This story was originally published by The Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Arizona, stressed by years of drought, has declared its house-building boom will have to be curbed due to a lack of water, but one of its fastest-growing cities is refusing to give up its relentless march into the desert — even if it requires constructing a pipeline that would bring water across the border from Mexico.

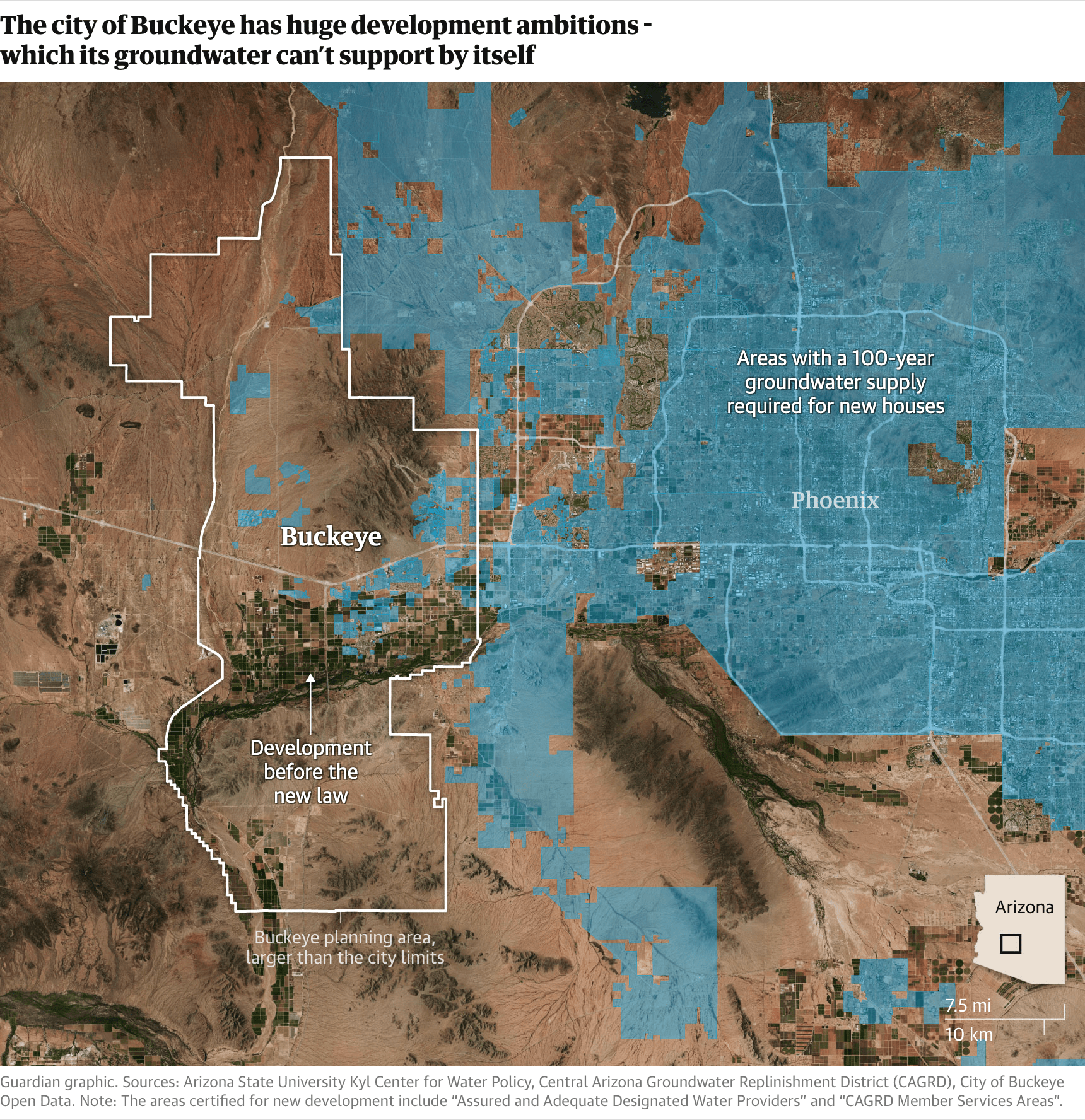

The population of Buckeye, located 35 miles west of Phoenix, has doubled over the past decade to just under 120,000, and it is now priming itself to eventually become one of the largest cities in the U.S. West. The city’s boundaries are vast — covering an area stretching out into the Sonoran Desert that would encompass two New York Cities — and so are its ambitions.

