On Friday, Microsoft released the results of an independent study it commissioned exploring the environmental benefits of making its devices easier to repair. Its conclusions affirm what right-to-repair advocates have been saying for years: Fixing devices instead of replacing them reduces both waste and the emissions associated with manufacturing new ones.

Based on these findings, Microsoft will be taking actions to enable greater repairability of its devices by the end of the year, as stipulated in an agreement the tech company reached with investor advocacy nonprofit As You Sow last fall.

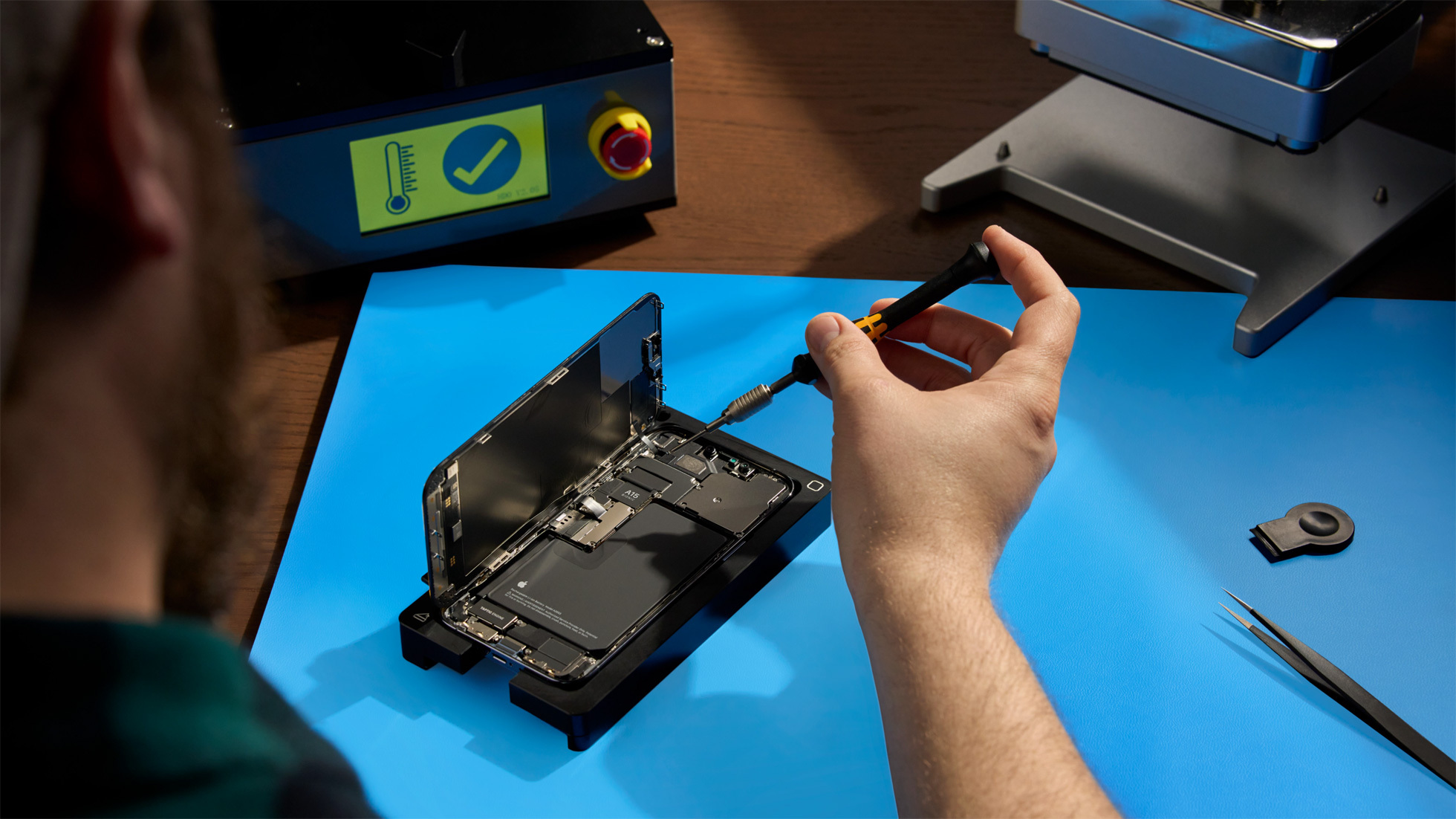

Microsoft’s study release came just two days after Apple launched “Self Service Repair,” a first-of-its-kind program that allows owners of recent iPhone models to order genuine Apple parts and tools to conduct basic smartphone repairs, like screen and battery replacements, at home. More such programs are coming: In late March and early April, Samsung and Google announced plans to sell genuine parts for smartphone repairs via partnerships with the repair guide site iFixit. Both of those programs appear on track to launch in the next few months.

From a consumer perspective, these actions are small steps toward a world in which tech titans actively facilitate repair of their products rather than standing in the way of it. Companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Google have not only historically designed products that are hard to fix, but also have a well-documented history of fighting bills that would support consumers’ right to repair them. For these corporations, repair audits and programs represent a major shift in policy that would not have come about without a mix of public and shareholder pressure, as well as the specter of looming laws and regulations aimed at curbing Big Tech’s anti-repair practices.

Companies are also changing their tune on repair because restricting it is increasingly at odds with their climate and sustainability goals, something shareholders have been keen to point out.

