Chris Laderer was 34 days into his tenure as chief of the volunteer fire department in Darlington, Pennsylvania, when the station received a call that a train had caught fire in the neighboring town of East Palestine, just over the state border in Ohio. Laderer assumed that an engine had overheated, but as the crew pulled out of the station he saw signs of something far more disastrous.

“We could see the glow and plume of smoke from our station, and we’re 4 miles from the scene,” he recalled. “We realized we’re getting something much bigger than what we anticipated.”

When Laderer’s team arrived, alongside the fire departments from roughly 80 other towns across Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, they found 38 cars of a 150-car train splayed along the tracks, with some emitting flames that smelled, as Laderer described it, of burning plastic. They would learn in the days that followed that 11 cars contained hazardous chemicals, including the highly toxic compounds vinyl chloride and butyl acrylate, which are used in the manufacturing of common plastics.

By Monday, three days after the February 3 derailment, the Norfolk Southern railroad company had sent in their own officials and contractors to perform a controlled burn-off of the vinyl chloride. The tactic was meant to prevent, as much as possible, more than 100,000 gallons of vinyl chloride from evaporating into the air and seeping into the soil and creek beds surrounding the train, although an as-yet-unknown quantity of it already had. (“Either we were going to blow it up, or it blows up itself,” Trent Conaway, the mayor of East Palestine, explained at a town hall the next week by way of illustrating a frustrating lack of options.)

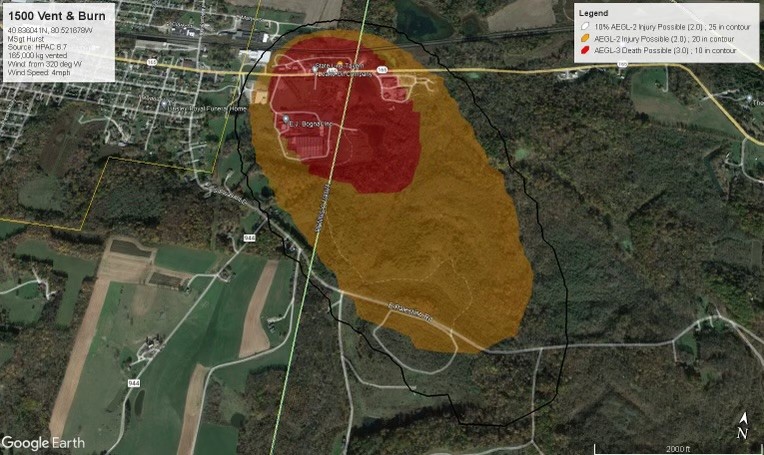

But the burn didn’t go quite as planned. A towering, bulbous cloud of black smoke erupted from the train in the explosion and then spread over the surrounding area like a pool of oil, where it hung in the low atmosphere for hours and hours. Experts have attributed the smoke’s stubborn refusal to dissipate to a weather phenomenon called an inversion, where warm air that rises into the atmosphere after a sunny day traps the cold air coming off the ground as night falls. “The smoke that was supposed to stay up started banking down a bit on the area,” Laderer explained.

Jeremy Woods, a mechanic for the Darlington-based trucking company and repair shop Lync, described the scent that permeated the air all of Monday night as that of charred PVC pipe, but with a hint of chlorine that reminded him of the YMCA pool. Trisha Blinkiewicz, whose home sits about 4 miles east of the derailment, went to dinner in nearby Chippewa, Pennsylvania, on that same Monday evening. She found the town buried in a low-lying fog that felt thick on the skin, with a distinct, abrasive smell of burnt plastic.

The train that crashed in East Palestine derailed about 20 miles northeast of its destination of Conway, Pennsylvania, one of the industrial towns and small cities that line the Ohio River as it flows west from its mouth in Pittsburgh. The Upper Ohio River Valley — which stretches, roughly speaking, from that mouth down to where West Virginia meets the tip of Kentucky — has been the site of proliferating petrochemical development over the past decade, as oil and gas companies turn their attention away from fuel and toward a much richer prospect: plastics.

Ethane gas fracked from the Marcellus Shale, which extends across Pennsylvania into the eastern edge of Ohio and northern West Virginia, can be “cracked” into ethylene, a flammable gas critical to the production of plastics used for packaging, bottles, and electrical insulation, among other products. And all of the infrastructure that is required for every step of plastic production and transport — wells, pipelines, refineries, ports, plants — has spread like a spider’s web over the region.

The accelerating petrochemical development is simply the newest incarnation of industrial exploitation for a region that has been plagued by legacy pollution since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. The pressing question is whether the people who have lived here for generations have hit their breaking point, and whether they feel empowered to demand more from the corporations that threaten their homes and the politicians that enable them.

“Honestly, I never expected this big an incident to happen in my entire life, let alone my first month as fire chief,” said Laderer. “And Norfolk Southern are not telling us a lot, and they’ve got me questioning things.”