Buckeye expects to one day contain as many as 1.5 million people, rivaling or even surpassing Phoenix — the sixth largest city in the U.S. that uses roughly 2 billion gallons of water a day — by sprawling out the tendrils of suburbia, with its neat lawns, snaking roads, and large homes, into the baking desert.

Arizona’s challenging water situation appears a major barrier to such hopes, however. In June, the state announced that new uses of its groundwater have essentially hit a limit, placing restrictions on house building, just a few months after the state lost a fifth of its water allocation from the ailing Colorado River.

There isn’t enough water beneath Buckeye to support homes not already being built, Arizona’s water department has said. But the city is embarking upon an extraordinary scramble to find water from other sources — by recycling it, purchasing it, or importing it — to maintain the sort of hurtling growth that continues to propel the U.S. West even in an era of climate crisis.

“Personally, my view is that we are still full steam ahead,” said Eric Orsborn, Buckeye’s ebullient mayor. Orsborn said he understands the state has to be “really careful” with water resources but that the city is exploring “options to keep us going and allow us to continue to grow at the rate that we want to grow.”

Some of the grander options are ambitious to the point of appearing outlandish, such as a plan to bring desalinated seawater from Mexico to Arizona via a lengthy, uphill pipeline. Arizona may, instead, pipe in water west from California, or from 1,000 miles east, from the Missouri River. Buckeye has already shown it is prepared to spend big to achieve its dreams — in January the city council agreed to spend $80 million for a single acre of nearby land, an area smaller than a football pitch, just to secure its attached water rights.

“We’ll be as big or larger than Phoenix, ultimately — we don’t have to have all that water solved today,” Orsborn said in city hall, which itself may have to be upsized to deal with Buckeye’s growth. On his office wall is a map of the vast expanse of untouched desert that sits within the city’s voluminous territory.

“What we need to figure out is what’s that next crazy idea that’s out there,” said the mayor, who also owns a construction company. “We’re just hustling to get to that point, to keep things moving along.”

