s why a growing movement of innovative research projects like Biofábrica de Corais is working hard and fast to find the best ways to save corals that have already been bleached and to prevent the animals from suffering again.

The reefs off the coast of Brazil were mostly spared during recent worldwide bleaching events — Abrolhos reef, farther south and off the coast of the state of Bahia, suffered less than 3 percent of coral cover loss due to bleaching and mortality between 2014 and 2017. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t suffered.

In 2020, the reef off Porto de Galinhas suffered a major localized bleaching event, leaving its coral populations clinging to life.

Fernandes estimates 90 percent of the sea ginger coral was affected by El Niño, increasing the water’s temperature to more than 32 degrees C, or 89.6 degrees Fahrenheit. The other species the team works with — cauliflower coral, which is endemic to Brazil and on the country’s red list for species threatened with extinction — was 100 percent affected.

Already struggling because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the community was devastated. Heavily reliant on tourism because of the coral reef, they didn’t know how they would bounce back.

“We already knew in December 2019 that the bleaching was coming,” Fernandes said, “but we didn’t have the power then to do anything about it, to protect what we had already saved.”

By that point, the researchers and community volunteers had already worked tirelessly for years to help the local coral thrive. When Fernandes, originally from Rio de Janeiro, first started his research in 2015, he wanted to develop better technology for fish-keeping at home. It was his time in Porto de Galinhas that made him realize the need to focus on coral conservation, well before he witnessed bleaching events in the community. The worldwide events in previous years were enough to make him concerned about what would happen to his new home’s reef if water temperatures were to rise significantly.

Each fragment of coral — often plucked from the ocean floor, damaged, but still alive — is affixed to a species-specific crib with a dab of adhesive. The crib is then clipped onto a matching piece glued to a long structure made of PVC pipes the team calls “tables.”

Once several tables are full, creating what is referred to as a coral nursery, the team takes them to what they call a farm — a pre-selected area off the coast where divers place them at the bottom of the sea and monitor them regularly. The ideal location for a farm is one without a lot of sediment or powerful waves. It also needs to have a depth of at least 6.5 feet to keep the corals comfortable. After 90 to 150 days in a farm location, the corals and their cribs are unclipped and brought to other carefully chosen areas, like rocks and other parts of the reef, where they will best thrive and continue to grow.

But in 2020, the team ran out of time. During the bleaching event, Biofábrica de Corais lost entire nurseries of coral before they could even be transplanted.

“It showed us that we needed to continue to improve the model,” said Vinícius Nora, a conservation analyst at the World Wildlife Fund Brazil’s Marine Program, which has provided funding for Biofábrica de Corais.

He and other World Wildlife Fund Brazil partners are currently studying the possibility of creating coral reserves in aquariums as a way to guarantee that species won’t go extinct. Their focus, however, remains keeping as many corals as possible in the Atlantic Ocean

When Fernandes first started designing cribs at the Federal University of Pernambuco’s Luiz Accioly Enzymology Laboratory, known as LABENZ, he had no idea his project would turn into a startup shaped by and for his community.

The research he started at LABENZ is essentially ongoing. A lot of what he and the rest of the team at Biofábrica de Corais do — figuring out the shape and size of crib each species of coral prefers, finding just the right spot off the coast where the invertebrates will thrive — is trial-and-error.

“There will always be research to do,” he said. “We’ll always have more to learn.”

The 3D printer the team uses is at LABENZ, located in the state capital of Recife, about an hour-and-a-half drive from Porto de Galinhas. A biologist named Ranilson Bezerra runs the lab and is an integral part of Biofábrica de Corais, overseeing the scientific research backing the team’s work in the field and the master’s thesis of Maria Gabriela Moreno Avila, a Venezuelan biologist and ecologist. Avila does much of the diving for Biofábrica de Corais, collecting damaged coral fragments from the ocean floor so that they can be revived. She’s joined in this work by Amaro Damasio, a native of Porto de Galinhas who works as an environmental officer for the city and is known to most as Barrão.

It’s not just the science that has Bezerra invested in this project. For decades he has been visiting Porto de Galinhas and a neighboring community called Maracaípe, where his family has a home. He has spent many hours diving in their waters and studying the species that live there.

“I want my grandchildren to have all of this too,” he said. “These types of projects are so important, so necessary. I wish there were 30 Biofábrica de Corais.”

Aside from running the 3D printer, he and his students are now researching new ways to feed corals. They plan to test several methods, from releasing food particles at the water’s surface and allowing the invertebrates to collect it with their tentacles to a new technique involving syringe feeding. Nutrient-filled foods are also being developed at the lab, using remnants from fish and other marine life left behind by fishermen who know those parts won’t sell.

“We don’t just want to develop the best diet for them,” said Bezerra. “We have a hypothesis. We want to see how this diet might have an effect on bleaching.”

If the coral were to disappear, it wouldn’t be long before Porto de Galinhas would fade away too.

