Buick City parking lot, 2010.Photos: Wes Janz, except when notedCross-posted from Places [at] Design Observer, an online journal of architecture, landscape and urbanism, published in partnership with Design Observer.

Buick City parking lot, 2010.Photos: Wes Janz, except when notedCross-posted from Places [at] Design Observer, an online journal of architecture, landscape and urbanism, published in partnership with Design Observer.

“Distressed are big chunks of Detroit, Flint, Gary, Chicago, East St. Louis, and Cincinnati.” This is what I wrote after completing the weeklong Midwess Distress Tour with my Ball State colleague Olon Dotson and a dozen architecture students in October 2006. “Depressed. Dysfunctioned. Disoriented. Devolved. Dissed. Dissing. How many abandoned buildings should I photograph and take others to photograph before we get the picture? How many houses do you have to see being torn from a city’s fabric before the tearing of one life from another no longer registers? When should you stop, or start, caring?”

After “Midwess,” I saved an email that Glenn Johnson, a property manager at a local land bank who led our tour of Flint, wrote to one student: “I was born here. I would never leave here for good. All that it is and all that it isn’t,” Glenn wrote, “Flint, Michigan, will always be home to me.”

Flint is a city I return to, its deep decline and the determination I find among its residents haunting me, challenging me. We did a second weeklong driving tour in October 2008 — again with Olon, and with planning professor Nihal Perera and a group of students — to Cleveland and Youngstown, Ohio; Braddock, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Scranton, and Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania; and Camden, New Jersey. This tour, the Distress Too Tour, along with estimates of 10,000 to 12,000 abandoned houses in my home city of Indianapolis, led to more questions. I became convinced that the pain of the Rust Belt has got to be understood, especially by today’s students, by our future architects and designers. This world of central city abandonment, institutional racism, intransigent poverty, unending decline of the physical infrastructure — this is a world they need to know, to come to grips with and maybe get involved with as citizens and as architects. That meant that I had to get involved, had to dig deeper into one place to give dimension and depth to my curiosity. I needed to know more about Flint and its people.

Flint is where the American automaker General Motors was founded in 1908. The city grew as a company town, with several generations of workers and families benefitting from the coast to coast appetite for automobiles that followed both World Wars. Forty years ago, Flint was still home to 190,000 people, with 80,000 locals employed in GM plants. When community leaders imagined the future, they did so with confidence, envisioniong a Flint, their “Vehicle City,” with 250,000 residents. This was, this would be, a place that mattered.

Buick City, 1913.Photo: Michigan Radio Picture ProjectFlint is shrinking. Over time, the hubris of the Big Three, of GM, Ford, and Chrysler — evident in the declines in product quality, the inroads made by foreign auto manufacturers and the assaults targeted at unions nationwide — brought down the U.S. auto industry and buckled the day-to-day routines, expectations, and dreams of all Flintians. Between the years following WWII and today, GM eliminated 70,000 local jobs (if not more) and 85,000 people (if not more) moved out. Auto assembly line worker Ben Hamper, in his autobiographical Rivethead: Tales from the Assembly Line, described this decline and his own devolution as a third-generation GM “shoprat” in the ’70s and ’80s. “What this place lacks in ambience it makes up in ambulance,” he wrote.

Buick City, 1913.Photo: Michigan Radio Picture ProjectFlint is shrinking. Over time, the hubris of the Big Three, of GM, Ford, and Chrysler — evident in the declines in product quality, the inroads made by foreign auto manufacturers and the assaults targeted at unions nationwide — brought down the U.S. auto industry and buckled the day-to-day routines, expectations, and dreams of all Flintians. Between the years following WWII and today, GM eliminated 70,000 local jobs (if not more) and 85,000 people (if not more) moved out. Auto assembly line worker Ben Hamper, in his autobiographical Rivethead: Tales from the Assembly Line, described this decline and his own devolution as a third-generation GM “shoprat” in the ’70s and ’80s. “What this place lacks in ambience it makes up in ambulance,” he wrote.

