A 67-mile highway looping around the eastern side of Cincinnati. A widening of Interstate 45 in Houston. A 52-mile, four-lane highway from southwest to central Indiana. The addition of high-occupancy toll lanes on Maryland’s Interstate 270.

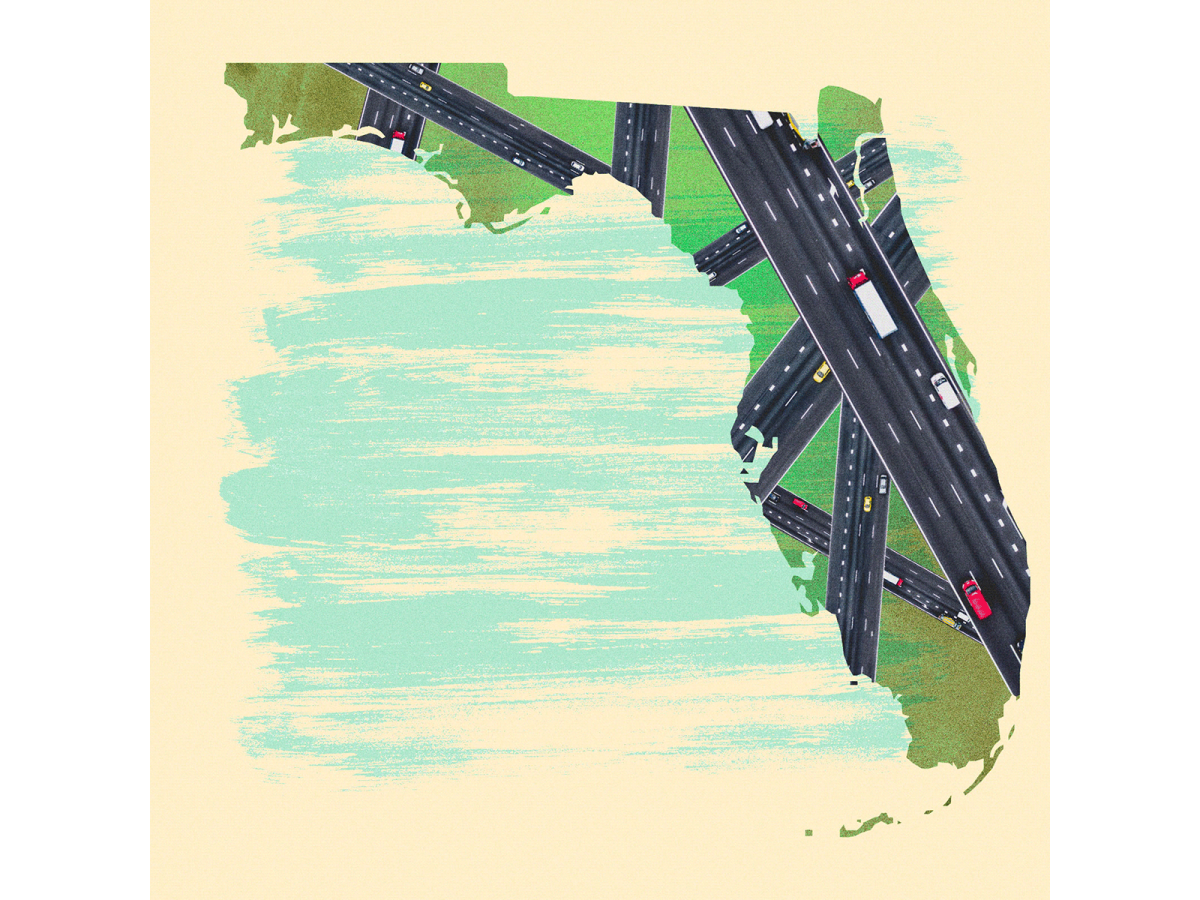

Highway construction and expansion projects are in the works around the country. But none will add more highway miles or be more costly than Florida’s Multi-use Corridors of Regional Economic Significance program, or M-CORES for short. The 330 miles of toll roads are actually three highway proposals, two in north Florida and the other running from central to southwest Florida. The roads, supporters hope, will help the state keep up with its explosive population growth.

But a diverse cross section of opponents have dubbed them the “roads to ruin.” Conservationists worry about the impact on endangered species, especially the Florida panther. Taxpayer watchdogs don’t see the financial sense in the multi-billion-dollar price tag. Young people believe state leaders are forsaking their future by incentivizing driving and sprawl at a time when climate change demands reductions in both. And rural communities in the highways’ paths fear drastic disruptions to their lifestyle and economy.

“What is the return for us?” said Scott Osteen, a farmer living in the proposed path of M-CORES. “You’re asking us to give up land, you’re asking us to give up our current way of life, but currently I don’t see the upside to it.”

Osteen lives in Levy County, which hugs the Gulf Coast near the panhandle. It’s home to about 40,000 people and a diverse economy, with watermelon and peanut growers, ranchers, timber production, and burgeoning clam businesses on the coast. Although the exact routes haven’t been chosen yet, Levy County could host two of M-CORES’ three highways — the Northern Turnpike and Suncoast Connectors — within a decade. In front yards across the county, residents have staked signs opposing the toll roads.

Osteen grows a little bit of everything — peas, turnips, squash — and raises chickens, pigs, and turkeys on the farm his grandfather bought a century ago. He and other community members are concerned a highway will tarnish their county’s beauty and disrupt the region’s agricultural industry. They’re also worried about what highways bring with them.

“It’s the impact of increased traffic, the impact of being a drive-through community, if you will, where these larger suburban, urban areas are driving through us to get to another larger city,” Osteen told Grist. “At best, they stop and get some gas and they’re gone.”