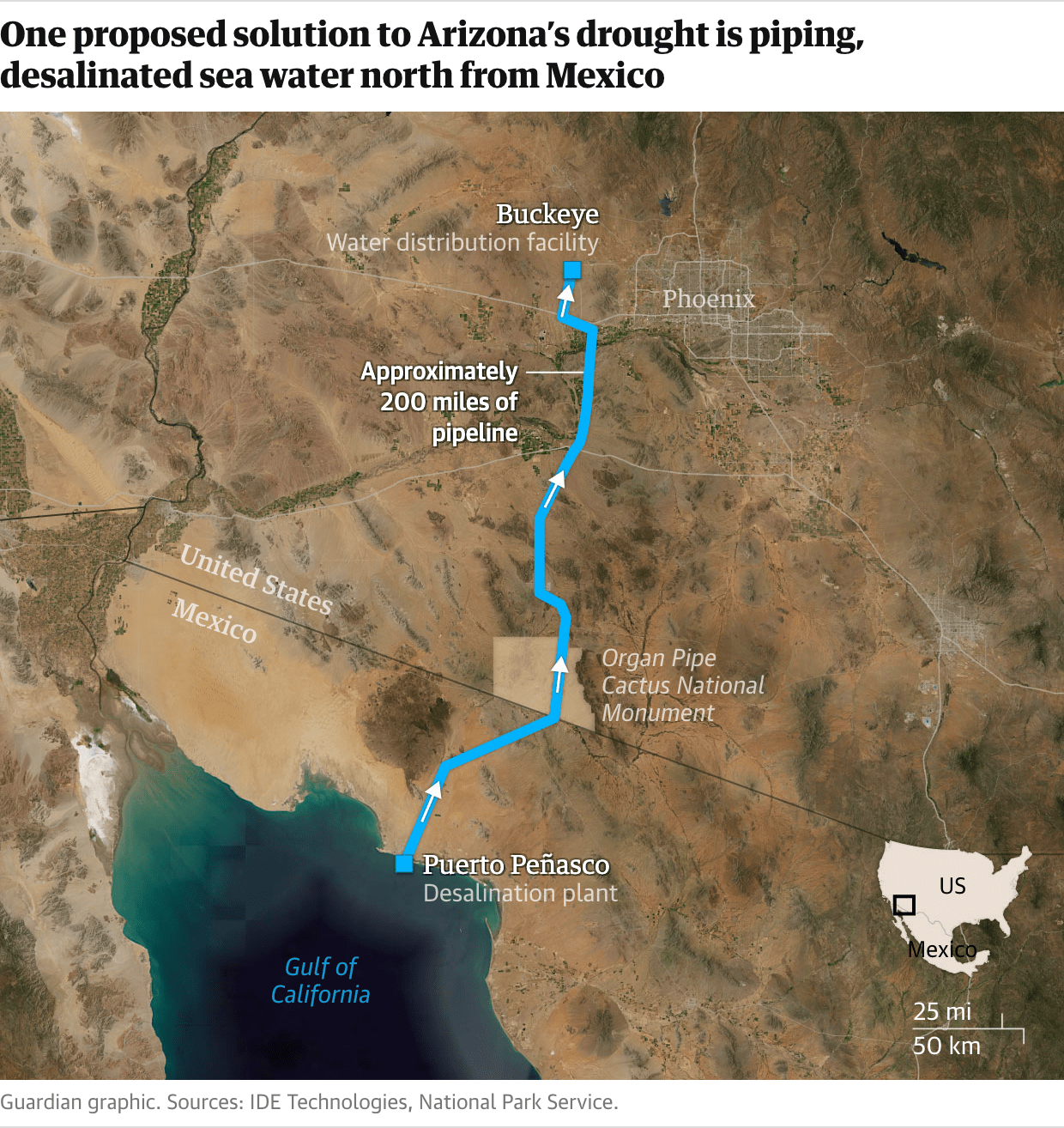

Perhaps the most “crazy” of the ideas is the one that would involve building a desalination plant in the Mexican town of Puerto Peñasco, perched on the edge of the Gulf of California, to suck up seawater and then send the treated water in a pipeline several hundred miles north to Arizona. Much of the pipeline’s proposed route is uphill and will traverse an international border, a federally protected area famed for its cactus and several small towns.

Environmentalists have already criticized the plan for its potential ecological impact upon both land and sea — the salty brine left over would be dumped back into the Gulf of California, altering its composition and potentially harming its marine life. The odds may be against the pipeline, given the cost and opposition. But IDE, the Israeli company that proposed the $5 billion plan, has said the pipeline would be “transformative” for Arizona, would provide enough water for the entire state and “secure Arizona’s future growth.”

Arizona’s Water Infrastructure Finance Authority (or WIFA), the agency tasked with implementing a new inflow of water to the state, is assessing the Mexico idea, as well as other options. Chuck Podolak, director of the agency, has his own office map that helps him envision other possible stupendous infrastructure undertakings, such as a pipeline running from another desalination plant, in California, or a pipeline that could convey water from the distant Missouri River to the thirsty desert.

“Those are big, audacious ideas, but I don’t think any are off the table,” said Podolak. “We’re going to seek the wild ideas and fund the good ones.”

Podolak acknowledged any pipeline from Mexico will face numerous hurdles — Wifa has been in touch with lawmakers in Mexico, some of whom are unfavorable to the idea — but insisted Arizona will continue to push for a new, leviathan project to make up its water shortfall.

“I just want to see multiple projects and figure out the best one for us. If we want to have that long-term security, we do need a new bucket, so to speak, a new source of supply outside of the state. This is a fantastic place to live.”

Podolak points out such big ideas are in keeping with previous monumental, and seemingly impossible, projects. “We dammed up the Colorado River and built the Hoover Dam, we have an artificial river that runs from Lake Havasu to Tucson uphill 300 miles — it’s called the Central Arizona Project,” he said.

“All these things seemed audacious, but now they’re part of the landscape. We’ve been doing it for 100 years.”

Such grandiose plans are being mulled because Arizona faces pressures like never before. The state has been in the teeth of a drought, spurred by global heating, that is the worst the U.S. Southwest has seen in approximately 1,200 years. About a third of the state’s water supply comes from the Colorado River, which has shrunk as temperatures have risen. Last year, under a mechanism where Arizona shares water with other states, its allotment of Colorado River water was cut by 21 percent.