Flint is fading. With the loss of so much of its industrial base, the economic picture for post-industrial Michigan is pitch-dark. There is less and less governmental support for schools, public transportation, family assistance. “We can no longer afford to live outside our means,” said the new mayor in early 2010, and soon enough there were layoffs in the police and fire departments, the closing of fire stations, and a drop-off in garbage pick-up from weekly to biweekly. People are at the brink, ready to act out. On March 25, 2010, the day before the latest rounds of police and firefighter lay-offs were to be announced, nine houses were set on fire. According to a report by WEYI-TV, the fire battallon chief said: “All the fires seem to have been set intentionally. … It also seems very suspicious, since the fires are happening the day before firefighter layoffs. I think they’re trying to make a point and I think they’re going about it in all the wrong ways.”

In this time of declining and sometimes disappearing city budgets, it’s likely that the difficult decisions being made in Michigan today are coming soon to a city near you. Want to see a preview? Put Flint on your bucket list.

702 & 706 East Third Street, 2009.Flint is efficient. Scavengers and scrappers watch for opportunity. Aluminum siding is stripped and resold into the formal recycling economy. Aluminum windows, hot water heaters, and furnaces are taken, sometimes in daylight, no problem. Copper pipes too, and new electrical wiring. Well before the agents of the formal economy negotiate foreclosure proceedings, what remains is a carcass that was once a home but soon is less than a house. And it’s not just abandoned buildings that are targeted. On my first trip to Flint, in 2006, I spoke with a community activist on a summer day. She said, “Sorry the building is so hot. Our air conditioner was stolen this week. When I called the cops, they said, ‘If we find yours, we’ll probably find ours.'” The police department’s air conditioner had been lifted that same night.

702 & 706 East Third Street, 2009.Flint is efficient. Scavengers and scrappers watch for opportunity. Aluminum siding is stripped and resold into the formal recycling economy. Aluminum windows, hot water heaters, and furnaces are taken, sometimes in daylight, no problem. Copper pipes too, and new electrical wiring. Well before the agents of the formal economy negotiate foreclosure proceedings, what remains is a carcass that was once a home but soon is less than a house. And it’s not just abandoned buildings that are targeted. On my first trip to Flint, in 2006, I spoke with a community activist on a summer day. She said, “Sorry the building is so hot. Our air conditioner was stolen this week. When I called the cops, they said, ‘If we find yours, we’ll probably find ours.'” The police department’s air conditioner had been lifted that same night.

Flint is disappearing. Literally. One understandable but unfortunate dimension of the city’s growth, as pointed out by Robert Beckley, in “Flint Michigan and the Cowboy Economy: Deconstructing Flint,” was the poor quality of much mid-20th-century residential architecture and urban design. Back then, he wrote, “While jobs were plentiful, housing was not and … people were sleeping in tents and cardboard shacks. In response, small poorly constructed housing was quickly erected on narrow lots, close to the factories that provided employment. This building cycle was repeated after WWII.” The houses served their purposes, but most have outlived their life spans. Here’s a reality check: 32 percent of Flint’s residential properties are abandoned, and the average single-family house sells for $16,400. Three to five houses are torn down every working day. The chief of the city’s demolition crew told me that there are approximately 20,000 abandoned buildings.

The good news? The number of house fires per week is down, from 12 to 15 several years ago to 8 to 10 most weeks today. In Flint, that’s one way to measure progress.

A house fire on the front porch leads to demolition, 2006.Flint is elusive. It’s like this for me now, after 20-plus visits: Buildings once there are now gone, replaced by lawns, by weeds, maybe by gardens. Buildings I photographed are now charred rubble or have disappeared. I knew something once, but now it’s changed; or maybe my memories are faulty, maybe I’m at the wrong intersection, expecting to see a building that is a block away. That happens. People I knew have left. They lose jobs, lose interest, lose their way. I lose touch with them. That happens, too. I think I know somebody, and on my next trip to Flint, find out they’ve vanished.

A house fire on the front porch leads to demolition, 2006.Flint is elusive. It’s like this for me now, after 20-plus visits: Buildings once there are now gone, replaced by lawns, by weeds, maybe by gardens. Buildings I photographed are now charred rubble or have disappeared. I knew something once, but now it’s changed; or maybe my memories are faulty, maybe I’m at the wrong intersection, expecting to see a building that is a block away. That happens. People I knew have left. They lose jobs, lose interest, lose their way. I lose touch with them. That happens, too. I think I know somebody, and on my next trip to Flint, find out they’ve vanished.

