The United Nations says the ongoing PFAS contamination of the Cape Fear watershed in North Carolina violates residents’ right to a clean and safe environment, and it has urged the Environmental Protection Agency to hold the polluters accountable.

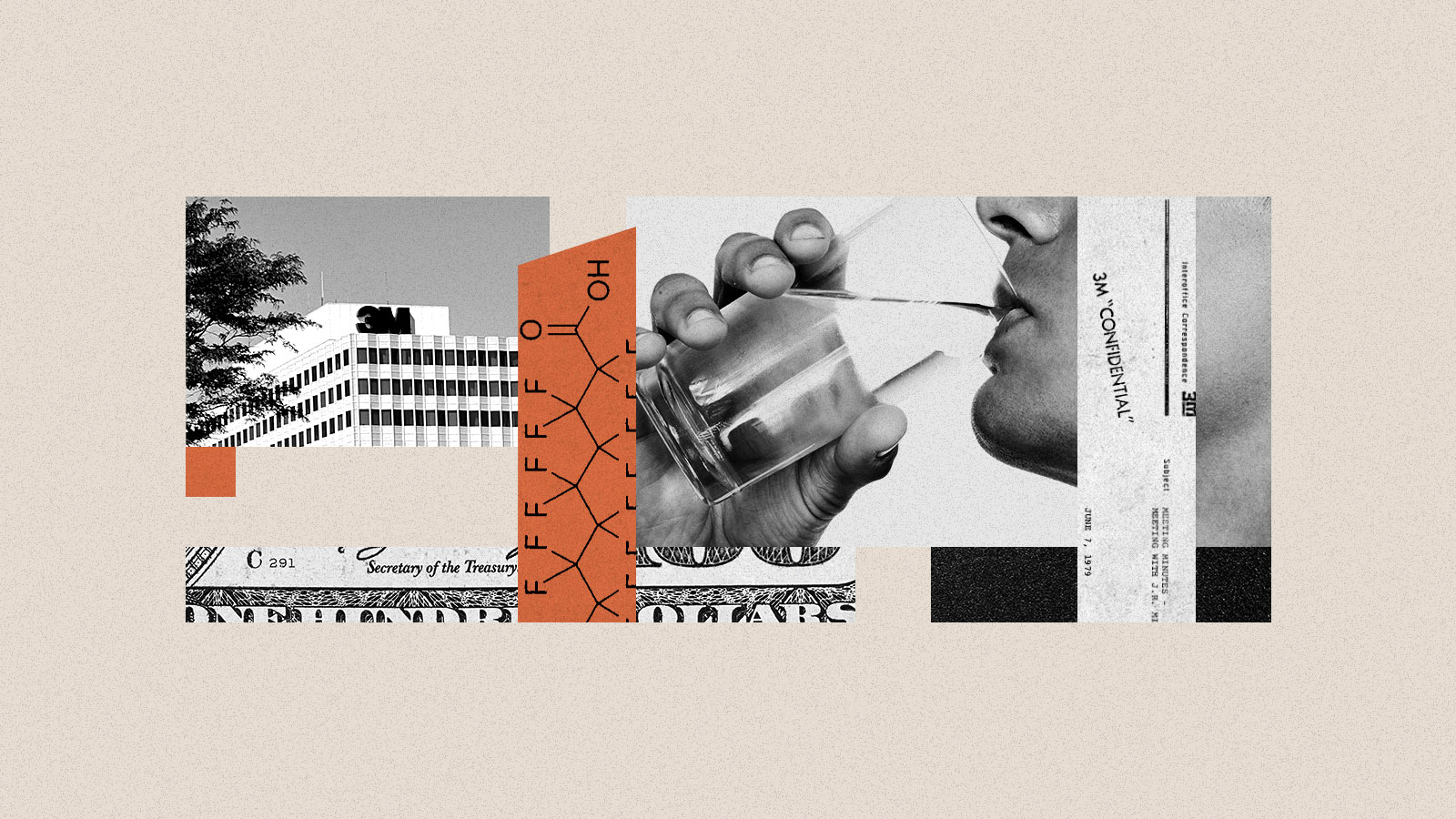

Its declaration marks the first time the international body has used a human rights framework to address the pervasive threat of so-called “forever chemicals” in the United States. That, in turn, could bolster national and international efforts to reckon with the public health and environmental dangers of the 12,000 common compounds classified as PFAS, which do not break down in the environment or in the body.

