A couple of years ago, banning the construction of new gas stations anywhere in the United States would have seemed like a far-fetched idea. But it could soon become a political reality, not in a public transit dreamland, but in the sprawling, car-centric city of Los Angeles.

Last March, the town of Petaluma, California, became the first town in the country to prohibit new gas stations, following through on its declaration of a “climate emergency” in 2019. Other small towns in Sonoma County, like Rohnert Park and Sebastopol, have followed Petaluma’s lead. The effort has since expanded beyond California, with policies to prevent new gas stations being developed in the Comox Valley district in British Columbia as well as in Bethlehem, New York.

If Los Angeles institutes a ban, it would be the first major city to do so. At a press call arranged by the nonprofit Stand.Earth on Wednesday, Andy Shrader, who advises city councilmember Paul Koretz on environmental issues, said that Koretz plans to introduce a policy to end the permitting of new gas stations. “We’re keen on getting it done before the end of this year,” Shrader said.

“Our great and influential city, which grew up around the automobile, is the perfect place to figure out how to move off the gas-powered car,” Koretz said in a statement.

While the idea might sound controversial on the surface, the bans that have been approved so far only stop the construction of proposed gas stations, meaning that there will still be plenty of places left for Americans to fill up their cars. The United States has one gas station for every 2,500 people — more than twice the number of gas stations per person than the European Union.

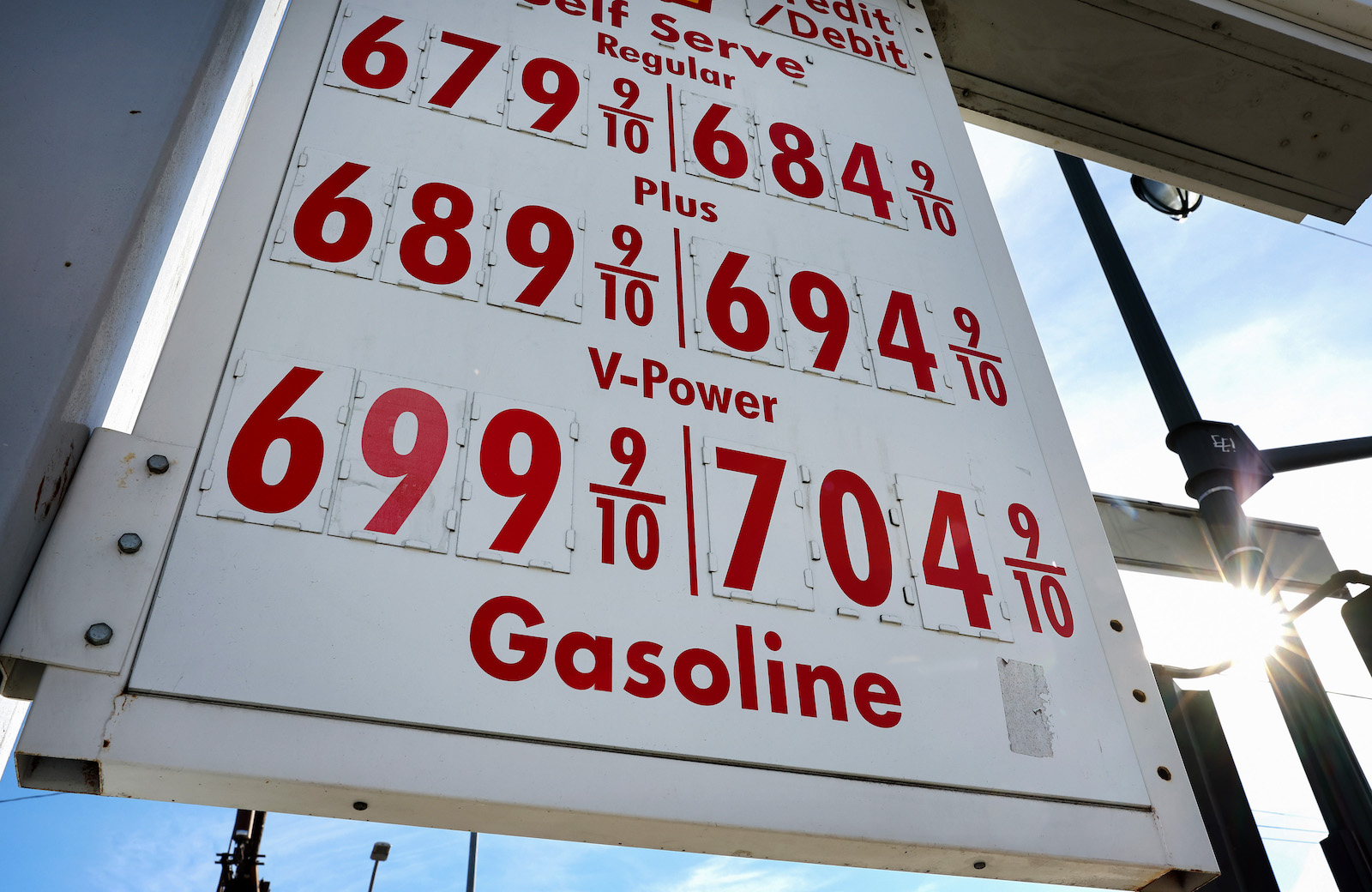

Gas prices have soared to an average of $6.37 in California, the highest price in the country. But the local bans aren’t expected to have an effect on the cost of gasoline. “Prohibiting construction of new gas stations is not going to do anything to impact gas prices right now,” said Anne Pernick, who works to help communities to shift away from fossil fuels with the nonprofit Stand.Earth, at the press call. “But the cost of new gas stations in terms of the health, equity, and safety of the community, as well as future stranded assets, is a bill that definitely ends up being paid by public dollars.”

Proponents of the policy say that the destructive wildfires, killer heat waves, and heavy flooding that have hit the U.S. recently, fueled by climate change, are a sign that it’s time to stop expanding fossil fuel infrastructure. They also point out that gas stations can cause lasting health effects, releasing benzene — a known carcinogen — and contaminating the air, water, and soil. Shuttered gas stations make up half of the country’s 450,000 contaminated brownfield sites, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. That number is sure to grow as electric vehicles take over the road in the coming years, cutting the demand for gasoline.

Local officials working to stop the construction of gas stations argue that gasoline will soon become a thing of the past. California is planning to phase out the sale of gas-powered cars by 2035, with other states following or aiming for even stricter deadlines. President Joe Biden plans to build out infrastructure for electric vehicles, installing half a million chargers around the country by 2030. At the same time, the auto industry has quickly pivoted to making electric vehicles, perhaps inspired by watching Tesla become one of the most valuable companies on earth.

Economic considerations have also been key for the towns that want to stop new gas stations. As much as 80 percent of service stations may be unprofitable by 2035, according to calculations from the Boston Consulting Group. Putting the whole picture together, “you just see there’s no future for gas stations,” Pernick said at the call on Wednesday. The costs of cleaning up abandoned gas stations, she said, will be borne by taxpayers.

While the ban might face headwinds at the state and federal levels, Shrader says that it’s a common-sense solution that towns and cities can adopt now.

“It’s really up to cities to turn around climate change,” he said at the press call. “If you have lung cancer, you stop smoking. If your planet’s on fire, you stop pouring gasoline on it.”