Oscar Sanchez’s fight against a scrapyard set to be relocated to his Southeast Chicago neighborhood has taken quite the physical toll. He’s lost about 20 pounds in the past month. He is increasingly unable to sleep, speak, or think clearly. Sometimes it’s so bad he can’t remember what he said even five minutes ago.

Sanchez knows exactly why his mind and body are deteriorating: He is one of more than 100 Chicagoans participating in a hunger strike to force the city to rethink the scrapyard’s proposed location. The metal recycling plant used to be in a wealthy, mostly white neighborhood, but its newly approved site is in a lower-income, predominantly Latino area that’s already carrying a higher environmental burden compared to other parts of the city.

“Think about somebody pulling into your home and wanting to kill or hurt those around you. You’re gonna put yourself in line, right?” said Sanchez, an organizer with Southeast Youth Alliance, a local community organization. “We’re risking our lives by just living here, of course we’re going to fight.”

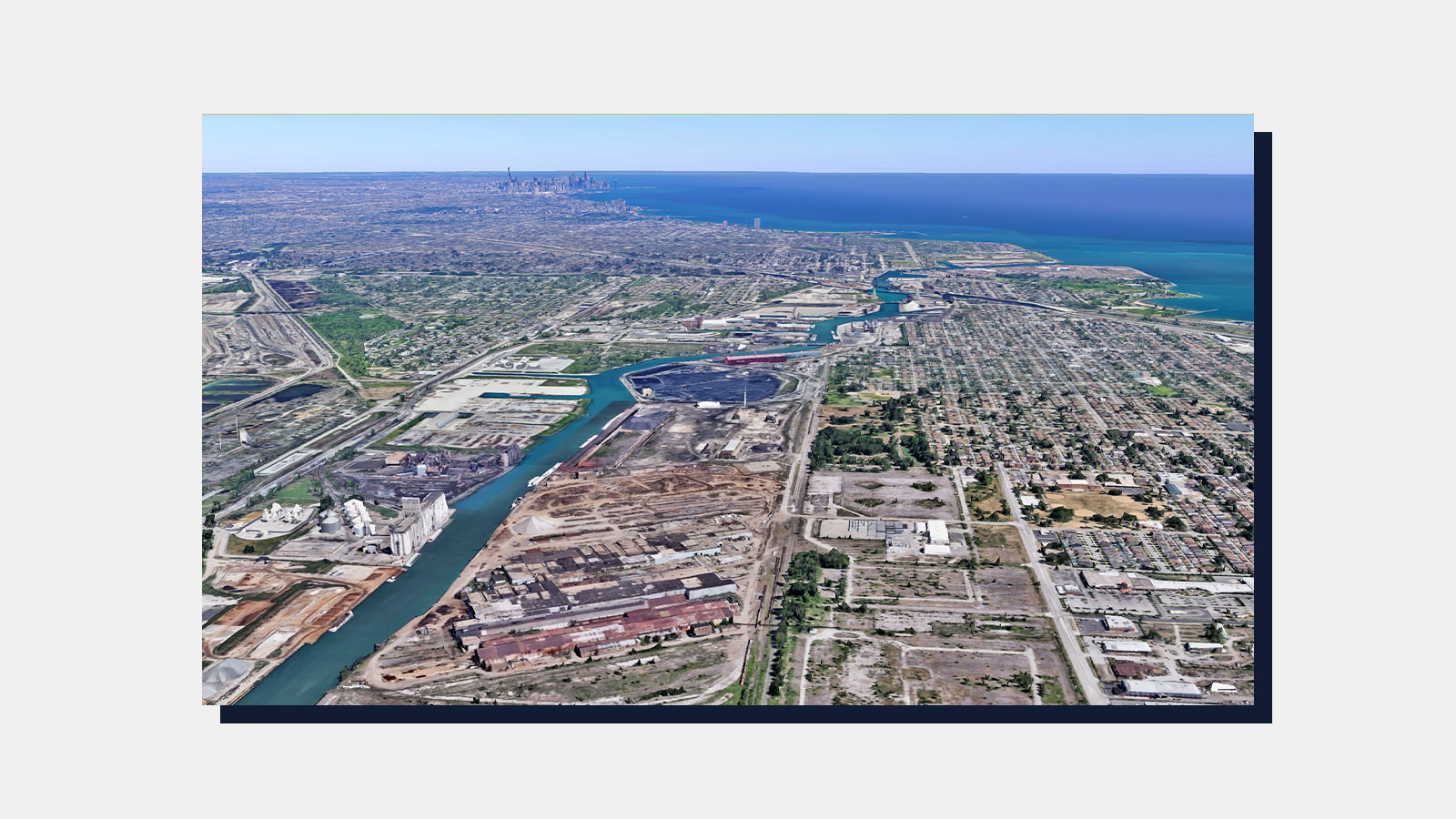

According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s EJScreen tool, which maps communities’ vulnerabilities to pollution across the country, the neighborhood surrounding the new scrapyard site is in the 95th percentile for diesel emissions, 90th for hazardous waste, and 80th for air pollution. Children living in the area are hospitalized for asthma three times more frequently than those who live near the scrapyard’s former location.

The group of hunger strikers, which has, at times, included local and state-level politicians, are forgoing food in order to call attention to how pollution from the project would add to the community’s significant public health woes. Some protesters only participated in the strike for a day or so, but Sanchez is one of a handful of community members who haven’t had a bite of food in more than three weeks. During that time, city leadership has remained silent despite the federal government opening three different investigations into the scrapyard’s move and calls from former Illinois Governor Pat Quinn to block the project’s permit.

On Tuesday, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot finally addressed the strikers. “I have heard your demand and understand that your position, and the position of the broader environmental justice movement, is for a denial of this permit,” Lightfoot said in a letter to the hunger strikers. But she added that she couldn’t commit to blocking the scrapyard’s permit and would not agree to the hunger strikers’ demand that the city place a moratorium on new permits until nearby neighborhoods reached 75 percent “herd immunity” COVID-19 immunity.

In response, the hunger strikers released a statement saying Lightfoot’s administration “would sooner let Southeast Siders starve in our hunger strike than commit to taking any real steps to address the issues.”

The city has committed to stall movement on the project until at least March 1 in order to give the federal agencies time to investigate the matter. In January, following President Joe Biden’s call to emphasize environmental justice, the Environmental Protection Agency opened an additional investigation due to the “longstanding environmental justice issues faced by the surrounding community on the Southeast Side.” Then, in early February, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Justice Department opened a joint civil rights probe into the city’s role in helping the scrapyard operator obtain a permit.

Sanchez hopes Biden’s national signaling for environmental justice will trickle down to “small, Black and brown communities across the nation.”

“This fight for the Southeast Side is a fight for Chicago and a fight for Chicago is a fight for Illinois and the nation because no one else should suffer at the hands of pollution,” he added.