The Cape Fear River provides water to 1.5 million people, 500,000 of whom live south of the Fayetteville Works chemical plant.* For more than three decades, unbeknownst to residents, the plant, owned first by DuPont and then by the Dutch company Chemours, slowly contaminated the river and local wells with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which are carcinogenic. In 2017, the public, long confused by the commonplace occurrence of rare illnesses, learned who was responsible when a local newspaper broke the story.

In April, a grassroots organization trying to bring Chemours to account wrote a detailed letter to the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Human Rights, asking it to consider the contamination a violation of international human rights law. Over Thanksgiving weekend, Special Rapporteur Marcos Orellana did just that in letters sent to DuPont, Chemours, and Corteva — the three companies associated with Fayetteville Works — and the governments of the United States and the Netherlands.

The letters say the Fayetteville Works plant contaminated more than 100 miles of the river for 40 years and counting, and allege that Chemours knew about the harmful effects of PFAS pollution and likely suppressed that information. The missive to the U.S. government urges the EPA to hold the company accountable, while the document sent to Dutch officials demands an end to the export of PFAS waste to the region. Chemours has been sending such material to the plant for processing and disposal because U.S. laws are more lenient than those in Europe.

Cape Fear residents are relying on the U.N.’s action to bring them some redress after years of fighting for epidemiological studies by the EPA and a shutdown of Fayetteville Works.

“We’re hoping this helps the U.S. government find the political courage it needs,” said Emily Donovan, cofounder of community organizing group Clean Cape Fear. “No one wants to be labeled as harboring a human rights violator.”

In the letter to Chemours, Orellana expressed discomfort and alarm at what he called the company’s long-term disinformation campaigns, which included obfuscating the true danger of PFAS chemicals and proferring them as a climate solution with no peer-reviewed science backing the claim. “In one study,” Orellana wrote in the letter to Chemours, “Certain PFAS were found in 97 percent of local residents tested.” Other peer-reviewed studies cited in the letter linked per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the bloodstream to several forms of cancer, fertility and endocrine disorders, and lung diseases.

The letters follow a series of lawsuits against the same companies over water contamination issues, including one that was recently settled for $110 million in Ohio.

In a statement to Grist and a response to the U.N. letter, Chemours denied wrongdoing, adding that its products are vital to the green transition. “At Chemours, we support science-based regulation, and our remediation activity and emissions control technologies are grounded in the best available science and proven approaches,” said the company. However, it has sought a permit from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality to expand PFAS production, particularly of a chemical called GenX that is particularly difficult to filter out of municipal water systems.

Claudia Polsky, the environmental director of the University of California-Berkeley Law Clinic, helped write the letter seeking U.N. intervention. She said most of the work the companies have done to address the problem has focused on avoiding liability, not controlling emissions. She hopes a human rights framing could pave the way for more sweeping reforms.

“The great thing about framing this accurately as a violation of human rights,” said Polsky, “is that framing is capacious enough to include stories about PFAS health harms, ecological harms, corporate responsibility, about lack of regulatory vigor, about inadequate legal remedies for people who are coming out injured.” It also connects the injustices in North Carolina with similar stories elsewhere in the world, bolstering the case for an international movement to address PFAS as a global problem, and regulate them as a class of chemicals rather than one by one.

The U.N. declaration is the first of its kind in the United States. It is preceded by a similar, though less detailed, action by the U.N. Special Rapporteur in Veneto, Italy, which inspired the residents of Cape Fear to believe they might be able to catch the international body’s attention. PFAS, they say, is a problem with global consequences.

Community members and officials in North Carolina castigated the EPA last month for approving a permit for Chemours to import 4 million additional pounds of GenX PFAS waste from the Netherlands, despite a 2019 EPA order requiring the company to reduce its pollution in the Cape Fear watershed. The EPA put the import on pause after local media uncovered it, causing community outcry. The federal government has not yet responded to the rapporteur’s letter.

Harper Peterson, a former mayor of Wilmington, North Carolina, and state senator for the region, is a founding member of the Clean Cape Fear Coalition. He hopes this international attention will force the EPA to adopt tougher drinking water standards, generate enough public outrage for the state to deny Chemours’ expansion permit, and trigger what he calls much-needed epidemiological studies into the harms of PFAS. The challenge, he said, has been proving to legislators that blowback from their constituents will cost them more than corporate pressure to do nothing.

If the U.S. fails to address the issue, the special rapporteur said, it will be viewed as negligent in ensuring the rights of its own citizens. “We remain preoccupied that these actions infringe on community members’ right to life, right to health, right to a healthy, clean, and sustainable environment, and the right to clean water, among others,” Orellana said in the letter.

*Correction: an earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the whole of the Cape Fear river as providing water to 500,000 people. The river provides water to 1.5 million people in total.