Flint is without us. Which is to say — influenced by Alan Weisman and his recent book The World Without Us — the question arises: What would Flint be like without people? Weisman writes: “Suppose that the worst has happened. Human extinction is a fait accompli. … Look around you, at today’s world. … Leave it all in place, but extract human beings. Wipe us out, and see what’s left.” The parking lot for the 235-acre Buick City, where thousands of shift workers docked their GM cars, is a prime “without us” site. One of the country’s largest brownfields is being reclaimed by nature, trees grow through cracks in the paving, this will be a great forest, again, if we leave it alone. Next door, the Oak Park playground is overgrown with tall grasses, its swingsets idle. On the site of what was, in my lifetime, one of the world’s most productive assembly lines, the only sounds you hear are the crickets. On every visit to Flint, I think of The World Without Us.

And the idea that there is benefit to this line of thinking — here’s Bill McKibben’s blurb on the front of the book jacket: “This is one of the grandest thought experiments of our time, a tremendous feat of imaginative reporting!” — sounds important, sounds edgy. Weisman and McKibben need to come to Flint. Imagination? There’s no need. Experiment? It’s life in Flint. Grand? Try everyday. Tremendous? Think commonplace. Weisman wrote the book on Flint, he just doesn’t know it.

Oak Park playground, 2010.Flint is an inspiration, at least for some of my students. One group joined me at Ball State’s Virginia Ball Center for Creative Inquiry in Spring 2007, taking a 12-credit seminar-plus-studio titled “One Small Project: Seeking Relevance in the Lives of Leftover People.” Among our experiences: A day in Flint, where we visited the Land Bank, had dinner with local poet-photographer-police officer Brian Willingham (Brian’s books include Thunder Enlightening and Soul of a Black Cop), and watched as two houses were demolished.

Oak Park playground, 2010.Flint is an inspiration, at least for some of my students. One group joined me at Ball State’s Virginia Ball Center for Creative Inquiry in Spring 2007, taking a 12-credit seminar-plus-studio titled “One Small Project: Seeking Relevance in the Lives of Leftover People.” Among our experiences: A day in Flint, where we visited the Land Bank, had dinner with local poet-photographer-police officer Brian Willingham (Brian’s books include Thunder Enlightening and Soul of a Black Cop), and watched as two houses were demolished.

Our main end-of-semester activity was a public show at the Dean Johnson Gallery in downtown Indianapolis. Each student produced an installation; two are worth noting here. In one, Diana rethought the experience of finding a dirty and in-use mattress in a squat set up in an abandoned house. To cover the squatter’s body, she crafted a quilt made from materials found on site. In Diana’s words: “The house was to be torn down and reduced to a pile of scraps … leftovers of this place from which everyone wants out. Scraps, pieces, and piles, all formerly part of a home, that once were part of a bigger idea. My intention was to provide shelter, warmth, and security, constrained by the materials that composed it. By stitching the pieces back together, these scraps can once again create a composition, if only to document the destruction.”

For her project, Katie collected the doors from several houses about to be demolished. She wrote: “A door can be open or closed, either allowing or preventing passage across its threshold. In this same manner, one is allowed or denied access to opportunities throughout one’s lifetime. Pushing through one door may be done with ease, but the next might require much more effort, and even that might not be enough. Closed door after closed door establishes a barrier that one might never overcome. This collection of doors represents numerous barriers, whether it is getting accepted into graduate school, resolving differing cultures, finding a place to sleep for the night, or obtaining a green card. The unbiased character of the barrier makes it universal and therefore unavoidable for people of many backgrounds.”

Top: Katie Petersen, “Hindrance,” Dean Johnson Gallery, Indianapolis, 2007. Bottom left: Diana Short, “Cut and Plugged,” Dean Johnson Gallery Indianapolis, 2007. Bottom right: The author (at right) and architecture students from Ball State University talk with Marvin, a private demolition contractor, on the Midwess Distress Tour, 2006.

Top: Katie Petersen, “Hindrance,” Dean Johnson Gallery, Indianapolis, 2007. Bottom left: Diana Short, “Cut and Plugged,” Dean Johnson Gallery Indianapolis, 2007. Bottom right: The author (at right) and architecture students from Ball State University talk with Marvin, a private demolition contractor, on the Midwess Distress Tour, 2006.