Arizona’s other major water source — from underground aquifers, sucked up by wells — has become depleted in some parts of the state and, in the rapidly growing areas on the fringes of Phoenix, have been entirely laid claim to by developers who have to show under law that there is a reliable 100-year supply of water before erecting new homes on the cheap desert land.

In June, in a sobering dose of reality, the state declared there was not enough water for all current planned construction in the Phoenix region — amounting to a 4 percent shortfall over the next century — and that all future housing developments will have to find some other source of water. Already approved projects, and new housing within Phoenix itself, could still continue, the state stressed. “We are not out of water and we will not be running out of water,” said Katie Hobbs, Arizona’s governor.

While the decision won’t halt Arizona’s growth — which has been fueled by relatively cheap housing, fine weather, and fresh jobs brought by firms such as Intel and newcomer battery manufacturers — some see the end of an era in which sprawling homes, swimming pools, lawns, and water-intensive crops could endlessly unfurl into the desert.

“It’s a clear sign that this sprawl was never sustainable and that there is just no more groundwater left to do that,” said Christopher Kuzdas, senior water program manager at Environmental Defense Fund who argues Arizona should better conserve its own groundwater before turning to new pipelines.

“We are at a real crossroads as to how Arizona grows,” he said. “There just aren’t many easy options left when it comes to water.”

For Buckeye, the conversion of farmland to new housing will subsume existing irrigation rights — agriculture takes up more than 70 percent of Arizona’s water, after all, with Hobbs recently removing state land from being used to grow alfalfa, a particularly thirsty, and controversial, crop in order to protect what she called the state’s “water future.”

Beyond that, as the city expands into virgin desert, there is water recycling, where waste water is treated and reused, or perhaps a raising of the dam on the nearby Verde River to collect more water. Any new water pipeline from further away will take many years, and billions of dollars, if it happens at all. But Orsborn insists the city will find a way.

“I’m not saying it’s not going to be a challenge, but it’s not going to break that growth,” said the mayor. “For thousands of years, water’s been moved from one point to another point. We just have to continue to do that.”

Driving around Buckeye — there isn’t really any other option to get around — can feel rather disjointed. The city’s downtown is somewhat threadbare but then at the periphery there is a frenzy of building activity, with rows of new beige and cream colored houses with piles of roof slates being put in place, swarms of machinery preparing dusty tracts of ground, flags fluttering with legends such as “new homes” and “now selling.”

Drive a further 30 minutes north into the desert, a mix of scrubland dotted with saguaro cacti and two starkly beautiful mountain outcrops, you’re somehow still in Buckeye and work is under way to conjure up a massive new development called Teravalis — meaning “land of the valley” — that calls itself a “city of the future” that will eventually house 300,000 people and various businesses.

“We are effectively building a small city,” said Heath Melton, president of the Phoenix region for the developer, the Howard Hughes Corporation. Teravalis will reclaim water and be cautious with its use of turf and irrigation, according to Melton. “We want to enrich people’s lives and be good stewards of the environment,” he said. “Buckeye is very bullish on its growth and it’s good for them to be bullish.”

For the optimists, Arizona’s past is instructive. The state has found spectacular fixes to secure the water that has catapulted its growth and is getting better at saving it — somehow Arizona uses less water than it did in the 1950s despite now having 500 percent more people.

But past conditions bear a dwindling resemblance to Arizona’s future. This summer was, globally, probably the hottest that humans have ever experienced. In Phoenix, there were a record 31 consecutive days above 100 degrees F (37 degrees C) and the seasonal monsoon season was the driest since 1895. It will only get hotter and drier. Arizona may be able to move the sea from Mexico, but somehow out-engineering the climate crisis in the longer term will be an even more grueling feat.

“I think Buckeye has some real challenges and the degree of their success will depend on the degree to which people are willing to pay for those more expensive solutions,” said Kathryn Sorensen, an expert in water policy at Arizona State University.

“But it’s absolutely feasible,” she adds. “We pave over rivers, we build sea walls, we drain swamps, we destroy wetlands, we import water supplies where they never would have otherwise gone. Humans always do outlandish things, it’s what we do.”