M-CORES was the priority project of former state Senate President Bill Galvano. The Republican from the west coast of Florida did not represent one of the counties in the potential path of the project. But he thinks it‘s essential to accommodate the state’s population growth and relieve congestion on Interstate 75, which runs through his hometown of Bradenton on the west coast. Florida expects to add at least 6 million residents by 2045.

The former state Senate president has also argued that the roads would create more hurricane evacuation routes and more lanes for logistics and trade — a boon for the state’s economy. The Florida Chamber of Commerce and the car and truck industry are among M-CORES’ most enthusiastic supporters. Head of the Florida Trucking Association Ken Armstrong says his industry loses billions of dollars because of traffic congestion.

The 2019 legislation that created the M-CORES program within the Florida Department of Transportation requires construction to begin by the end of 2022 and highways to be open to traffic by 2030. Before the legislation passed, the agency hadn’t included these roads in its list of planning priorities. Critics say that proves M-CORES is a political project rather than necessity based. Vivian Young, the communications director for 1000 Friends of Florida, a nonprofit advocacy group that focuses on growth management and planning, says the legislative approach to approving these roads has undercut FDOT’s planning process, since the agency did not request these highways.

“DOT was basically given marching orders to go ahead with a 330-mile toll road corridor,” Young told Grist.

The M-CORES legislation diverts general revenue funds collected from a portion of vehicle license taxes to the State Transportation Trust Fund and also redirects turnpike revenue to build the project. The state has allocated $760 million to it through 2024. The rest of M-CORES’ funding would come from two major transportation bond programs. Estimates for the entire project run as high as $26 billion, based on the construction of other highways in the state.

In a year when lawmakers must reckon with the pandemic’s budget impact, the price tag for M-CORES is difficult for some critics to swallow. The conservative think tank Florida TaxWatch released an analysis in 2020 of the Suncoast Connector section of M-CORES, a 150-mile stretch running from Citrus County to Jefferson County at the Georgia border. It wasn’t flattering. Florida TaxWatch estimates it could cost between $4 billion and $10.5 billion to build just this section. At its highest price tag, the route would have to approach the usage of the state’s most heavily trafficked toll road in South Florida to cover the bond costs.

“The uncertainty created by COVID-19 makes investing in major transportation projects that Floridians will be paying off for more than 30 years even riskier,” the report says.

And then there are the environmental costs of the project. The transportation sector is the largest source of greenhouse gases in the U.S., making up 28 percent of emissions. Oscar Psychas, founder of the Young Leaders for Wild Florida, says highways invite more cars onto the road, a well documented phenomenon known as “induced demand.” Those cars emit carbon dioxide, driving climate change in a state that’s among the most vulnerable to its effects. Without proper protections for the environment, the roads could also bring more urban sprawl — which leads to yet more driving — and disturb some of the state’s natural barriers against sea level rise, such as wetlands. The southwestern leg of the highway could slice through some of the last remaining habitat of the endangered Florida panther.

Psychas says young Floridians are the ones who will face the consequences of M-CORES. “Our future, in a way that I don’t even think is sufficiently recognized in the public realm, is being so sold out,” Psychas told Grist.

Concerns about induced demand and transportation emissions dog many of the highway projects being planned around the country. In Houston, opponents of widening Interstate 45 have argued that it runs counter to the city’s targeted climate goals, which include a 20 percent reduction in vehicles miles traveled by 2050. (The Biden administration recently pressed pause on this project under the Civil Rights Act due to its impact on communities of color in Houston.) Cincinnati has similar goals. Opponents to highways in other parts of the country, like Indiana, are simply concerned about the environmental impacts on largely untouched land.

FDOT cautions that M-CORES is still evaluating each potential corridor for the project. In an emailed statement to Grist, agency spokesperson Natalie McElwee said it will conduct financial and environmental feasibility studies when the agency chooses the most suitable path. A “no-build” option remains on the table.

The project’s opponents are doing all that they can to make that option a reality. Young Leaders for Wild Florida has joined more than 100 other groups in a coalition called No Roads to Ruin. The coalition has kept up a steady letter-writing campaign to newspapers and rallied at the state Capitol in protest. The group also analyzed nearly 10,000 public comments that FDOT task forces received about the project and found that 93 percent were negative — suggesting that there is little constituency for M-CORES. “Our work must continue until the state abandons all proposals to build new unnecessary and damaging roads in the M-CORES study area,” Ryan Smart, executive director of the Florida Springs Council and a member of the coalition’s steering committee, said in a statement to Grist.

There’s evidence that community leaders are listening to M-CORES’ opponents. The Levy County Commission has adopted a resolution opposing the construction of the Suncoast Connector. The Gilchrist and Jefferson county commissions have done the same.

The issue has also come back to the state legislature. One measure to nix the toll road program has cleared the state Senate although the No Roads to Ruin coalition is concerned because this measure would allow FDOT to continue evaluating the usefulness of the northern toll road projects.

Separate legislation from state Senator Tina Polsky and state Representative Ben Diamond would repeal M-CORES and redirect funds for it back to general revenue. They say the program is draining FDOT’s attention. In a virtual press conference introducing the bill in February, Diamond, based in St. Petersburg, said the agency has pushed one highway project in his district back two years because of a lack of revenue.

Lindsay Cross, government relations director for Florida Conservation Voters — a steering member of the No Roads to Ruin coalition — also spoke at the press conference. She said the toll roads would harm the state’s top two industries: tourism and agriculture. “Both of these economic drivers rely and depend on clean water, protected lands and wildlife, and smart development, but these things are at stake if we don’t repeal M-CORES,” said Cross. “Our water, our natural places, and our wildlife are core to our identity as a state, and we must protect them.”