Flint is a role model. With other cities and regions suffering their own sustained downturns, people are looking to Flint for advice, ideas, and hope. Among the main resources is the Genesee County Land Bank. Founded in 2002, and based in Flint, the Land Bank works to prevent tax foreclosure on area homes and encourages reinvestment in the 6,000 residential, commercial, and industrial properties it manages or has acquired through the foreclosure process. Large-scale programs include Demolition, Housing Renovation and Rental, and Foreclosure Prevention. Smaller initiatives, often inspired by the actions of individual citizens or neighborhoods at the scale of one lot, one homeowner, and very small sums of money (maybe no money) include: Adopt-a-Lot, in which neighbors take over the maintenance of nearby lots; Clean and Green, in which locals convert vacant Land Bank-owned properties into gardens; and the Side Lot Transfer program, by which home owners can purchase vacant Land Bank property adjacent to their lots for less than $75 plus the foreclosure year’s taxes.

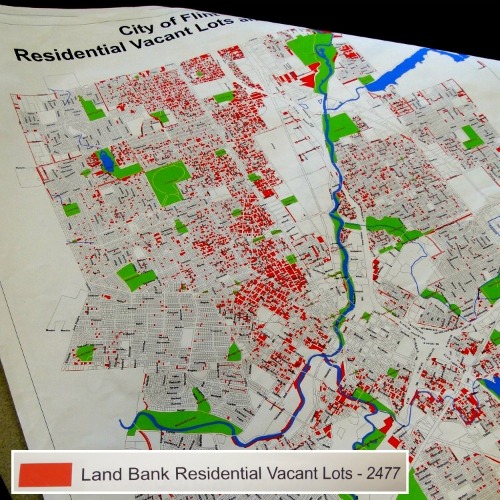

A map of abandoned lots in Flint.Photo: Wayne SenvilleFlint is home, a place that matters not only to academics studying post-industrial urban shrinkage, but also to many people … especially people in Flint. It’s obvious, but not so easy to remember: 110,000 people still live in the city; 5,000 GM jobs remain. I’ve met people who will never leave, a few who have returned. Ties are strong here, multigenerational families stick together. Those who choose to stay speak of their unbreakable ties to the city, of growing up and growing old where they were born. I hear this a lot: “I’ll never leave Flint.” Of all the insights that I’ve gained in the Rust Belt, maybe that one — that people choose to stay — is the strongest and holds the most potential. At least for me. I’ll write about a few of these people.

A map of abandoned lots in Flint.Photo: Wayne SenvilleFlint is home, a place that matters not only to academics studying post-industrial urban shrinkage, but also to many people … especially people in Flint. It’s obvious, but not so easy to remember: 110,000 people still live in the city; 5,000 GM jobs remain. I’ve met people who will never leave, a few who have returned. Ties are strong here, multigenerational families stick together. Those who choose to stay speak of their unbreakable ties to the city, of growing up and growing old where they were born. I hear this a lot: “I’ll never leave Flint.” Of all the insights that I’ve gained in the Rust Belt, maybe that one — that people choose to stay — is the strongest and holds the most potential. At least for me. I’ll write about a few of these people.

Flint is, or was, Keith. I’m not sure where he is now. On one of our early trips with students, we were told that a squatter was being evicted from the front porch of an abandoned house where he had lived for a week. Hung blankets were his walls, the front steps his kitchen. He wasn’t “home,” so we walked on in, stepping around a couch and chair, loaded cardboard boxes, table covered with his belongings, several posters including one that read: “I AM ME … I AM OKAY.” Later I thought: Who the hell did I think I was? Why was I so comfortable walking around, looking at his personal stuff?

Then, suddenly, Keith appeared. We talked. He talked with my students. That day he was moving to another squat a couple of blocks away. He said he had several possible places in mind, was always on the lookout for new places. In some ways, Keith’s city was a network of connected camouflages, small unseen places to make his home, if even for a day or a few weeks. Keith had been squatting for three years, said he knew where to get food and water. He knew “how to hunt.” A student said to me, “Perhaps this is like living in the wild.”

As we departed, Keith said to us: “You can get as much as you want out of life. I believe in being positive.” I didn’t anticipate a pep talk from a squatter. A life lesson.