The unique Appalachian topography of the greater Ohio Valley tends to fortify the pollution created within it, as if the geology that had endowed the region with such bountiful fossil fuel and mineral reserves also cursed it to suffer more for them. Major industrial facilities and railroad hubs are usually established on the river, for ease of both transportation and waste disposal, and the emissions that they produce get trapped by the steep hillsides that frame the tributaries.

Many houses in the rural community of Enon Valley, Pennsylvania sit just a few feet from the railroad tracks. Grist / Eve Andrews

Left: A decommissioned train sits behind the Greersburg Tavern in Darlington, Pennsylvania. Right: A sign in East Palestine, Ohio, expresses hope for the future. Grist / Eve Andrews

The Shell cracker plant, which began operations in the fall of 2022, is a sprawling behemoth on the edge of the Ohio River in Monaca, Pennsylvania, directly across the river from the derailed train’s destination in Conway. The plant, which is widely considered to be a grim arbiter of future petrochemical development in the region, takes locally fracked gas and breaks it down at a molecular level to manufacture the ethylene “nurdles” — translucent plastic pellets the size of a grain of arborio rice — that make up many household and single-use plastics.

Residents of eastern Beaver County, which is quite rural, say that they have not personally felt the adverse effects of the Shell plant. They do not smell chemicals in the air or see nurdles floating in the creeks near their homes, unlike those who live downstream of the plant. They are more or less protected by the same topography that traps pollution around the facilities that create it, with a buffer of hills and hollers that rise and fall between their communities and the plant itself. But the derailment in East Palestine on February 3 brought the more disastrous consequences of plastic production far closer to home.

Ron Stidmon moved from New York City to Enon Valley, Pennsylvania, in 2003, seeking stillness and solitude after having lost several friends in the 9/11 attacks. Enon Valley, which sits a few miles northeast of East Palestine on the border between Beaver and Lawrence counties, is secluded and quiet, dotted with both Amish farms and sprawling properties. Stidmon bought a farm, unsuccessfully tried to make a lot of different crops work, and finally cracked the code of profitability with garlic. He has steadfastly committed to organic practices on his land for 20 years, to the extent where he grumbles when a neighbor burns a tire on an adjacent property.

When Norfolk Southern performed the controlled burn-off of vinyl chloride on February 6, Stidmon recalled, “it looked like the end of the world with the smoke coming up.” He’s now watching the wells and ponds on his property daily, with no other option than to simply wait for testing to learn if carcinogenic chemicals from the derailment have leached into the aquifer. He’s optimistic that his water supply will be spared of contamination, simply because he’s upstream of the crash.

“If we were a mile or so west, it would be completely different. If the winds had been blowing a different direction, it would have been different,” he said. “It’s a matter of luck — has nothing to do with having a plan, or setting up that we’re safe.”

Stidmon had been anticipating a disaster like this for years. In 2016, he was on the Darlington Township’s Board of Supervisors, where he began to raise the issue of railroad safety. He was concerned by the sheer volume and frequency of trains routed along the track that wraps around Darlington, running north through the village of New Galilee, east across Enon Valley, and over the state border into East Palestine. According to Stidmon, he spent a year trying to get Norfolk Southern to simply provide the number of trains that came through in a day. When months went by and the company never answered, he and a few neighbors got together to stay up for 24-hour shifts, watch the tracks, and count. The figure at which they arrived was 60.

“[Norfolk Southern] won’t do anything to address the people’s concerns, to address legitimate problems. They have such a cavalier attitude: ‘This is our track, our business.’ It’s discomfiting to know that anything can happen, with practically no repercussions,” said Stidmon. “You can live your own life as clean as you want, but these guys can destroy everything you’ve done to keep it clean for yourself.”

Jason Blinkiewicz owns the trucking company and repair shop Lync, which is located a little over a mile from the derailment. He lives in Enon Valley, where the railroad runs right in front of his house. (On the night of February 3, he and his wife, Trisha, found that the engine of the train that had crashed had “cut and boogied” to come sit on the tracks in their front yard.) He, like most of his neighbors and employees, doesn’t trust Norfolk Southern and assurances from the Environmental Protection Agency that the air and water have been safe to breathe and drink. The borough of Enon Valley commissioned independent testing of wells and streams, and the community is awaiting results.

“It’s normalized to some degree because there’s already low air quality in the area,” Blinkiewicz said. “The cracker plant is putting out volatile organic compounds, or what’s the nuclear power plant doing, or how about the coal plant right behind it that they shut down not that long ago? What about the mills in Midland and the steel plant in Koppel?”

But all of those facilities are far enough from Blinkiewicz’s home and workplace that he hasn’t felt their impacts nearly as acutely as those of the derailment. “I think it’s the first time, in my 46 years on this planet, in this area, that it gives you an uneasy feeling about everything,” he said.

