In Canada’s vast boreal forest — the northern expanse of spruce, fir, pine, and tamarack trees that stretches across nearly the entire country — fire is endemic. It helps the ecosystem stay healthy. Some kinds of trees there can’t release their seeds unless exposed to high heat.

Fire becomes a problem, however, when there’s a major city in its path.

On May 3, 2016, the far northern city of Fort McMurray, Alberta, was overtaken by a massive conflagration that would become the most expensive natural disaster in Canadian history. Known among locals as “the Beast,” the Fort McMurray fire tore through the city at a shocking rate, with 300-foot-high, 1,000-degree-Fahrenheit flames that could devour an entire house in five minutes flat.

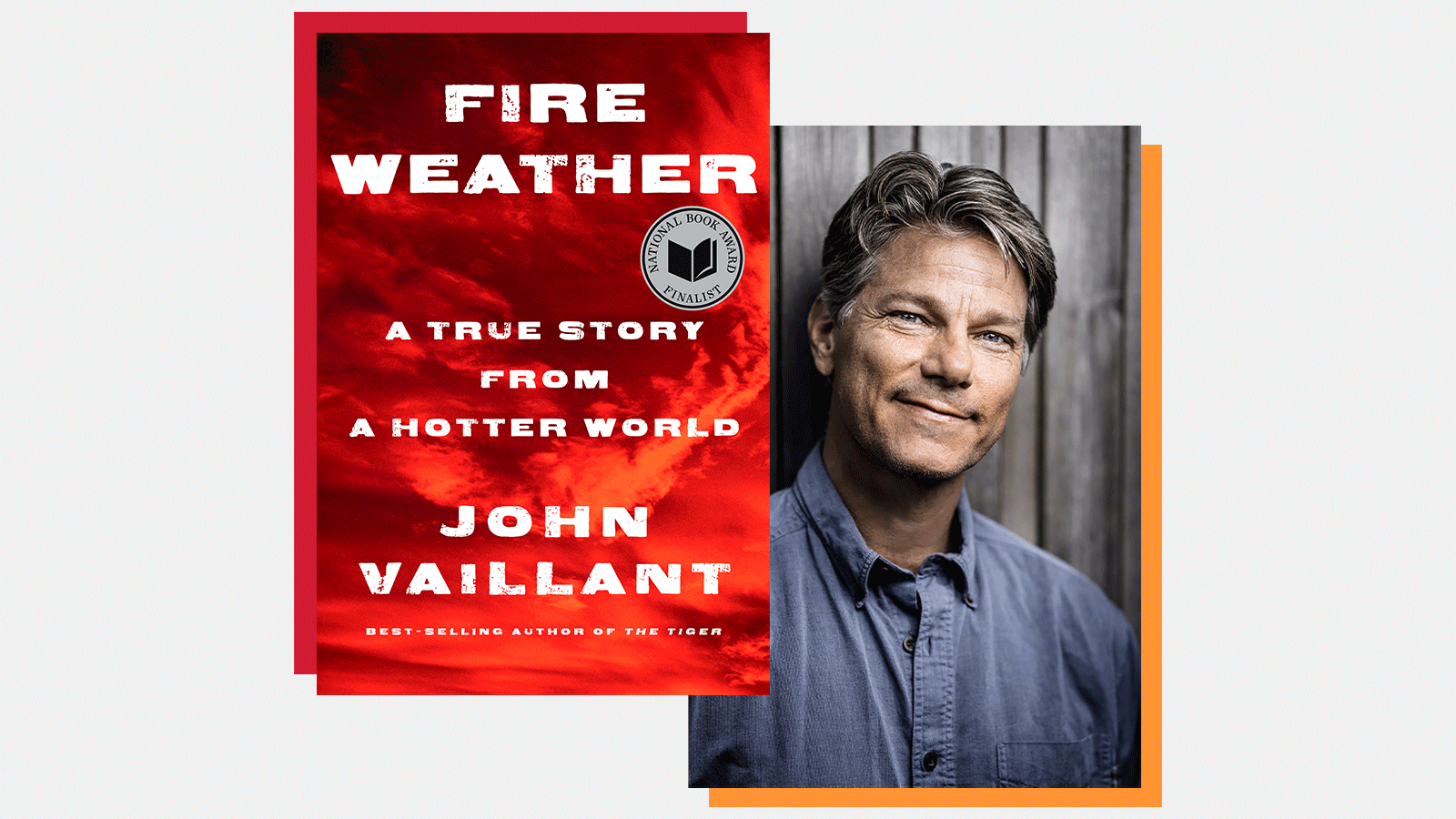

“Firefighters were not looking at houses to be saved, but as units of time to measure the fire by,” said John Vaillant, a journalist and author of the book Fire Weather: A True Story From a Hotter World. The firefighters would see one home burning and go four houses down, sacrificing the three in the middle so that they might have 20 minutes to douse the fourth in water — not necessarily sparing it, but at least slowing the fire’s progression.

This was not normal fire behavior. As Vaillant writes, the Fort McMurray fire was a climate disaster supercharged by extraordinary conditions, including Death Valley-like dryness and spring temperatures that soared into the 90s.

Fire Weather describes in harrowing detail how the Fort McMurray fire violently disrupted the status quo for the city’s 100,000 inhabitants, 90 percent of whom evacuated the city in a chaotic, last-minute scramble, in some cases with flames lapping at the wheels of their overheated cars. That no one died was “borderline miraculous,” Vaillant said.