Just 650 feet from the beach, its reef is a tourist hotspot, keeping the community’s economy alive. Most of the residents of the village — a part of the municipality of Ipojuca, which has a population of just over 99,000 — depend on the roughly 1.2 million visitors it sees every year.

The 2020 Status of Corals of the World report notes that globally, “the value of goods and services provided by coral reefs is estimated at US$2.7 trillion per year, including US$36 billion in coral reef tourism.” The report is produced by Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network, a collaboration between scientists, governments, and the United Nations.

Melado, the fisherman who accompanies the scientists on their dives, is one of 84 jangadeiros who work in Porto de Galinhas, giving tours of the shallow waters surrounding the coral reef. There are 80 stands set up along the beach, selling wares including food, drinks, beach toys, and bikinis. More than 1,000 independent salespeople also walk the sand selling similar items. Another 19 diving companies operate on the water, with floating wooden platforms where tourists can rent masks, snorkels, flippers, and oxygen tanks in hopes of seeing sea creatures up close.

Maria Dolores Serravalle runs one of those companies. Originally from Argentina, she’s been living in Porto de Galinhas for three years and runs her business with a licensed diver. She fell in love with the community, the Atlantic Ocean, and the marine life that calls it home when she first visited 16 years ago.

Now, her livelihood depends on what drew her to Porto de Galinhas. She first heard about Biofábrica de Corais through Melado and started following their work on his Instagram. When she witnessed what happened to the coral during last year’s bleaching event, she was horrified. It made her want to pitch in to help Biofábrica de Corais protect the reef.

“Everyone should be helping,” Serravalle said as she sat under a beach umbrella, taking a break from walking the white sand where she spends her days telling tourists what her business has to offer. “It’s a piece of heritage for future generations. It has to be preserved. We all depend on the coral. Without it, we would have nothing.”

She loans dive equipment to Biofábrica de Corais whenever she can and provides them with oxygen tanks at a discounted price. Her company, Neptuno Dive, has also pitched in with research, monitoring, and measuring the growth of coral. They also bring photos back from their dives so that Fernandes and his team can keep track of their fragments even when one of them isn’t able to check on them.

Others support the team and its work in a more indirect way. At each entrance to the beach there are a handful of kiosks, most selling souvenirs and beachwear or operating as restaurants. One of those restaurants is run by Vera Lucia dos Santos. A favorite spot for locals, including the Biofábrica de Corais team, the restaurant serves hot coffee, cake, and lunches freshly caught by Santos’s husband.

Every time the team comes back from an early-morning dive to check on the coral nurseries, they stop to eat, chatting with Santos as she brings them plates overflowing with rice, beans, farofa, spaghetti, potato salad, and the catch-of-the-day.

Even after living in the community for 30 years, Santos still loves going out on the water on her husband’s jangada to see the coral. She has learned a lot more about them since meeting Fernandes two years ago — and still remembers the day the team came back from a dive after the bleaching event last year. They brought a coral fragment to show her.