Microsoft’s new repair study affirms that independent repair has tangible environmental benefits.

Conducted by technical consultancy Oakdene Hollins, the study looked at how facilitating repair through design changes and an increase in repair options would affect the waste and carbon emissions associated with Microsoft Surface Pro, Surface Book, and Surface Laptop Studio devices. According to a summary Microsoft published today, repairing Microsoft products instead of replacing them can reduce waste and carbon emissions associated with manufacturing new devices by up to 92 percent.

The study found greater greenhouse gas emissions reductions when consumers had access to local repair options, underscoring the importance of supporting independent repair businesses and allowing capable fixers to repair their devices at home.

Tech companies aren’t waking up to the environmental benefits of repair all on their own. As As You Sow investor advocate Kelly McBee previously told Grist, when she first reached out to Microsoft about its restrictive repair policies last spring, the company told her it saw no connection between repairability and sustainability. When she met with Microsoft earlier this month to review the results of its study — which came about through a shareholder agreement As You Sow and Microsoft reached in October — Microsoft’s attitude had changed.

“They actually thanked us for bringing this to their attention,” McBee told Grist. “Which was a really different vibe from the first meeting — and they acknowledged that as well.”

McBee is optimistic that Microsoft will follow through with the second part of its shareholder pledge, to act on the results of its study by the end of 2022. She noted that the company has already taken a few steps toward enabling independent repair, including releasing a video showing how to disassemble its Surface Laptop SE in January, and launching a program in December that allows independent repair professionals to purchase Microsoft service tools from iFixit.

“By the end of 2022, we will have expanded options in place for customers to have their devices repaired,” a Microsoft spokesperson told Grist in an emailed statement. “Independent repair is one piece of this portfolio of repair options and, by the end of 2022, we will undertake a limited pilot program to enable repair of certain devices by qualified independent repair shops.”

As Microsoft was negotiating a shareholder agreement with As You Sow last fall, Apple was facing a similar shareholder resolution introduced by the mutual fund company Green Century — one that asked the iPhone maker to “reverse” its anti-repair practices in order to bolster its climate commitments. While Apple initially tried to block the resolution, it instead wound up announcing its plan to launch the Self Service Repair program just in time to prevent the resolution from moving forward with the Securities and Exchange Commision, the federal investor protection agency.

Apple has been tight-lipped about Self Service Repair since announcing it last fall, and before this week, Apple fans were starting to wonder if the company had forgotten about it. Now that it’s live, the repair community will be scrutinizing the program closely. Already, iFixit has raised concerns about how Apple parts are paired with individual devices based on their serial number — something that could allow Apple to restrict the use of those same parts to fix other phones in the future. Apple didn’t respond to Grist’s request for comment on this concern.

The Self Service Repair program is also limited in scope, offering spare parts, repair tools and manuals only for Apple’s iPhone 12 and 13 lineups as well as the third generation iPhone SE — and only for U.S. customers. But Apple says it will be expanding the program to additional countries, as well as adding manuals and tools to repair M1 Mac computers, later this year.

Despite the limitations of Apple’s program, its existence is symbolically a big deal. “For good and for ill, Apple has a huge influence on the behavior of competitors,” Nathan Proctor, who heads the right-to-repair campaign at the nonprofit U.S. Public Research Interest Group, told Grist. Apple’s effective capitulation to the right-to-repair movement last year by agreeing to launch a self-repair store very likely “turned up the heat on other companies,” Proctor says.

That includes Google and Samsung, both of which now have self-repair programs in the works. The Samsung program, which the company says is slated to launch this summer, will allow owners of a Samsung Galaxy S20 or S21 smartphone or a Galaxy Tab S7+ tablet to purchase genuine display assemblies (screens with a glued-on battery), backglass, and charging ports via iFixit. The Google program, which will make genuine screens, batteries, and other parts needed for Pixel smartphone repairs available through iFixit, is also on track for the summer, iFixit CEO Kyle Wiens told Grist. The companies, Wiens says, have been enthusiastic partners on these programs, offering feedback on iFixit’s latest Samsung and Google repair guides in addition to developing the replacement parts pipeline.

Green Century shareholder advocate Annalisa Tarizzo, whose firm also filed a proposal with Google asking the company to increase access to repair, told Grist that Google has agreed to meet with shareholders twice over the next year to “talk through more details” of the program, something she sees as a “good-faith effort” to follow through with it.

All of these programs — if and when they come to fruition — are baby steps toward a world in which consumers are able to repair and maintain their devices indefinitely rather than being forced to upgrade every few years. Advocates say there is more each of these companies could be doing to bring about such a future. For instance, they could make parts and repair documentation available for more of their products: Tarizzo said she’d love to see Google expand its new iFixit partnership to include Nest thermostats. Tech companies could also come out vocally in favor of the right to repair at Congressional hearings and when submitting public comments to agencies, and distance themselves from anti-repair lobbying efforts.

Even industry leaders like Dell, which designs some of the most fixable devices out there in addition to regularly publishing repair manuals for, is still a member of trade groups that lobby against repair-friendly legislation, like TechNet and the Consumer Technology Association. If companies that lead on repairability within their own product lines took a more public stand by calling out their own trade groups or industry peers for retrograde positions on repair, Proctor told Grist, that could be game-changing for the industry.

“If we actually want to make a huge change in the sustainability of our electronics, we need leadership,” Proctor said. “We need companies pushing the boundaries of what can be done.”