“And as much as it pains me to say, my trust has to lie in our government. Which is hard to do, right? But we have to rely on those government agencies to protect us. That’s what they’re there for.”

On the night of February 15, East Palestine hosted a town hall at the local high school for residents to ask questions of both state and federal EPA officials. (Representatives from Norfolk Southern pulled out hours before the meeting due to “the growing physical threat” to their employees’ safety. Those threats have not been substantiated.) Volunteers with the East Liverpool, Ohio-based community group River Valley Organizing, were standing outside of the high school’s front door passing out flyers for the group’s own town hall to take place the following week.

Amanda Kiger, director of the group, is familiar with the pervasive distrust of government, regardless of political orientation, in the Ohio Valley region. It is hard to have faith in one’s representatives with a centuries-long legacy of politicians whose loyalties have been bought by industry.

“Historical pollution has been just layered on this region for so long,” Kiger said several days later in an interview. Stoneware potteries, coal mines, and steel mills mostly died off to be replaced by refineries, hazardous waste incinerators, unconventional gas wells, and petrochemical facilities. “And when you look at communities that are environmentally devastated, bad and polluting commerce attracts more bad and polluting commerce. They can go: ‘We didn’t do that, they did that, that’s been there for years.’”

Two days before the town meeting, a week after the black cloud of burning vinyl chloride spread over East Palestine and its neighboring towns, residents around the Shell cracker plant about 20 miles southeast started to post reports of a large flame emitting from it.

The flame was evidence of a “flare,” which is a mechanism meant to regulate malfunctioning of the plant’s machinery by expelling excess hydrocarbons into the air. This flaring, while preventing a more disastrous outcome for the plant and its surroundings, pumps volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into the atmosphere. In just a few short months since being operational, Shell has already exceeded its annual allowance of VOC emissions as permitted under the Clean Air Act and the Pennsylvania Air Pollution Control Act. That’s in spite of the fact that the facility has the second-highest permit for VOC emissions in the state. In fact, the environmental organizations Clean Air Council and Environmental Integrity Project intend to sue Shell for the plant’s early violations.

Due to bureaucratic delays from both Shell (which is required to notify the community of flaring activity) and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, it can sometimes take as long as a month for residents of Monaca and the surrounding towns to learn that a plant malfunction happened. But the resident groups Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community (BCMAC) and Eyes on Shell have asked local “watchdogs” to post whether they’ve observed a flare or felt changes in the scent or feel of the air around the plant.

Anaïs Peterson, a volunteer with Eyes on Shell, notes that in the months prior to the Shell plant’s official opening in November, the group of concerned citizens that she helped convene would see about 40 attendees at their monthly meetings. By January of this year, several months and multiple flaring events into the plant’s operations, that number had tripled.

“Sometimes the bad things that happen in the community are the moments you can bring folks together,” said Kiger. “And it takes the community coming together to push back on federal and state legislators.

“But am I really sick and tired that my community is the casualty, and we have to be the message-bringers? Absolutely. It’s getting overwhelming.”

On the evening of February 23, dozens of residents from within several miles’ radius of East Palestine crowded into a small storefront on the town’s commercial thoroughfare for River Valley Organizing’s town hall event, spilling out of the main room into the lobby and kitchen. A panel of independent experts in environmental cleanup and hazardous chemicals answered questions from the community. The atmosphere darkened as those in the room processed new information: that the EPA had not been testing air, water, or soil samples for dioxins, potential toxic byproducts of the vinyl chloride explosion that can persist in land and sediment for decades without proper cleanup.

As the evening went on, the questions grew more distressed: When I go home tonight, what is the first thing I can do to make sure the air is clean for my children to breathe? How can I protect my livestock and pets that roam land that might be contaminated with dioxins? Is my home ruined forever? And, above all: How do we make sure Norfolk Southern sees justice for what they’ve done to us?

“You would have tripped over your own shoes without a flashlight, the smoke was so thick — like being in a cave,” said one resident of New Springfield, Ohio, a few miles northwest of the derailment, who expressed concern to the experts assembled that he couldn’t safely grow produce and raise livestock on the land that had been contaminated by that smoke. “We’ve been pretty self-sufficient, and now we’re zero self-sufficient. What do you pay property taxes on 40 acres for if you can’t grow a tomato?”

One of the great, enduring appeals of rural American life is the dream of complete independence. You buy property, build a homestead, grow food, raise your family. Your children play in the creek in the summer and ride sleds down sloping white hills in the winter. But when one powerful corporation’s mishap puts all of that at risk, it becomes clear that a so-called independent existence is only protected through the strength of community.

“I don’t care if you’re red or blue, I don’t care if I beat you up in the bar 10 years ago,” said Jamie Cozza, an organizer for River Valley Organizing and lifelong resident of East Palestine, before urging those gathered to contact every elected official in the region. “We need to come together right now and use our voices, because no one else is going to fight for us.”