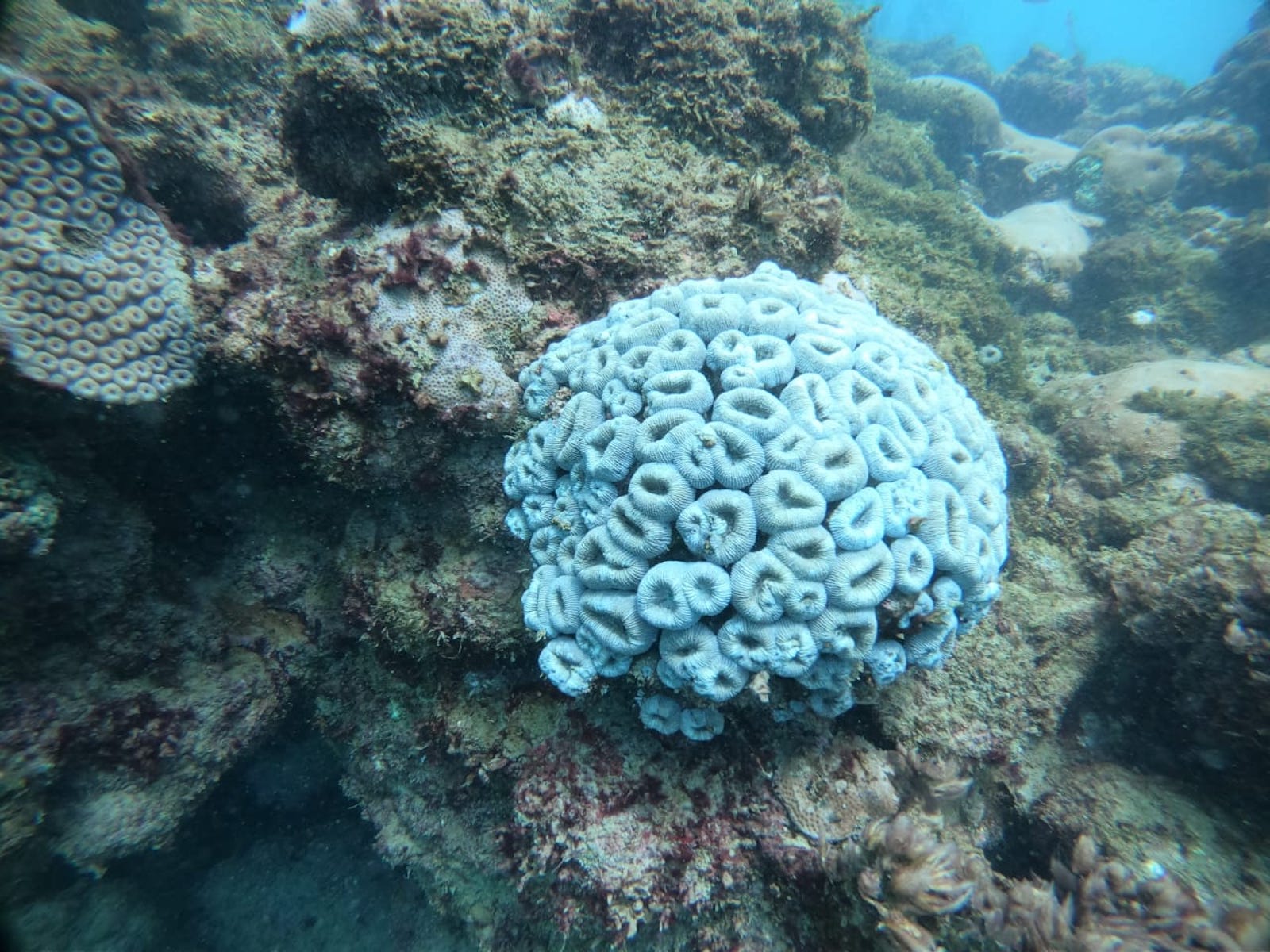

“It hurt my heart to see how white it was,” Santos said.

She worries the reef will be gone before her future grandchildren are able to see it. The majority of her income comes from her restaurant, and other members of her family depend on it too: She employs two of her sisters, one of her daughters, and her stepdaughter.

Luckily, there is still coral to be saved.

The sea ginger the team is examining on the jangada should be a deep yellow. Instead, most of the fragments they’ve collected are a muddy brown. They’re not well, but they’re still alive.

The water here has become turbid because of changing tides, and the team wants to move the coral fragments they’re collecting somewhere clearer, where they’ll have better chances of survival and be easier to manage.

“If we move forward a bit more there’s a spot that’s been a lot calmer lately,” said Melado, maneuvering the boat’s sail to take them there. As a jangadeiro, it’s his job to understand the ocean, how it behaves and how it changes. Turbulent seas mean lots of sediment, and that can lead to murky waters.

As the jangada slowly coasts in the direction Melado pointed to, Fernandes examines each fragment that was just pulled out of the water. The others work quickly and carefully to attach those that are still alive to one of the hundreds of cribs in the bag next to them.

To ensure the project’s sustainability, Fernandes knew Biofábrica de Corais couldn’t remain solely a research project. Now entering its second phase, he’s relying on his team’s expertise to turn it into a startup. His plan is to create workshops to train tourists to transplant coral fragments, teaching them about the animals, the threats they face, and how the cribs could be a solution.

Courtesy of Biofábrica de Corais

Jangadeiros in the community are already on board, and will be in charge of giving visitors tours of the reef — showing them what healthy and damaged coral looks like, and the work they’re doing to save them — while companies like Neptuno Dive will work with them to provide equipment and teach tourists how to use it. A biologist will be on site for the entire process, answering questions and offering scientific information. Fernandes is also in talks with some local hotels about providing the team with a home base, where they will do hands-on training, showing tourists how to safely handle the corals and how to properly attach them to the cribs and tables.

The entire plan — from the creation of the cribs, to transplanting corals, to involving local businesses and tourists — is something Fernandes says can be replicated anywhere in the world.

He and Melado sit at a plastic table at Santos’s restaurant, a wide parasol protecting them from the midday sun as they map out the best and safest routes around the reef for the initial educational tour. They pinpoint ideal places for stops, Fernandes looking to Melado for his expertise on how the jangadeiros will be able to maneuver their boats. With their changes sketched onto paper in pencil, it will be up to Avila to officially update the map, which is part of one of several studies they’re preparing to submit to scientific journals.

Fernandes and his team plan to start running tours in May. The group has already set up a base for its operations, floating in the Atlantic, and is finalizing permissions with the local government.

“I have a lot of dreams,” said Fernandes. “This is just the beginning. If this takes off, I hope we can do something similar with other marine animals too. If we can get everybody involved in conservation, maybe we’ll be able to make a difference.”