Keith and his squat on Second Avenue, 2006.Left photo: Mickel Darmawan

Keith and his squat on Second Avenue, 2006.Left photo: Mickel Darmawan

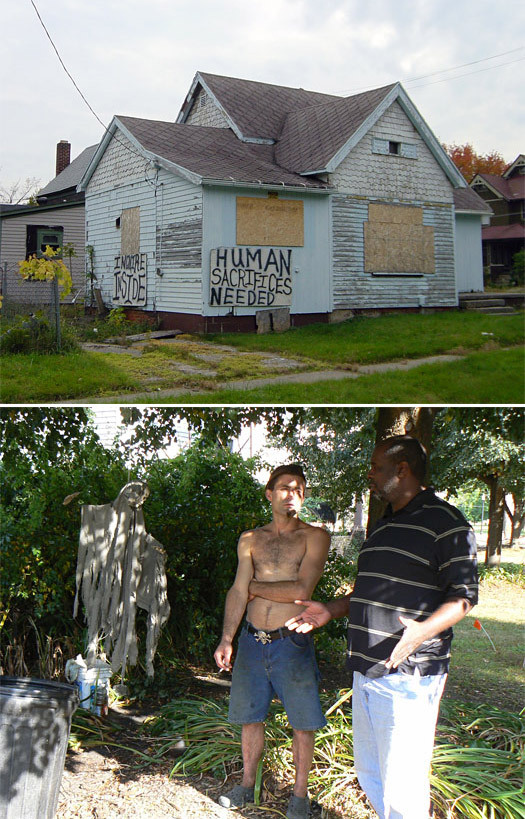

Flint is Adam, living 10 blocks northwest of Keith’s squat in the Carriage Town Historic District, next to in an abandoned house notable for the hand-painted signs hammered to its side:

HUMAN SACRIFICES NEEDED

INQUIRE INSIDE

I’ve photographed the signs, the house, and a backyard adorned with plastic skulls wrapped in barbed wire and plastic skeletons swinging from tall posts. During one snow-swept stop, I heard a bleating goat. Others warned me about the man who lived next to the house, and seemed to be the author of the scary signs: “He took after somebody with a chainsaw.”

Top: Adam’s squat. Bottom: Adam talks with architecture professor Olon Dotson, 2009.On one of my visits, he’s there, Adam. We talk. I’ve got questions, he’s got answers. Skulls and skeletons? They’re gifts, he’s a Halloween baby. Signs? He put them up to discourage others from messing with the house or with him or his stuff. It worked. Other tactics? Using a searchlight to harass hookers, hustlers, meth users, and sellers. Gorilla-gluing a nearby public telephone to stop deals. Filing lawsuits against the city and the hospital nearby for dereliction of responsibility. Expanding into the backyards to the north and south. Chainsaw? Sure, he did walk, not run, after city officials while holding a chainsaw, but it wasn’t turned on and was facing backwards. “Who could possibly be threatened?” Later, when I mentioned Adam at the Land Bank, I’m told that they believe he is a long-term squatter. They can’t find any record of his legal claim to the house and he’s not provided them with one. It’s “his house” to the extent that no one wants it, no one is paying attention, and no one wants to mess with him.

Top: Adam’s squat. Bottom: Adam talks with architecture professor Olon Dotson, 2009.On one of my visits, he’s there, Adam. We talk. I’ve got questions, he’s got answers. Skulls and skeletons? They’re gifts, he’s a Halloween baby. Signs? He put them up to discourage others from messing with the house or with him or his stuff. It worked. Other tactics? Using a searchlight to harass hookers, hustlers, meth users, and sellers. Gorilla-gluing a nearby public telephone to stop deals. Filing lawsuits against the city and the hospital nearby for dereliction of responsibility. Expanding into the backyards to the north and south. Chainsaw? Sure, he did walk, not run, after city officials while holding a chainsaw, but it wasn’t turned on and was facing backwards. “Who could possibly be threatened?” Later, when I mentioned Adam at the Land Bank, I’m told that they believe he is a long-term squatter. They can’t find any record of his legal claim to the house and he’s not provided them with one. It’s “his house” to the extent that no one wants it, no one is paying attention, and no one wants to mess with him.