The book, however, is not just a chronology of the Fort McMurray fire. Vaillant digs into the dark irony that a fossil fuel boomtown — Fort McMurray is one of Canada’s most important oil hubs — could be both contributing to and endangered by ever more ferocious wildfires. He also argues that residents’ struggle to process and respond to the Beast’s advancing flames is a “microcosm” of humanity’s sluggish reaction to climate change. One woman Vaillant interviewed, for example, insisted on dropping off her dry cleaning even as she saw the blaze approaching city limits.

Now, after a summer that brought Canada its worst fire season in recorded history and razed the Hawaiian city of Lahaina, Vaillant says it’s time for policymakers to do two things: better prepare for what he calls “21st-century wildfires,” the kinds of megafires that are only expected to become more commonplace as climate change progresses, and decarbonize — to prevent the fires from getting even worse.

“Metaphorically speaking,” Vaillant said, “it’s May 3 for all of us now. The fire is coming into our towns, and everybody is feeling the impacts of climate change wherever they live.”

Fire Weather is one of five finalists for the 2023 National Book Award for nonfiction; the winner will be announced next Wednesday. Grist spoke with Vaillant about his book, fire season, and humans’ persistent resistance to change — whether adapting to worsening climate disasters or challenging the entrenchment of the fossil fuel industry.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q.Tell me more about “fire weather” conditions — especially in the Canadian boreal forest. What is it about this landscape in particular that makes it so fire-prone?

A.Fire is natural in the world and has always been part of the boreal landscape. But what we’ve done by burning fossil fuels relentlessly for the past 250 years is basically supercharge the heat-retaining characteristics of the atmosphere. We’ve made these forests hotter and drier. So what we have now in Fort McMurray in May and June and July are conditions that used to be normal in Southern California — temperatures in the 90s, relative humidity down around 10 or 12 percent. That’s Death Valley dry, and it manifests as a measurable difference in fire behavior. And so now, instead of a raging wildfire that will burn itself out, you have a firestorm that generates these gigantic fire clouds called pyrocumulonimbus that are essentially stratosphere-puncturing, somewhat hurricane-like firestorms that move across the landscape. We’ve created the conditions for fire to be more rapacious, to burn more intensely and more broadly across the globe.

The radiant heat coming off the wildfire that came into Fort McMurray on May 3 was 1,000 degrees — it was hotter than Venus. Modern houses turned into gas bombs and burnt into the basement in five minutes. Firefighters have no means to fight that — what used to be a firefighting operation back in the ‘80s now is simply a life-saving operation because the fire is simply too ferocious to fight with normal means. All the firefighters can do is try to gather civilians as quickly as possible and get them out of the area.

Q.Even as the fire closed in on Fort McMurray, residents were dropping off dry cleaning, locking their doors, closing garages — can you talk about the cognitive dissonance that made people want to continue tending to their lives?

A.None of us is really ready, imaginatively, for disaster. In the case of a wildfire, I think people’s psyches and intellects are simply overwhelmed by the enormity of the flames — it’s so big and it’s so alien that you actually don’t know how to respond. And I think the default response for many people is to try to maintain their status quo.

In the case of one woman, Shandra Linder, she was just confronted with this disastrous fire — but she also had plans for that day. She had her Tuesday all planned out, and that included dropping off her dry cleaning. And so what you saw there was that gear-grinding moment when the trajectory of her day is interrupted by the immovable force and overwhelming energy of a disaster. This, in microcosm, is the difficulty that we’re having processing and responding to the implications and hazards of climate change. We’re having disasters and large fires on a regular basis, storms are more intense, the floods are worse. We’ve all read the articles and heard the stories, but we haven’t integrated it in a meaningful way. We’re still trying to drop off our dry cleaning. We’re still trying to lock our front door before we go out for the day.

Q.You also write about the irony of a fossil fuel boomtown grinding to a halt because of a wildfire driven by climate change. Can you talk a little bit about that?

A.Fort McMurray is the largest single producer of petroleum in Canada, which itself is one of the world’s largest petroleum producers. It struck me that this petroleum boomtown, with nearly 100,000 people living and working in it, would be overwhelmed by a fire that was energized by climate change. There’s this terrible irony here. We’re in this vicious cycle — this energy that’s so useful to us, that has become our status quo, is actually turning on us and making that status quo much more difficult and dangerous to maintain.

How do we break that cycle? There are certainly people in Alberta who are keenly aware of the relationship between fossil fuels and climate change. But there are also many people in Alberta and around the world who make their living in ways that are totally dependent on fossil fuels. In Alberta, the premier is an avowed climate denier and is going to do nothing to encourage a transition to renewable energy — she has actually imposed a moratorium on wind and solar installations, even as her province suffered the worst fires in its history this year and with many catastrophic fires in its recent past. They are just charging ahead, wanting to expand the development of the tar sands. It’s a feedback loop of destruction that’s eventually going to make the industry collapse.

Q.Are there any fire management or prevention lessons that you think have been learned from Fort McMurray, or that could be learned?

A.There’s a program in Canada called FireSmart that teaches how to look at your property, look at your neighborhoods, look at your community through the lens of flammability, and prepare yourself accordingly. All across California and Arizona and other flammable places, communities are figuring out how to protect their yards and porches against embers, which is the most common way houses burn. So there’s lots of local stuff you can do that doesn’t cost a lot to reduce the possibility of fire.

The other piece of this is preemptive evacuation, rather than waiting until the fire’s in your city, which is what they did in Fort McMurray. It’s becoming more common in Canada. In fact, it’s one reason we have had no civilian fatalities [this year], despite rampant fire for months and months.

So there are definitely things we can do to mitigate this, but the big-picture solution is to decarbonize. It’s really clear now what the ailment is and what the solution is.