For nearly everyone (police, zoning officials, prostitutes, the mayor, thieves, newspaper editors), Adam is trouble, unpredictable, and a nuisance. I see that. But I also see Adam as an urban pioneer committed to a place most leave. He’s demanding that the “top” reflect the “bottom,” even as he takes advantages of the gaps between him and them. He’s claimed property no one wants and rides surveillance on a neighborhood even the cops have written off.

Flint is Wendy, leading a meeting of Metawanene Hills Neighborhood Association in the summer of 2006, at a church about one-third of a mile north of Adam’s signs. Wendy, formerly a program officer at a foundation, led the discussion that evening about what to do about the awkwardly shaped traffic island just outside the church. “What was best,” the neighbors asked each other: “Potted or planted landscaping? Geraniums or arborvitaes? Who would organize volunteers? Who had tools? Who might donate plants?” To see the group take on this responsibility was a revelation. It shouldn’t have been. But I say, full disclosure, it was. Four years later, in June 2010, I returned to the area, expecting the worst. You come to expect the worst on the north side, at a crazy-quilt intersection that serves as the forecourt of a “corner store,” a neighborhood grocery where you can buy sugar and fat in all their consumer-friendly forms, along with (reading from the sign) food, wine, and lottery.

But I found a thriving place, planted with irises, junipers, black-eyed Susans, lilies, yaro, coral bells, red leafed Japanese barberry, ornamental grasses, and Russian sage, as the neighbors‘ material and color palette. I found one of the most compelling examples of the privatization of public space that I’ve ever seen. An asphalt place that is a growing place, a piece of connective tissue in a city of many generations, of shared understandings of difficult lives, of lives lost and lives possible.

Traffic islands at the intersection of MLK, Oren, and Welch, 2010.If your eyes and ears and heart are open, Flint changes you. Being encouraged by Keith does that. Questioned by Adam. Pulled in by Wendy and an awkward intersection that blooms year after year after year.

Traffic islands at the intersection of MLK, Oren, and Welch, 2010.If your eyes and ears and heart are open, Flint changes you. Being encouraged by Keith does that. Questioned by Adam. Pulled in by Wendy and an awkward intersection that blooms year after year after year.

It changes what you think needs to be done. What you think you should be doing. What you think of another human being. In time, you might forget the lessons. Insights might fade. That was not and is not the case for me. To say this differently: there is Wes pre-Flint and Wes post-Flint.

Post-Flint, I’m asking: How do we prepare our students for the multiple realities of the world they are about to enter as young professionals and will inherit as global citizens? How might such contemporary issues be introduced to our students? How should architectural education acknowledge the breakdown of the Rust Belt? Is it time to be more engaged not only with the failed policies and falling infrastructures of our shrinking cities, but more importantly, with the remaining residents? I remember, daily, a woman in East St. Louis who said to me: “Professor, we don’t need to be studied. We need help!” How, then, are we to help?

Post-Flint, I’m wondering: What is the place of an architect in a setting where few building permits are issued, where many more buildings are being demolished than designed? What can architects work on if “development,” “next phase,” “expansion,” “anticipated growth,” “better tomorrow,” and “recovery” are stripped from our day-to-day? Or, if the conversations are about developments in scavenger activities, the next phase of federal demolition funding, expansion of landfill holdings, anticipated growth among local salvage yards, a better tomorrow for demolition contractors, or the recovery of urban animal populations? To put this differently, can we shift away from the overwhelming, and suffocating, economic and legalistic frameworks that dominate our profession, our university programs, and our lives?

Post-Flint, I’m searching out “small” initiatives, curious about local progress made by individuals who toil beneath, in spite of, and without knowledge of the larger plans and recovery prospects imagined by trained professionals. I wonder if our work should begin not with development or expansion, not even with a charrette. Might we start with an individual, someone we know on a first name basis? Is this, in a place like Flint, more appropriate? Is this a way, finally, to humanize our profession? To begin with Keith, with Adam, with Wendy? As I move through these moments and ask these questions, I do my best to resolve the contradictions between what I thought was the case, what authorities tell me needs to be done, and what I find. Flint churns as a deepening inconsistency for me, beset by problems, scarred by solutions, and alive with … well … alive with lives.

Flint is. And that’s important to remember.